Let me begin this second part of my non-linear surveying of digital ethnographies by quoting the anthropologist Tom Boellstorff once more. Along with him, I do also have difficulties with ‘identifying the analytical work that digital is supposed to accomplish’ (2008: 18) in common parlance. When I say that Peng is a digital ethnography then, I mean two specific things.

On the one hand, the game is a fieldwork-enabled computational artefact that aspires to deliver situated insights into the largest peacetime movement of people in history: China’s four decades of continuous internal migration.

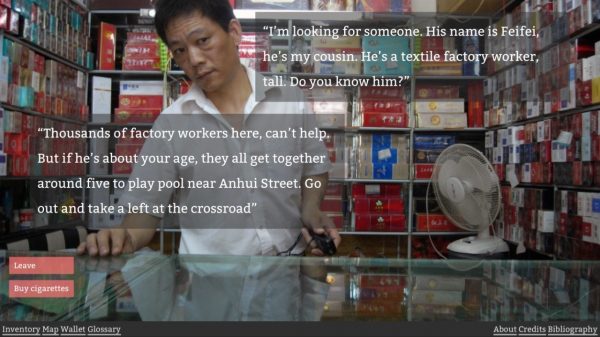

The game’s non-linear narrative weaves together the notes of my own ethnographic diary with actually-recorded fieldwork conversations between Peng and his own relatives, friends and colleagues to enfold the player in a contextually rich “view-from-somewhere” on Chinese migration.

Similar to any ethnographic monograph, the game balances this point-of-view perspective with parallel accounts of Chinese migrations found in the scholarly literature. But differently from classical nonfiction narrative, the way it achieves generalisability and ultimately relevance is virtual rather than referential. The nonfictional character named Peng is given the opportunity to fictionally meet other nonfictional fieldwork participants from the specialist scholarship on urban and migrant China, so that more than one single perspective on migration can be addressed in the game. The game makes a point of blurring the line between fiction, non-fiction and ethnography to complicate the various hierarchies of ethnographic storytelling as well as the unidirectional framing usually entrapping the mainstream narrative on migration. In doing so, it does also raise the critical question of how, as Elizabeth Enslin puts it, we should go about engaging ‘audiences who need to hear about the people we study’.

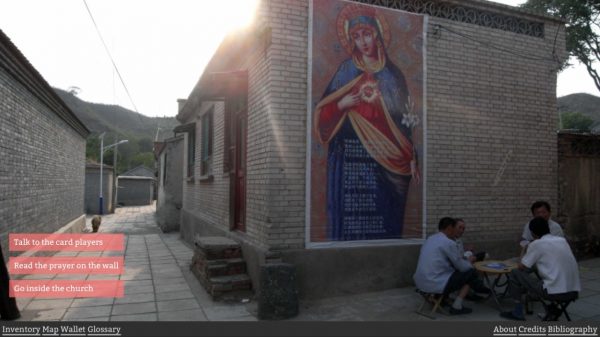

The computational mechanisms of Peng’s gameplay involve a multi-choice taskbar, which is every bit the by-product of my childhood proclivity for fantasy literature as it is of fieldwork methodologies: I spent several months of my stay in Lingshui asking Peng hypothetical questions about his future as we waited together for the day of his eventual departure to Beijing. These mechanisms strive to produce what the game theorist Ian Bogost’s calls ‘procedural rhetoric’ (2007). ‘Procedural rhetoric’ is the capacity that videogames have of mounting an argument about how social and material practices do, could or should work in real life by compelling players to take consequential choices in relation to their virtual unfolding. (If you are intrigued by this, go to 3 now.) By making choices for/with Peng, the player is made to reflect on the analytical opportunity to study migration outside the usual economistic binarism of push and pull factors, and within the ethnographically more accurate register of instability, incompleteness and serendipity, qualities that ordinarily beset any migratory choice in real life.

