I’ll start with the most embarrassingly candid disclosure one could possibly make in the context of this thematic week: I am not such a big fan of videogames myself. Most of what I know and appreciate about gaming was imparted to me by my older brother – he truly is the reputable gamer in the family, topping the online European Street Fighter ranking for a while around 2010 – and by a childhood spent among systematically absent, hardworking parents. True, my adolescence did reek of torpid late spring afternoons spent leafing through some Choose your Own Adventure playbook or stuck into the convoluted plots of the latest point-and-click videogame. And yes, one of the origin stories I recently started telling myself about my interest for ethnographic fieldwork harks back to the supposedly pivotal encounter I had in my teen years with Dungeons & Dragons and role-playing in general – a fantasy world filled with alien languages, exotic magical rituals and conflicting ethical codes you either master or end up being subjugated by.

But surely enough, that very white-male-adolescent effervescence I basked in while playing fantasy games was soon to evaporate in contact with the systematic study of actually-existing cultural differences, and their imbrication in regimes of political oppression and exploitation.

In a way, my induction to anthropology was also the moment this comforting relationship with (video)games, and the creatures they are inhabited by, suddenly broke down.

For instance, how could I keep figuratively hanging out with the elven-kind, a people who now appears as entirely composed of undatable racist snobs? And to be clear, the disingenuous levity of this rhetorical question is here only to shelter you from the more ‘hardcore’ ethical complicities that the game-entertainment industry and its accompanying racialised economies ultimately depend on: from the slave labour undergirding the ‘improvised’ Congolese coltan mining sector (Mantz 2008), to the ‘docile and dexterous’ Navajo women weaponised by Silicon Valley’s semiconductor manufacturers (Nakamura 2014), from the recent spate of suicides among China young electronics workers (Pun et al. 2016), to the misogynist, neo-reactionary subcultures infesting and policing the ludic boundaries of Euro-American online gaming (Sandifer 2017).

Yet, despite the pervasive structural and symbolic violence coiling around the global digital industry, there’s something about videogaming that always stayed with me. Think of the ways in which games can be intellectually stimulating, how they could ‘encourage players to think in terms of relationships, not isolated events of facts’ (Gee 2008). How they ‘sharpen […] critical thinking competencies’ (Faeber 2015), or ‘force players to inhabit’ particular ‘political ideologies’ (Anthropy 2012). It could be argued that to truly appreciate gaming one needs first to stop bracketing out the harrowing circumstances of videogame production and consumption – to paraphrase Donna Haraway, one should ‘stay with the trouble’ – and begin playing videogames ‘critically’ (Flanagan 2009).

That is, I am here assuming a sceptical audience and still suggest that videogames can appear ‘good to play with’ if explored along the discursive tension generated in the friction between their disquieting origins and escapists intentions and the opportunities of self-transformation that their mechanisms arguably ‘afford’ to players (Cardona-Rivera, Young 2013; Knox, Walford 2016). With this ALLEGRA thematic-week we propose a fair-minded rapprochement to an otherwise inappropriately belittled conversation – but one with an important pedigree in the social sciences (i.e. Huizinga 1949, Vygotsky 1978) – between gaming, anthropology, politics and teaching, to generate insights into the increasingly relevant question of what kind of relationships do and might as well exist between games and those who play them (Spencer 2018).

Following Tom Boellstorff (2006), we will begin our investigation by positing that anthropological theory and methodologies have a lot to offer to the study of (video)games.

But rather than considering videogames as an objet trouvé for anthropologists, I will take the less explored route of proposing videogames as one of the potential products of ethnographic research itself.

