I met Dr. Giulia Cavallo at one of her art exhibitions in Lisbon, Portugal in 2019. For the Fluid Mosaic project she produced a text that is based on her doctoral thesis and her drawing practice. Cavallo’s contribution teaches us about the spiritual healing practices in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique. She explains the act of healing as a possibility to open individual “paths” that got closed. In the fluid mosaic model, these “paths” can be thought of in association with membranes. In animals’ cells there is a bidirectional communication between the inner and outer spaces of their membrane, similar to the author’s explanation of the link between the spiritual and the terrestrial spheres.

This passage of information that blurs dichotomies: inner-outer and spiritual-terrestrial can be used as a metaphor when envisioning Cavallo’s description of the spirits and the communicative “paths” like the membrane’s channels.

“When Paths Are Closed”

Personal reflections on fieldwork, ethnography and drawing.

Giulia Cavallo Ph.D.

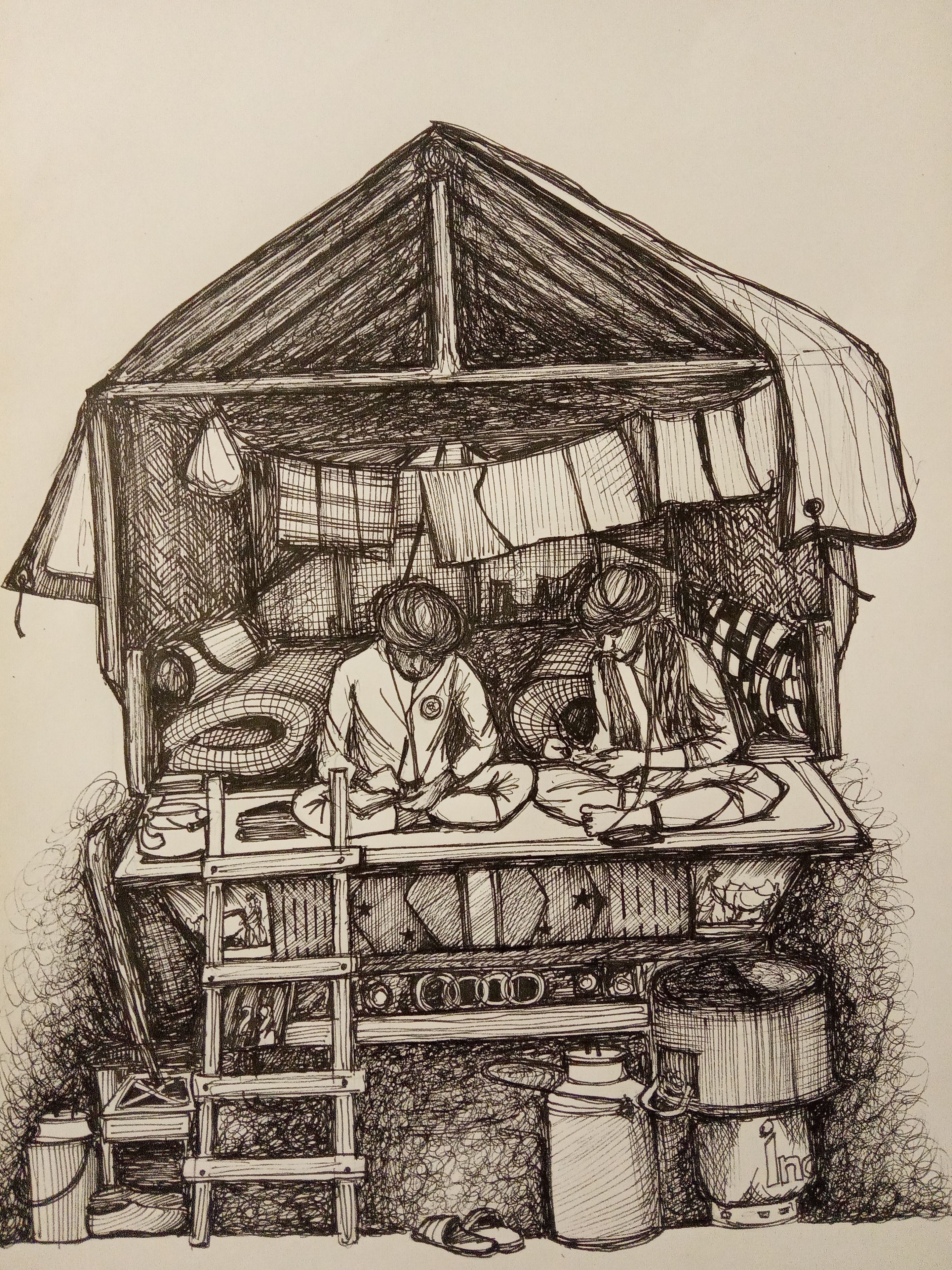

In 2010 I spent almost one year in Maputo doing fieldwork for my Ph.D. dissertation, observing and analysing the therapeutic practices of Zion churches in Mozambique’s capital.

