Cool kids.

On a rainy afternoon towards the end of my fieldwork in Qilin, southwest China, I sat with one of my informants, Jiao Hua – a round, charismatic man in his 40s – to hear the story of how he ended up spending the last 25 years hooked on heroin.

“You see, it is not easy to explain now why we originally began using drugs”, Jiao Hua explained to me that day.

Jiao Hua: At the time when we started, our understanding of what we were doing was really limited. It was not like today that everybody knows that drugs are harmful, that everybody knows what their consequences are. To be honest with you, when I first began using heroin, I didn’t even fully realize that doing drugs was illegal. When we were using it we weren’t hiding. If we were on the street preparing our dose, often the police would have stopped by and would have stood there looking at what we were doing. They would have asked, “What is this thing that you are doing?” and stayed there watching us and asking questions.

Me: Really?

Jiao Hua: Really! Here, in this city, since drugs became so widespread in a matter of so little time, this happened very often. It happened even at home. You were at home with your friends and if police knew what was going on, they would have come knocking on the door. So we would have let them in and offered them a cup of tea and would have allowed them to look at us while we were preparing it, warming it up on the spoon. . .and then shooting.

A street in Qilin’s old town, where most of my interlocutors were brought up. Qilin’s old town was reportedly a key area for heroin smuggling and consumption in the city.

The story Jiao Hua recounts here is not unique, but rather resonates with numerous examples that I gathered from other long term heroin and methadone users in Qilin. Similarly to Jiao Hua, many other people I met during the 13 months I spent in the city described to me how they began using drugs amidst a general atmosphere of sympathy and curiosity.

“You see at that time, it [heroin] was a very new thing – nobody had ever seen it”, Jiao Hua would have explained me when I asked him why he thought this was the case.

“You sometimes heard about heroin, about opiates, these sorts of things, but very few people actually knew what heroin was, they didn’t even know what it looked like. So they were curious, so to speak. And this is why when they heard that there were people using drugs in the city they were rushing to come and see what opiates were, how they were supposed to be used.”

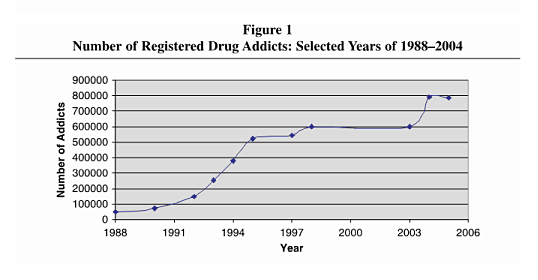

At the time of my fieldwork, some thirty years later, the situation for long-term heroin and methadone addicts like Jiao Hua had changed dramatically. Since the introduction of official regulations to control drug use in China at the end of the 1980s, addiction had rapidly moved out of the realm of exotic consumptions and started to fall instead into the category of public security issues, to be regulated via arrests and the confinement of addicts into China’s always expanding network of forced labour and forced detox centres.

In the wake of these changes a concurrent and equally radical shift occurred in the social perception of addicts, turning them from cool teenagers engaged in interesting, albeit risky, pastimes into becoming dangerous deviants whose bodies and habits had to be policed in order to preserve the health and safety of China’s population.

Set against this background, in my contribution I will go to the roots of the shift that led the sympathy Jiao Hua describes around drug use between the 1970s and the 1980s to turn into fear, social stigma and sometimes open violence against addicts. Doing so will help me adding an ethnographic perspective to the discussion we proposed in this thematic thread. As we shall see, the key factor in explaining these shifts was in fact the introduction of a legal fiction in the world of Juao Hua – the one that allowed people like him, who had previously been legally invisible, to become members of a specific legal category, i.e. the one of drug users (xishi renyuan).

A bit of context.

In order to understand fully how this happened, we need to first of all take a step back to turn for a minute to the broader context where Jiao Hua’s story took place – i.e. the county level city of Qilin. Tucked away among rice paddies and fruit plantation, close to the main route that connects Yunnan’s capital Kunming to Vietnam, at the time of my fieldwork, between 2011 and 2012, Qilin was a fast developing urban centre, with broad streets flanked by palm trees and magnolias, a gigantic government building and a multitude of shiny new and half-empty skyscrapers. Things however hadn’t always been this shiny throughout Qilin’s history.