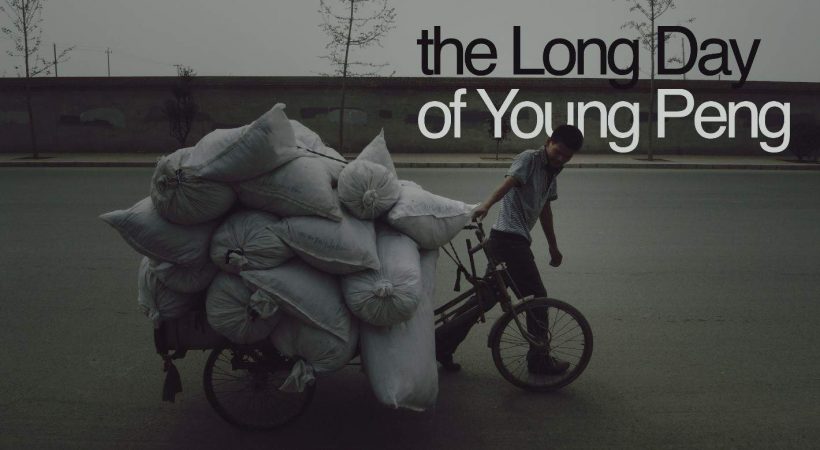

To do so, in what follows I will plunge into the experience of researching, designing, writing and implementing a concrete digital ethnographic piece into class teaching – experience which constituted a good slice of my pedagogical effort for the last couple of years. The anthropological/educational game I will ask you to wrap your heads around is called The Long Day of Young Peng, and it has been designed, among others, by the author of this text.

This is a two parts introduction to an Allegra thematic week that does not follow received editorial conventions. In the footsteps of the indie videogame designer Anna Anthropy (2015), and as a homage to my beloved Fighting Fantasy books, I am organising this short essay around a choice-rich reading structure. Therefore, in what follows you will be asked to make a choice. What you choose will determine the order and the subject explored by this piece.

And so it begins:

To engage with the main focus of this thematic week, scroll down to 1 and continue following instructions.

If you are into teaching and want to jump straight to the pedagogy of videogames, go to 2 and do as advised there.

To disregard the non-linearity of this text (and spoil yourself the fun), simply continue reading and ignore instructions.

- The Game

Tom Boellstorff opens his mesmerizing ethnographic journey into the online virtual world of Second Life (2011: 3) with a homage to Malinowski’s famous opening in The Argonauts. I am compelled to engage in a similar ludically altered allegory here:

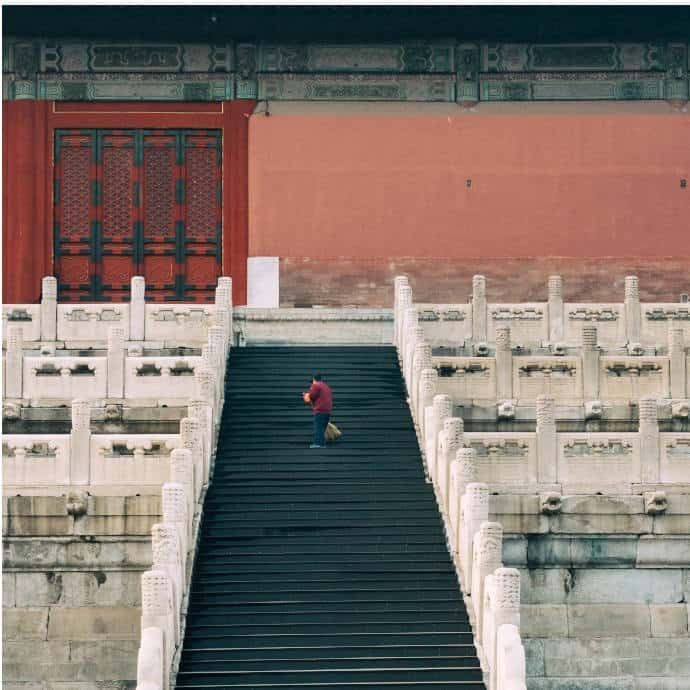

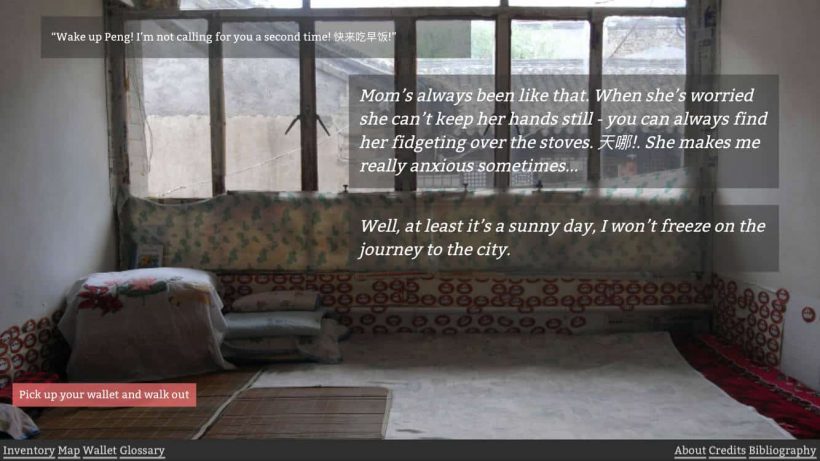

Imagine yourself suddenly set down surrounded by your few properties, alone in the corner of an unfinished spare room of a traditional North-China rural house while your mother’s weakening shouts bring you the notion that the long-delayed day of your departure is finally here. You have nothing to do, but to start at once what may be your last day home for a while. Imagine further that you are an under-age migrant, without previous experience of urban life, with nothing to guide you and only few people to help you.

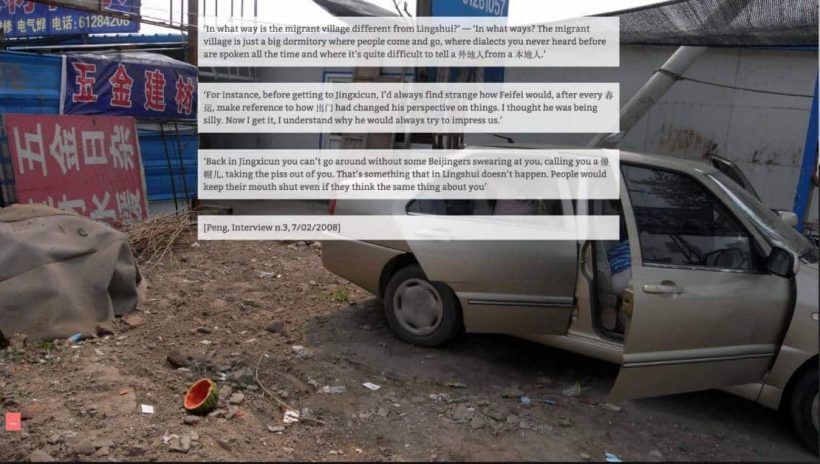

This exactly describes the beginning of the digital ethnography The Long Day of Young Peng. But it also closely approximate how Peng – here a fictional name given to a real-life friend from my 2007-09 fieldwork in North China – had decided to colour, in both off- and online conversations with me over the years, the story of his first journey to Beijing.

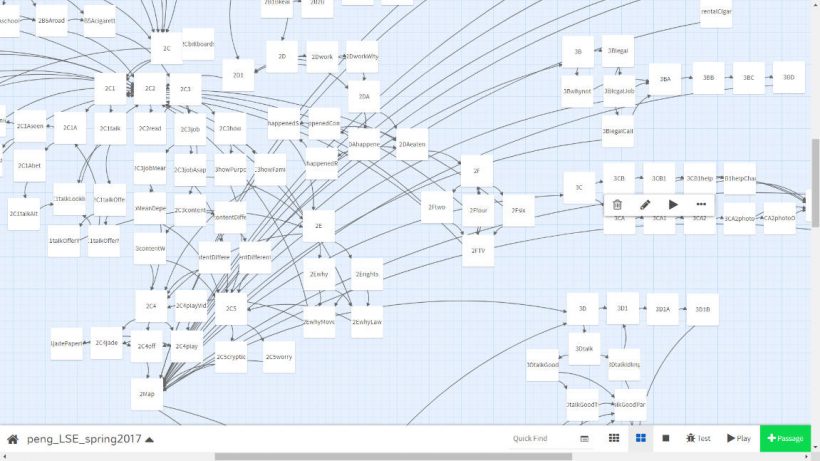

The Long Day of Young Peng is a nonlinear, interactive HTML encoded storyline that uses original ethnographic material (fieldnotes, excerpts from interviews, pictures, videos) to chronicle one day in the life of Peng, a young Chinese migrant (if you are curious about the technical wizardry that makes this possible jump to 3 now). In this digital ethnography, the player is put in Peng’s shoes on his journey from his native village to Beijing in search of employment. As in the text you are reading right now, the game is based on a multiple-choice mechanism. Through interacting with other characters, the player relives Peng’s first day in Beijing as well as familiarising themselves with topics in the study of contemporary Chinese society.