Zion churches are classified as AICs, African Independent Churches, and today they represent a transnational phenomenon that cross different Southern African regions. Their origin goes back to Zion City, in Illinois (USA), where the preacher John Alexander Dowie founded the Christian Apostolic Catholic Church in 1896. Zion churches distanced themselves from the local missionary churches and began to constitute a special category called amazyione in Zulu (or mazione, as named in southern Mozambique), in opposition to Protestant orthodoxy. Nowadays in southern Mozambique, Zion churches are one of the most widespread religious movements.

In Zion churches in Maputo, disease and health continue to be understood according to relational principles that establish who might be related and how, and who, by contrast, has no chance of joining the family. In this view, the spirits of the family (the ancestors) continue to play a key role, and their collaboration ensures the well-being of their offspring. However, there are differences regarding the “traditional”[1], pre-colonial, spiritual universe, since nowadays the ancestors have to submit to the authority of the Christian God and the Bible. The Zion churches reformulate every day the local perception of evil, which it is still connected to the logic of kinship allegiances, through healing practices. In this context, the act of healing consists first of all on the possibility to open individual “paths” (caminhos, in Portuguese) that were closed by the past. This last one, is habited by vengeful “spirits of tradition” and witchcraft that have to be domesticated to Christianity. Only the conversion of these spirits can help ‘open the paths’ (abrir os caminhos) and lead to a future of opportunities.

During that year of fieldwork in Maputo, I was submerged in its urban spiritual complexity, in a religious environment where boundaries are blurred, and trans-religiosity is constant; where Christian, Islamic, and “traditional” practices are permeable and reinvented.

After that very long and intense year of fieldwork, I spent almost two years writing, attempting to describe with words the complex local spiritual world that Zion churches in Maputo reshape every day through their practices. In the backyards of the pastors who received me every day, who fed me and opened their doors to me, I encountered stories of witchcraft, spirits, sorcery, mental illness, bared women, suffering women, single moms, lonely grandmothers, alcoholic men.

In Maputo, spirits are not visible. At least, not for me. I have never seen one. But I saw what they can do. How they can manifest themselves during a ritual, in a living person. I can assure that they are present, they have a story, they have an agency in individual actions, in everyday life. There is a constant communication between the living and the spiritual world. This communication is ambiguous, not always peaceful, linear, congruent. As the healing processes. And I personally felt this fluid heterogeneous coexistence of traits. I embodied it. It was present in people’s narratives and actions.

But how do I truthfully explain it in other ways that is not based on scientific words as the base of my doctorate dissertation? How do I tell about the sense of insecurity that constantly permeate people experiences? And, finally, how to show that these same stories started to be deeply entangled with the way I was experiencing Maputo? How do I show what is invisible to the eyes, but deeply felt in the body?

In 2015, few years after the conclusion of my doctorate, I started a new phase of my life. In that moment I couldn’t advance in my academic career, some personal and professional situations were stuck, and I decided to change my route. I started to draw, every day. Since then, drawing became central for me. It became a new way to see the world, and to organize it. A new state of mind.

Drawing became also a new tool to explore my ethnography and to reflect on it. It allowed me to communicate what was unspeakable, turning visible what was invisible. Even my emotions during fieldwork, not visible in my academic text.