“[When I was a kid] Qilin was nothing more than a small, backward (luohu) township”, once described to me by Yu Mi, one of my interlocutors, when talking about the context in which he grew up in the late 1970s.

“Officially, it was already a county level city (xian), however it looked much more like a small town (zhen). How shall I put, it didn’t even look like a township really, it was so backward that it actually resembled a rural village (cun).”

Accounts similar to one of Yu Mi were common to hear in Qilin. Living out of farming for most of its recent history, Qilin had in fact just recently become the centre of attention of southern Yunnan developers, mainly due to the strategic position it occupied in the centre of a vast flatland crossed by the always growing number of commercial exchanges across Southeast Asian countries.

The same roads that were now making the fortunes of Qilin had in the recent past played a key role in favouring the emergence of yet another issue that made the city famous over the years. Moving across the same routes that now brought goods and commercial deals to China, since the late 1970s a huge tide of opiates hit the streets of Qilin, allowing for people like Yu Mi and Jiao Hua to get in contact with drugs and plaguing the city with an unusually high incidence of heroin abuse – with one in 200 of its inhabitants being now reported to be a regular injecting drug user.

The massive inflow of injecting drugs in Qilin, and in southern Yunnan in general, between the 1970s and the 1980s was the end result of the wider changes that affected opiates’ trafficking routes in Southeast Asia during that period. Following the drastic relaxation of the diplomatic and commercial relationships between China and Southeast Asian countries, which followed the end of the Maoist regime, traffickers from the Golden Triangle consistently began to turn to China as a viable route for reaching the ports of Hong Kong, Shanghai and Tianjin, from where refined heroin was then shipped across the globe. Before the late 1970s, heroin had usually reached the shipping hubs of China and Hong Kong via the adventurous journeys of small Thai fishing vessel (Chin and Zhang 2007). The rising tensions among Thai and Burmese drug cartels and the launch of Thailand’s war on drugs in 1984 had however made the traditional southern route a dangerous one to run. Consequently the cargo routes leading north, toward newly opened China and India, became new favourites instead.

Such structural changes in the journeys of heroin across Southeast Asia produced a sea change in the social landscape of the cities and villages that stood close to the new trafficking routes in China, as they made long-gone protagonists like opium and its derivatives – heroin and morphine – to reappear in the country. By turning opiates into markers of a bourgeois lifestyle since the beginning of Mao’s regime, the Communists had in fact been successful in the previously unthinkable enterprise of wiping opium and its derivatives out of China. Often emphatically celebrated as the only effective war on drug ever undertaken in the world, Mao’s campaign combined police repression, border controls, propaganda and grassroots mobilization and produced the indisputable result of drastically reducing the availability of opiates in the country, making their use to remain confined to a restricted group of users. In the wake of these facts,

a thunderous silence descended on issues related to drugs, fitting for a problem deemed to no longer exist in the country.

It is to the enduring silence produced by Mao’s war on drugs that we now need to turn in order to explain the curiosity around drugs Jiao Hua describes in the bit of interview reported at the beginning of this article. This is even more so as it is to this very silence that Jiao Hua, and many others among my interlocutors in Qilin, kept on going back in order to explain why they started using drugs in the first place.

“You see”, told me Jiao Hua in this regard, “at that time I was just stupid, I didn’t understand anything. How can I say it? I didn’t just start because friends made me do it. I started because at that time my knowledge about drugs was really not enough (bu gou)”.

Albeit, as I have described elsewhere (Zoccatelli 2014), things were probably a bit more complex than this – calling into question issues like the frustrated consumerism in the country’s most remote borderlands, the increased individualism of China’s youth and the weakening of the traditional social circles of family and work units – the lack of a public discourse around drugs is indeed to be accounted among the key factors that led thousand of teenagers in China’s borderlands to turn to injecting drugs between the 1970s and the 1980s. But not just that. Silence and the widespread perception of drug use as a problem that no longer existed are also at the bottom of the stunning lack of official regulations around drug use, which characterized the first decade of newly reformed China. Specific official attempts to legally regulate drug trafficking, smuggling and consumption in China were in fact only enforced starting at the beginning of the 1990s. A brief account of how these regulations came to be implemented is helpful here in order to understand the shift that led young people using heroin to turn in the public imagination from cool teenagers into dangerous outlaws.