That is, Peng is both a classical ethnographic account of the migratory experience of a Northern Chinese young man as well as a social scientific argument in support of person-centred analyses of migratory processes. In the latter sense, Peng’s interactive gameplay is meant to persuade the player that to better understand migration as a social phenomenon one has to ask oneself, and take a stance on, those very ethically-fraught questions about subjectivity, mobility, belonging and marginality that every migrant grapples with in their daily life. In a way, this type of ‘ethnographic interactivity’ operationalizes an argument first advanced by the machine-learning theorist Jimmy Lin (2015) that the use of digital artefacts in the social sciences ought not to be predicated on their ability to deliver ‘better science’, but rather ‘better engineering’: making our arguments and truth claims about social process less aloof and more relatable to our potentially very different publics.

If you are wondering about who these publics can be, head to 2.

If you want to reassure yourself that Peng is not the harbinger of some new form of digital exploitation, go to 3.

2. Neo-reaction and Twineries

Peng was developed, with the assistance of the creative coder Tom Chambers from Random Quarks, on the open-source, web-page builder tool Twine. For those among you who are not well versed in any programming languages (I am one of you!), nor seem to hold so strong an appetite to learn any, the engrossing thing about Twine is that it does not require any proficiency in coding to be taken up. For the digital ethnography Peng, creative coding was indeed sought after to include game-like mechanisms such as a toolbar, a glossary and dealing with its complex visuals. But here or here you can find equally interesting examples of thought-provoking, twine-based games which I believe engage the player along similar lines to Peng. Though, as I’m not in the business of scaring anyone off with technicalities, let me turn to an apparently minor aspect of entry-level coding tools such as Twine which will be certainly more relevant to the ALLEGRA reader.

The reason why Twine should matter to the only cursorily digitally engaged reader is its short-lived, amusingly twisted and poorly digested appearance as an object of (Euro-American) contentious politics around 2014-15. This is the toxic yarn of gender harassment that goes under the name of Gamergate (Mortensen 2018). I will spare you most of the dumbing details of what in hindsight represents the ‘coming-out’ moment of the systematic form of online trolling now championed by the American alt-right, whose aggressive online tactics have been recently credited for the noticeable tilting of the Euro-American political compass to the far-right (Nagle 2017). This one drama plays out in four acts: 1. Twine is made popular by the videogame designer Anna Anthropy who, in a widely-acclaimed book about the emerging counter-cultures of the gaming industry (2012), had prized the platform for lowering the coding barriers to entry in the business. 2. The sense of first-person identification that Twine games offered resonated with traditionally marginalized groups whose efforts to either raise awareness of (and perhaps change) their status as marginalized could benefit from the platform 3. Zoe Quinn, a feminist video game programmer and artist, publishes her Twine-based interactive narrative on depression called Depression Quest. 4. A flurry of hateful online assaults, including rape and death threats, is directed against Quinn and other female video game critics, who are variously accused of infidelity, opportunism and of needlessly politicizing what should remain mere entertainment. 5. Milo Yiannopoulos weighs in on Breitbart. I should stop here.

In a long New York Time Magazine article dedicated to progressive voices in the videogame industry, Laura Hudson has summarised Quinn’s online slandering ‘as a battle over not just entertainment but identity: who gets to be called a gamer, what gets to be called a game and who gets to decide’. As Grace Converse puts it, ‘hypertext narratives allow participants to engage experimentally in alternative realities, subjectivities or behaviours. Hypertext users may experience new kinds of freedoms and new kinds of consequences’. Because they ultimately broaden one’s cultural horizon and change cultural demands for what can be consumed through gaming, interactives games – it has been argued – are loathed by a corporate gaming industry that design video games to be formulaic, status-quo preserving and riskless.

Much more so than in traditional academic publishing, videogaming is becoming a vehemently contested terrain for today’s increasingly digitalised political cultures. And perhaps, this is the one place where the question of the democratisation of the means of cultural production can be addressed in the most consequential ways.

In this respect, Twine’s ease of use, creation, sharing, and participation, offers a vantage point for those among us who believe in the wider relevance of anthropology as a contributor to public debate (Harvey 2014). Digital ethnographies like Peng may contribute to diversify the cultural offer of online gaming and expand the imaginative resources and endpoints of online journalism too.

If you wish to know more about students’ reaction to playing the Peng game, go back to Part I

target=

If you are asking yourself what real-life Peng may think of all of this, head to 4.