The player makes choices throughout the game that will determine the places, people and ethnographic themes Peng will eventually encounter.

Throughout the game, the player collects items, money and keywords that could be used to unlock further content in the game as well as provide more detailed analysis of the ethnographic material. The game also includes a bibliography, as some of the topics the digital ethnography touches upon are elucidated through ethnographic examples taken from the anthropological literature on China and scripted into the game. The game ends in diverging ways – none of which reflects what really happened to the real person named Peng, but which nonetheless reproduces some of the most likely outcomes of second-generation migratory projects in China (Sun 2014) – depending on the cumulative effects of the choices made throughout it.

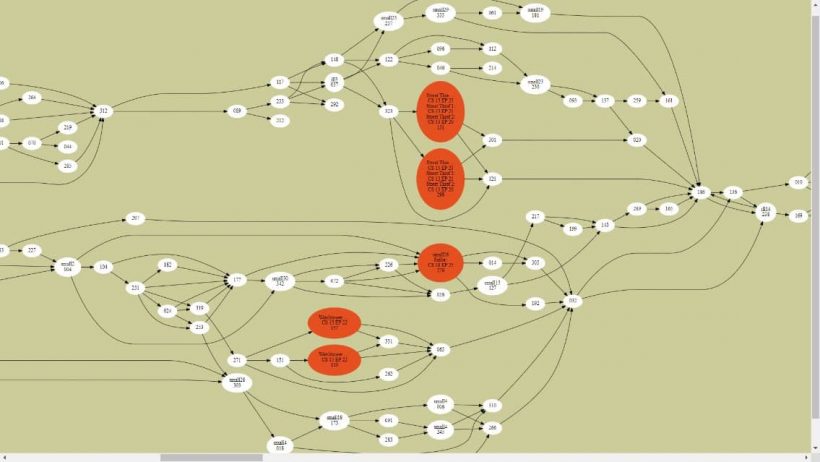

Busy interactive pathways in Peng (from Twinery.org) and the interactive book Lone Wolf (from Projectaon.org)

The idea of developing a digital ethnography came in response to a 2016 LSE Learning and Technology grant to support large-scale, technology-informed initiatives with the potential to have a substantial and lasting impact on teaching practices around the School. This call reasoned along similar lines as a previous attempt at digitalizing ethnographic material that I had been toying with in previous years. The ethnographic material on which the Peng game is based has been collected during eight months of fieldwork in Lingshui village, Beijing Municipality, People’s Republic of China, as part of my first MA ethnographic project on the nexus between environmental degradation, rural-to-urban migration and marginality in rural China (Pia 2016). That piece of research was subsequently extended in the summer of 2009 period during which the media artist and digital curator Marco De Mutiis and I visited Lingshui together to record a new set of interviews and videos and produce extra photographic material. Of great inspiration for this second period of ethnographic work was the then single most influential interactive journalism piece to be published online, Voyage au bout du charbon, produced by the French newspaper Le Monde. In 2010, we put together a proposal to pitch our original web-documentary project to the Sheffield Doc-Fest, an international documentary festival and marketplace, but failed to seize enough funding. The project was then put on hold for several years awaiting new funding opportunities.

At this point in the text, you could either jump to the practicalities of how the Peng game was introduced into class teaching by scrolling down to 3 or you could click here and play the digital ethnography yourself, until at least Peng’s final departure from Lingshui. Once you are done, come back to this page and read 2.

As you make your way through Peng’s last day in the village, try to fit into his shoes and think carefully to what he/you shall do. However, as you move further into the digital ethnography, do not forget to cast a critical eye on the ways in which the game addresses you.