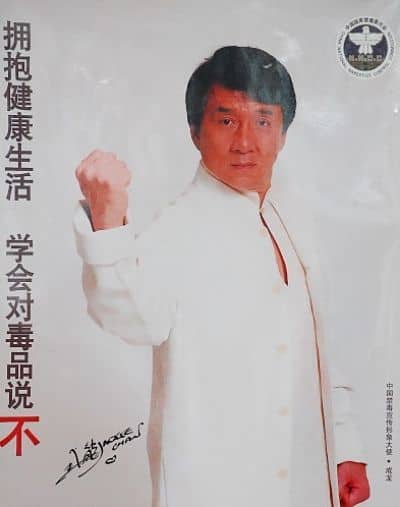

In today’s China, things are quite different from how they were at the time when most of my interlocutors began using heroin, between the 1970s and the 1980s. Posters encouraging people to stay away from drugs were ubiquitous in Yunnan at the time of my fieldwork. In the one reported above, kung-fu movie star Jackie Chan urges his fans to “Protect life and health, learn to say no to drugs”.

Outlaws.

When one looks at the sequence of events that led China to adopt official measures to regulate drug use in the country, one key fact becomes immediately noticeable: how their implementation was deeply entwined with the concurrent emergence of another pressing public health issue – the outbreak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the country. In 1985, China’s public health authorities disclosed the news that a first AIDS-related death had been registered in the country. Following this news, health authorities established the implementation of a series of public health controls in areas and among people deemed to be at risk of contagion, in order to be able to scientifically locate possible hotbeds of the epidemic. In 1989, a round of tests among local injecting drug users came back wit the result that 146 people had been found to be HIV positive in the border town of Ruili.

The news of Ruili’s contagions proved critical in radically transforming China’s public discourse around AIDS. Up to that moment, China’s authorities had in fact treated AIDS exclusively as a disease of foreigners – or “capitalism-loving people” (爱资病aizibing), following a wordplay widely used in the Chinese media, which punned the almost identical-sounding scientific name of HIV/AIDS (艾滋病aizibing). The news that HIV/AIDS had instead already started to spread among China’s citizens led the country’s authorities to turn their attention from the outside of the nation to its inside. Whereas before selective visa releases and controls on national borders had been the key interventions enforced to keep AIDS under control in the country, after Ruili, the new priority of China’s government became that of drawing new – this time internal – borders around the epidemiological sub-groups considered to be most at risk of contagion. This with the aim of keeping them, and the risks they bore, isolated from the healthy part of China’s population. Among the groups addressed by this new set of measures was the constantly growing number of people who since the previous decade had started turning to heroin in the country.

The new attention that rose around the public health risks related to drugs caused the until then almost entirely unregulated sub-group of people with a history of drug use to become the objects of a growing number of technical and legal interventions. First reified into members of the epidemiological category of Injecting Drug Users (IDUs), people like Jiao Hua and Yu Mi ended up becoming full-blown legal personas at the beginning of the 1990s, when the government launched what it defined as China’s new “battle against drugs”. As part of these initiatives, in 1990, China enforced the “Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on the Prohibition against Narcotic Drugs”, which banned the sale, smuggling, possession and use of narcotics. The Decision for the first time addressed people using drugs as part of a specific legal category – indeed, the one of “people who use drugs” (xishi renyuan) – and established the need to deal with them through the use of corrective measures, mainly implying their confinement in forced detox centres (jiedusuo) for a period of up to 2 years and in forced labour camps (laojiao) for 3 years, in the case they were caught relapsing.

Marginals.

The consequences of these new legal interventions were still very noticeable during my fieldwork. Besides populating the world of addicts with new, invasive technologies to regulate their lives and behaviours, the fact of being turned into members of a specific legal category also contributed to produce some subtler and less immediately visible changes in their lives. Among these, a key place is occupied by the radical shift in the social perception about them.