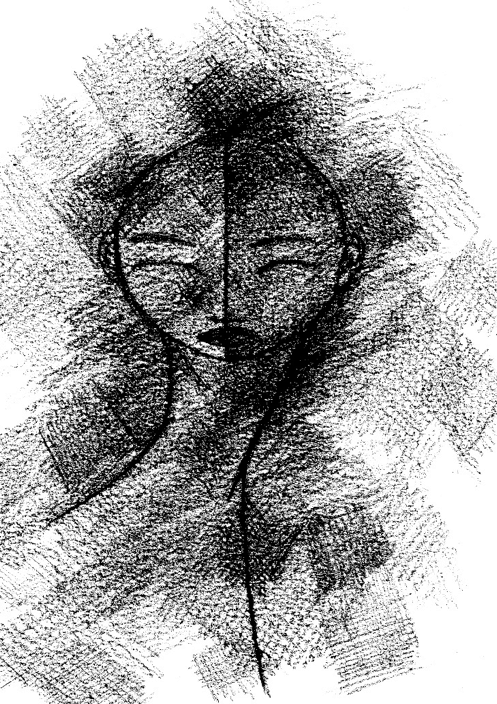

Munyama represents one of the more enigmatic words during my fieldwork. Actually, nobody could explain to me this word in a clear and straight way. For almost one year, I thought munyama was a generic name referring to a bad spirit possessing a living, but it is not. Munyama literally means darkness, in Changane and Zulu languages, and it is a spiritual condition: it is a state of pollution that causes vulnerability to spiritual aggression and that “close the paths”. It is a kind of affliction, very similar to a state of disease. And it is only possible to “have munyama” if, for example, ancestors are withdrawing their protection causing the permeability of the body to spiritual attacks, if some ritual has not been properly executed or has been neglected, or (and this is one of the main cases I found) if the individual has inherited a spiritual condition from his/her ascendant kin and he/she doesn’t know. Munyama turns socially invisible who is affected by it: this darkness is felt like a black veil covering the individual, as once it was described to me by a young woman. The body is completely vulnerable, the “paths close”, and life gets a brake. This enclosure is revealed from the incapacity to find a good job, or by marital bad relationships, or through the fact of having difficulties to get pregnant, etc.

In a certain way, I can say that this social invisibility, paradoxically, is caused by an excess of visibility, and thus, of a sense of vulnerability. People are always worried of being observed too much, measured, envied. A sense of persecution and spiritual insecurity is diffused. I personally felt this in my own body. Every little movement in the city, or tiny change in my body was noted and commented. This drawing represents also me, quickly walking in the city, with a constant sense of scrutiny I’ve never felt before.

Visibility and invisibility.

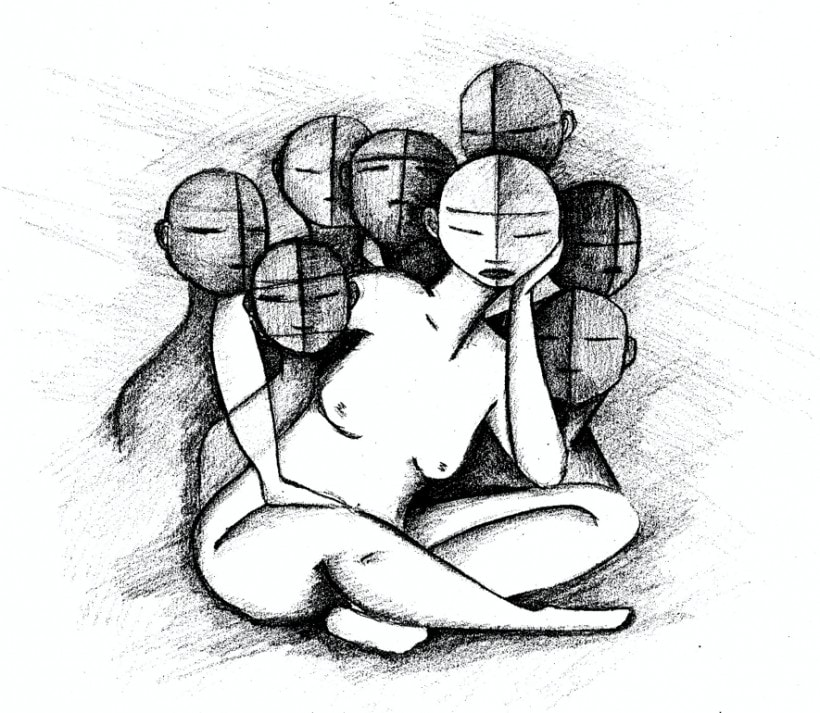

Individuals who feel invisible, often decide to go to a spiritual healer. Christian or not. And the main power of the spiritual healer is to not only again turn his/her patients (through a long and sometimes laborious process) socially visible, but also to turn visible the spiritual realm, through their own bodies and voices. The healer body becomes a vehicle of communication and long-term negotiations between the living and dead.