What does interactivity do to our ethnographic accounts? How is the storytelling of anthropology challenged or transformed by this media form? And what about the ‘truth claims’ (Rutherford 2012) we advance through our ethnographic findings?

To paraphrase a recent curated collection by Darren Byler and Shannon Iverson on the relationship between fiction and nonfiction narratives in anthropology: ‘what is the work the interactive stories do?’

- Pedagogy

There’s a growing amount of evidence (Blank 1985; Gee 2005; Squire, Jenkins 2003; Squire 2005; Kardan 2006) suggesting that the role-playing afforded by gaming tools often translates into the ability of challenging one’s own default assumptions and enhances a more flexible and unorthodox appreciation of complex social phenomena. All these outcomes, you will agree, represent highly sought-after goals in the teaching of the social sciences. But this begs one further question: how can games possibly be educational? The Peng game, as all interactive simulations, provides students with an alternative virtual sensorium that is rich of learning cues. In the constructivist approach to learning (Vygotsky 1934; Laurillard 2002), much is made of the notion that knowledge is assembled out of a given context by the purpose-driven cognition of the active learner. While all contexts are potentially conducive to some form of learning, some contexts may be explicitly designed to be saturated by teaching affordances, i.e., learning opportunities embedded in an environment to support teaching activities. The Peng game is one such context.

The game is replete with cues pointing to salient facts about contemporary China, which are made explicit subjects of analysis in course lectures and readings. For example, one picture could show the inside of a rural house plastered with propaganda posters of Mao Zedong. While the interactive text may not directly pick up on the visual content of the background environment, the player may still find it compelling, or be reminded of relevant discussions in some of the course’s readings or lectures.

At a different moment in the game the player may be left wondering why some of the characters Peng meets seem to treat him badly or dismissively, without the game giving much explanations as to the underlying reasons for such behaviours.

A case in point is the derogatory language that urbanites resort to when dealing with rural migrants.

When playing through these scenarios, students have often been able to pick up on such cues. From there, they would usually move to question their peers or me as to the reasons behind such content or behaviour. In class, students often commented that the game “is very deep” and that they enjoyed the challenge of reading between the game’s lines. When briefed on the reasons behind the choice of introducing teaching affordances into the game, students were also reminded that deep reading was a skill that students were also supposed to be employing when reading academic articles and books. During the five weeks of gaming, students learned to become more curious and inquisitive about the game and successfully transferred this attitude to tutorial meetings and class discussions.

Here one could think with Marshall McLuhan about games as epistemological devices, less carriers of information than shapers and enables of human experience and cognition. In my current teaching on an introductory module to Anthropological texts and films at the LSE, I have followed this approach and introduced ‘serious’ games such as Phone Stories, Balance of the Planet or Papers, Please as class activities. Answering the question of how impersonating the role of a border officer, an e-waste scrap worker or of a ‘green’ public financer may contribute to shaping future anthropologists’ understanding of concepts such as ‘exploitation’, ‘the State’ or ‘sustainability’ would likely take an additional ALLEGRA thematic week. Rather, it’d be useful to conclude this section with Gayatri Spivak’s recent admonition (2011) that as educators we have an obligation to consider how our teaching practices implicitly ‘train’ the imagination of our students.

Consciously training the imagination requires that we recognise the inescapable need to inhabit the ethical world of others if we want to attain the most plausible representation of their social world.

I posit to you that such recognition may also be arrived at through a form of ‘radical play’ that makes explicit – and not simply more fun or entertaining – the very impossibility of such pedagogical stance. Playing the life of a Chinese migrant through a digital ethnography may not in fact give us any deeper understanding of said migrant’s ethical subjectivity than what nonfiction narratives can already afford. But the interactive act of completing Peng’s journey with our own sensibilities does, at least to my mind, render much more explicit something crucial about anthropology. Anthropology ultimately entails handling the interpretation other people’s lives. What we do with this power ought to be at the core of teaching in the discipline. The explicit ‘constructedness’ of digital ethnographies could then contribute to make the communication of the many contradictions and impossibilities of ethnographic work a more honest, empathetic and participated endeavour.