3. Ethics

The Peng game incorporates interactive choices that are designed to directly interrogate students’ ethical reasoning. As explored by an emerging body of work on digital ethnographies – and as we have discovered by introducing the game to students – the immersive gaming environment allows for novel forms of apprehension of ethnographic knowledge. Following Roland Barthes (1980), videogames work similarly to photography in explaining content through context while demanding self-identification. In videogames though, it is the interactive context that forces player to identify with the storyline proposed. Importantly, this unstable environment interrogates not just players’ comprehension but their very own ethical agency and interpretative capacities. How would a Chinese male migrant behave in this situation? Should I send remittances home or keep them to myself? Should I comply with laws and register to the local police station even if this exposes me to unfathomable dangers? What about involving oneself with union politics? In this light, videogames place students in a so called “ethical gym” (Bittanti 2005) where seemingly ethical or un-ethical choices are experienced as separated from their consequences.

Conversations in class have often revolved around what type of “Chinese son” Peng really is and how he could survive the many obligations his family and friends are putting on him. Interestingly, students seemed to be going through some kind of internal conflict when, on the very last class of term, I asked them to use their own understanding of the Peng game to discuss recent public statements made in China about the need of democratic reforms in the country. Would Peng benefit from living in a more democratic China? To ask this question, students had to triangulate between what they had been learning about China during many months of teaching (that China has its own axe to grind when approaching the question of democracy), from the Peng game (that whatever the regime in force, Chinese migrants are usually at the losing end of reforms) and their own personal feelings about that question (that democracy is largely a good thing) to come up with a principled argument in support or against the afore-mentioned statements. That is, the game provided involving if largely ambivalent ethical counterpoints to what students had been learning throughout the module, thus pushing them to reflect on social change in China on more nuanced, less abstract terms.

If you feel you have missed too much of what came before, go back to Part I

4. Reflexivity

And then of course there is the question of my own ethical standards for even considering turning someone else’s life into a ‘game’ for pedagogical purposes. While consent for this project has been gathered from a selected number of individuals at various stages of the collection, designing and implementation process, not all the characters that appear in Peng do in fact know that their likeness has been captured and computed in an open-access videogame. Anonymisation in the game cuts both ways, names do not correspond to real people just as individual appearances do not always match their real-life owners. But evidently this is a long shot from declaring that the people who are made to inhabit my game have been thoroughly and exhaustively advised on the potential implications of digitalisation, mostly because I do not know what these may be either. For my friend ‘Peng’, a hardcore MMORPG player himself, things are slightly different. Last time he checked from China, the game could only be played with a VPN. But for the few times he managed, he thought it was good fun. Some of the endings he’d have actually preferred over how real life ultimately played out for him and his family. Speaking of which, he has recently tried to convince me to turn Peng into an advergame for promoting rural tourism to his home village and the surroundings. The next interactive indie game I’m planning to discuss with him received sensational reviews in China, and you can play it here.

Feeling like playing Peng? Click here.

Else, this is the end – game over – for now.

Bibliography

Anthropy, Anna 2012. Rise of the Videogame Zinesters. Seven Stories Press.

Barthes, Roland. 1980. Camera Lucida. Hills&Wang.

Matteo Bittanti (ed.) 2005. Gli strumenti del videogiocare, Milano: costa & nolan.

Boellstorff, Tom 2008. Coming of Age in Second Life. An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton University Press.

Bogost, Ian. 2007. Persuasive Games. MIT Press.

Harvey, Alison 2014. Twine’s revolution: Democratization, depoliticization, and the queering of game design, Game 3: 95-107.

Lin, Jimmy 2015. On Building Better Mousetraps and Understanding the Human Condition: Reflections on Big Data in the Social Sciences, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 659(1): 33-47

Mortensen, Torill Elvira 2018. Anger, Fear, and Games: The Long Event of #GamerGate, Games and Culture 13(8): 787-806.

Nagle, Angela 2017. Kill All Normies: Online culture wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the alt-right. Zero Books.

Sandifer, Elizabeth 2017. Neoreaction a Basilisk: Essays on and Around the Alt-Right. Eroditorum Press.

Featured image by Fabian Grohs on Unsplash