Linking addicts directly to the spread of widely feared diseases like AIDS and stressing on the need to control what were now deemed to be publicly dangerous movements and behaviours, had in fact the result of making the joyful atmosphere of curiosity and coolness that Jiao Hua described around his initial approach to heroin to fade away and to leave space instead to fear and moral contempt for drug users’ lives.

The social stigma that ensued from these changes has been long lasting and its effects remained tangible in my fieldsite. Almost everyone among my interlocutors in Qilin was unemployed, reporting to have lost their job and to be incapacitated to find a new one as a consequence of the regulation that requires the lettering “xishi renyuan” (i.e. person who uses drugs) to appear on the ID of all the people caught at least once under the effects of drugs. As the lettering is permanent, and cannot be deleted even after years a person had stopped using drugs, unemployment related to social stigma was also prominent among people who reported having quit heroin and were now only enrolled in the government sponsored methadone treatment program. The only rare exceptions I encountered were among people working in lower paid jobs, like rubbish collection and small-scale transportation. Social discrimination was even graver in other fields of life. Stories about denied access to healthcare for instance abounded in my fieldsite and were mirrored by the data emerged from large-scale quantitative surveys, which denounce how social stigma and discrimination are still “highly prevalent among the public, including among many health-care professionals” (Han et al 2010: 47). As a way of conclusion it is thus worth reporting here one of these stories, the one that Gu Bao, a woman in her late 30s, told me one day when I met her by chance while she was seeking treatment for one of her fingers, which as a consequence of heroin injecting had started to become gangrenous.

“When normal people get sick, they just go to hospitals and get treated”, Gu Bao told me that day.

“[…] But not us. Especially with these blisters, no one in the hospital wants to help. Because they immediately understand you are a drug user and they know we probably have AIDS. It doesn’t matter if you go with your parents; it doesn’t matter if you offer to pay a lot for it. I did it all, but they just turned me away. When you are one of us it’s like this. People first are disgusted by you. Then disgust turns into fear. And then fear turns into hatred”.

Conclusions.

The words of Gu Bao are useful to take us back to where we started, as they are a lived testimony of the power of legal fictions to transform the lives of the people they address. At the beginning of this thematic thread we described legal fictions – and the new social categories they create – as metaphoric infrastructures (Ricoeur 1975; Elyachar 2010) that allow for the world to be made legible and for certain aspects of it to become more easily manageable. The introduction of legal measures to deal with drugs in China did precisely this – they allowed to inscribe the risks related to HIV/AIDS into a newly created category of people and to make possible the management of the epidemic through the control of their bodies, behaviours and movements. The stories of Gu Bao and Jiao Hua, among others, are concrete examples of the grassroots and long-term impact of these regulatory acts. They show how, once they get routinized, legal fictions turn into much more than functional metaphors to deal with technical issues. Instead, they become full-blown truths that dictate how people live and interact.

Works cited.

Chin, K.-L. And Zhang, S.X. 2007. “The Chinese Connection: Cross-Border Drug Trafficking Between Myanmar And China”. Final Report To The United States Department Of Justice (Unpublished), National Criminal Justice Reference Service.

Elyachar, Julia, 2010. Phatic labor, infrastructure, and the question of empowerment in Cairo. American Ethnologist 37(3): 452–464.

Han, M., Chen, Q., Hao, Y., Hu, Y., Wang, D., Gao, Y., Bulterys, M., 2010. Design And Implementation Of A China Comprehensive AIDS Response Programme (China CARES), 2003-08. International Journal Of Epidemiology 39, Ii47–Ii55. Doi:10.1093/Ije/Dyq212

Hong, L. And Bin, L. 2008. “Legal Responses To Trafficking In Narcotics And Other Narcotic Offenses In China”. International Criminal Justice Review 18 (2): 212-228.

Ricœur, Paul. 1975. La métaphore Vive. Paris: Le Seuil.

Zoccatelli, G., 2014. “It Was Fun, It Was Dangerous”: Heroin, Young Urbanities And Opening Reforms In China’s Borderlands. Int. J. Drug Policy 25, 762–768. Doi:10.1016/J.Drugpo.2014.06.004

Featured image (cropped) by Danielle Spraggs (flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)