If you want to learn a bit more about how the game was played in class, scroll down to 3.

Otherwise, go to 4 now.

- Practicalities

The game has been used as one of the teaching activities on AN447, the core component of the LSE MSc Programme ‘China in Comparative Perspective’. Peng was played during seminars in groups of three to four students on iPad devices during five consecutive weekly seminars. All gaming sessions were facilitated by me. The game would save students’ progress in the game and students kept playing in the same group until they reached one of the game’s seven possible endings. Class was organised so that after 15 minutes of gaming, the groups were mixed together and students discussed in pairs what they thought relevant about the game. The remainder of class time was usually spent on a diverse set of teaching activities that would bring topics and readings from different weeks in relation to the game’s storyline.

During seminars, students were prompted to connect what they saw in the game to the social scientific models described in lectures, similarly to what happens with class readings.

However, the immersive virtual environment of the game would spur students to reflexively embed themselves and their game choices in the very material, requiring explanations.

This exercise enabled students to think more deeply about how social sciences construe their object of study and determine the limits of valid explanations. Students were also asked to report on the reasons why they took one decision and not another. This exercise would further elicit students’ reflection of their own life choices as a comparative foil to Peng’s (the second part of this text has more on the ethical implications of digital ethnographies).

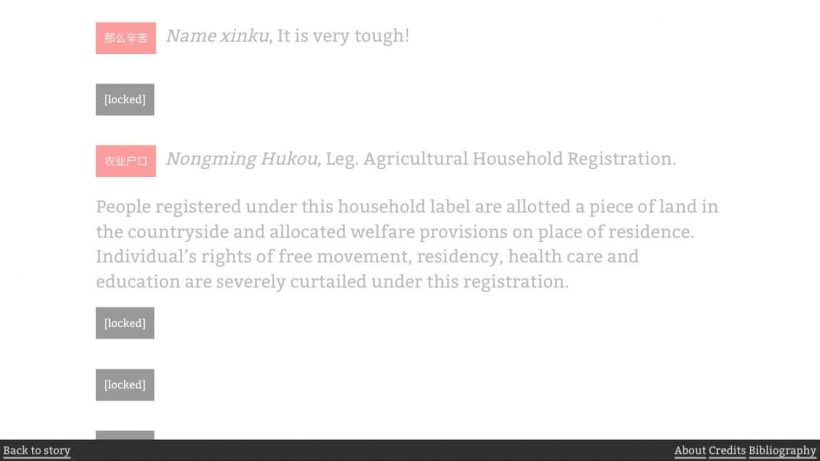

One feature of the Peng game is the interactive glossary. While playing the game, the player encounters specific Chinese expressions that are particularly salient to current debates on contemporary Chinese society. One example is the Chinese linguistic register for discussing migrants and migration projects, which is laden by important political and cultural implications. When students played the game in groups, these terms would spur lively discussions as to their translations and usage. Notably, Chinese-speaking students have been very eager to take on the opportunity to provide their own original interpretations of these terms to their non-Chinese speaking peers and ready to critically engage with the in-game glossary’s definitions of these words.

All in all, the implementation of the game during seminars enabled students to pattern their growing understanding of migration as a social phenomenon in general – and of its Chinese characteristics – with their own sensibility and attentiveness. They also gained insights into what anthropologists call reflexivity: how social life is ubiquitously and uncharacteristically navigated through comparison-like techniques of social likening and othering, and the role that one’s social position or class have on one’s perceptions of things other and alike.

Is there any evidence in support of introducing videogames in class? Well, there is plenty, go to 2.

Are you eager to know what’s coming next? Read 4.

-

- What’s coming next

On Tuesday, Andrea Pia continues to engage with the subtle political and ethical implications of writing ethnographic hypertext. On Wednesday, Ellis Saxey, a collaborator and reviewer of Peng, will go beyond the digitalisation of ethnography to show in practice how hyper-text can be harnessed for the study and preservation of endangered or even dead languages. Something anthropologists have all the reason to consider as one of the most impending goals of their scholarship. On Thursday, Greg Bruno from Project Syndicate relates his gaming experience as one of my students on the very first trial run of Peng as a class activity. Finally, on Friday, Peng’s co-author Marco De Mutiis will look at games that simulate the photographic act of capture as a core game mechanism. He will explore how these mechanisms push forward a specific notion of photography and reinforce the power imbalances of representation and of the relationship between photographer and subject.