During the consultation, the patient’s ancestors and healer’s spirits communicate, then, the ancestors decide which kind of therapy is more comfortable for them. Ancestors and patient. The visible part of the individual is just the minimal part of his/her being. Because an individual is multiple. His/her kin-related spirits are ontologically connected to him/her. An ancestor cannot be separated from their own family, especially when s/he has a xará[2], a namesake. And when he/she is not connected to his/her kin-related, the spirit is in a wrong position and can become a problem for the livings.

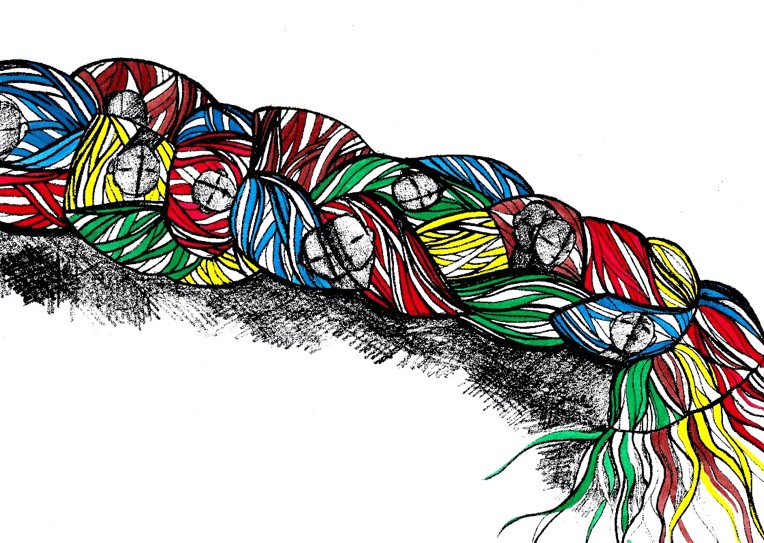

In Zion churches, the use of specific objects during healing rituals, as ropes, gowns or cloths, facilitates the entry of spirits into the human body space. The presence of the ancestors is intensified by clothing through a specific material world. Concerning the strings, called xifungo, pastors rarely knew how to answer about their biblical references and the origins of this type of resource. Xifungo literally means oath (from the verb kufungela, to swear). Originally, the ropes entailed an oath, a request. In the churches I worked with, xifungo seemed to be more closely linked to the symbolic concept of “tying”. In this sense, tying not only corresponds to the physical act of tying the rope to the waist or other parts of the body, but also to the act of tying a spiritual entity, for the purpose of holding it for protection or of leaving the body.

The string tichakachaka, which unite the entire set of colours used by Zion, is always present during masses and rituals. As they explained to me, this kind of string, and other kind of ritual objects, as ropes, cloaks and caps, do not only symbolically represent all the ancestors (matrilineal and patrilineal), but they physically hold them in the material world. They are a kind of powerful catalysts of the spiritual realm, as are songs and some specific rhythms played by the drums.

In this perspective, religious rituals manifest the continuity and fluidity between livings and dead, their need to maintain communication and contact, and in some way, to maintain a memory of the past.

The material world can contain the spirits, as do the living bodies, in a continuum not explicit in everyday life, but fully revealed by religious practices.

On my side, on the surface of the paper, I tried to give visibility to these narratives. This attempt is entangled with a storytelling, but also with a very personal cognitive exercise. Since I was a child, I have a specific way to organize knowledge and information in my brain. I need to visualize it in a touchable and sensorial structure, or I get lost. I find this not so far from the colourful and material world of Zion churches, and how they organize relationships and information.

Drawing allowed me, in synergy with writing, to organize in a graphic way the magmatic, sometime incoherent, flux of information people gave me during fieldwork. These drawings talk about the people I met, but, mostly, about my encounter with them. I draw my process of understanding and caring about this encounter, turning visible what before was invisible to me, and that now is so familiar. A very personal process of learning and communication which reveals my fully presence in the field.

Thesis: Cavallo, G. 2013. Curar o Passado: mulheres, espíritos e “caminhos fechados” nas igrejas Zione em Maputo, Moçambique, ICS – University of Lisbon, PhD dissertation

[1] Tradition is an ambiguous term which became emic in Mozambique, and it is often used referring to spirits and witchcraft. I maintain this word, but in quotes, taking this premise in account.

[2] Xará is an Amerindian (Tupi, Brazil) term which entered the common language of Mozambique, mostly through Brazilian soap opera in the years 1980-1990 (Pina Cabral 2010). In Changane xará is mavizweni, but personally I have never usedthisterm andoftenpeople resortto the wordxará.

Featured image by Giulia Cavallo.