***

Andrea says a big thank you to Jakob Krause-Jensen and Ioannis Manos from the EASA’s Teaching Anthropology Network, Agathe Mora and Miiaa Tuomisaari from ALLEGRA and all the participants to the 2017 Teaching Anthropology Conference at Oxford Brookes University, the Digital Ethnography LAB at the 2018 EASA Biennial Conference at Stockholm University and 2018 LSE Education Symposium for the enthusiastically critical support of this project.

Bibliography

Anthropy, Anna 2015. The State of Play: Creators and Critics on Video Game Culture. Seven Stories Press.

Boellstorff, Tom 2006. A Ludicrous Discipline? Ethnography and Game Studies, Games and Culture 1 (1): 29-35.

Cardona-Rivera, R., Young, M. 2013. A Cognitivist Theory of Affordances for Games. In Proceedings of the Digital Games Research Conference: DeFragging Game Studies (DiGRA2013), Atlanta, GA, USA.

Faerber, M. 2015. Interactive Fiction in the Classroom. Available at http://www.edutopia.org/blog/interactive-fiction-in-the-classroom-matthew-farber

Flanagan, Mary 2009. Critical Play: Radical Game Design. MIT Press.

Gee, James Paul 2005. Why Video Games Are Good for Your Soul. Common Ground.

- 2008 “Learning and Games.” The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning. Edited by Katie Salen. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 21–40.

Huizinga, J. 1949 [1938]. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Kardan, K. 2006. Computer role-playing games as a vehicle for teaching history, culture, and language. In Proceedings of the 2006 ACM SIGGRAPH symposium on Videogames Pages 91-93. New York, NY, USA.

Knox, Hannah, Walford Antonia 2016. Is There an Ontology to the Digital? Available at: https://culanth.org/fieldsights/818-is-there-an-ontology-to-the-digital

Laurillard, D. 2002. Rethinking Teaching for the Knowledge Society. In The Internet and the University: 2001 Forum. EDUCAUSE, Boulder, Colorado, pp. 133-156.

Mantz, Jeffrey 2008. Improvisational economies: Coltan production in the eastern Congo, Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 16 (1): 34–50.

Nakamura, Lisa, 2014. Indigenous Circuits: Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture, American Quarterly 66 (4): 919-941.

Pia, Andrea 2016. Dieci anni, nove siccità. La costruzione sociale del rischio in un villaggio rurale cinese, in Ligi, G. (ed.), Percezioni di Rischio: Pratiche Sociali e Disastri Ambientali in Prospettiva Antropologica, pp. 75-106, CLEUP: Padova.

Pun, Ngai et al. 2016. Apple, Foxconn, and Chinese workers’ struggles from a global labor perspective, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 17(2):166-185.

Rutherford, Danilyn 2012. Kinky Empiricism, Cultural Anthropology 27(3): 465–479.

Spencer, Ruelos 2018. A Ludicrous Relationship? A Conversation between Anthropology and Game Studies. Available at http://blog.castac.org/2018/07/ludicrous-relationship/

Spivak, Gayatri 2011. An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Harvard University Press.

Blank, C. 1985. Effectiveness of Role Playing, Case Studies, and Simulation Games in Teaching Agricultural Economics. Western Journal of Agricultural Economics, 10(1): 55-62.

Squire, K. 2005. Educating the fighter. The Horizon 13(2): 75-88.

Squire, K., Jenkins, H. 2003. Harnessing the Power of Games in Education. Available online at http://plato.acadiau.ca/courses/engl/saklofske/download/digital%20gaming%20education.pdf

Sun, Wanning 2014. Subaltern China. Rural migrants, media, and cultural practices. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publications.

Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Featured image by John Salvino on Unsplash.