“If we fail to defend our cause, then we should change the defenders, not the cause.”

(Ghassan Kanafani)

Oslo has often been defined as a watershed moment in Palestinian history. It is commonly referred to as the rupture point in Palestinian politics, marking the beginning of the resistance movement’s decline and thus the end of the previous ‘golden era’ of revolutionary successes. The debate on how to overcome the Oslo Accords’ tragic predicaments has often focused on the political transformations it engendered and has paid only little attention to the dynamics, transformations and trajectories that led up to ‘the Oslo capitulation’ or, to use Edward Said’s words, “the Palestinian Versailles”.[1] This paper will briefly examine the history of the struggle, posing an emphasis on the Oslo process in order to articulate the current political conundrum. Furthermore, it offers insightful ways of redressing the crisis of the Palestinian movement, leadership and struggle.

In the aftermath of the Nakba, the Resistance Movement conceived and framed the struggle as justice-centered, infused with anti-colonial spirit, in which the liberation of ancestral Palestine from Zionist colonization and the return of its indigenous population were understood as inherently interconnected goals. Total liberation and return were two faces of the same coin, two concepts impossible to separate. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Palestinian students, along with other sectors of Palestinian society, established popular and guerrilla groups, organisations, parties and unions by advancing the principles of justice, liberation and the return of the refugees for the entire nation.

In the late 1960s, these popular organisations and parties took control of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) institutions, which were still being run by Palestinian notables and elites, and turned the organisation into a more popular expression of the people’s will. The PLO then became the umbrella institution under which the broad-based popular movement operated and “functioned according to the ethos of the time, based upon the model employed by national liberation movements worldwide in the anti-colonial struggle for liberation.”[2] Not only was the Palestinian movement inclusive, a direct expression of the Palestinian “imagined community” and its ambition for liberation, but it was also conceived by its people and perceived by its allies as a revolution based on an “indivisible sense of justice for all” and strongly connected to the struggle of other liberation movements.[3]

Photo by Stefano Corso (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

However, “the PLO suffered a series of profound seismic shocks”[4] that affected its ability to maintain a strong relation with its people and keep voicing popular ambitions in its quest for justice and liberation. These shocks were in large part influenced by regional and global power shifts but nevertheless acted as a catalyst to alter the fate of the Palestinian national liberation struggle. Events in the 1970s, such as Black September in Jordan and the 1973 October War, required the PLO to elaborate new strategies for the struggle: the changed Arab scenario and the different alliances and political interests in the region demanded a renewed attention to the international arena and compelled the effort to achieve international recognition.[5]

These considerations led to the adoption of a transitional political program, known as the Ten Points Program, in 1974. The new platform called for the establishment of a “fighting national authority” on any free Palestinian territory as a first phase towards establishing a secular democratic state in ancestral Palestine. The 1974 program represented a pragmatic choice to enhance the PLO position on the Arab and international arena by achieving international recognition and gaining ”space for manoeuvre” at the diplomatic level.[6] Even though the program avoided any formulation that could endanger Palestinian basic rights, including the “right of return”,[7] it still represented an initial shift in the language and rhetoric of the PLO towards a greater pragmatism.

A more profound crisis with negative impacts on the PLO transnational institutions and its relationship with its constituencies, particularly those living outside the West Bank and Gaza, blew up at the beginning of the 1980s, when the PLO was forced to evacuate Beirut in 1982 following Israel’s attack on Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. As a result, its structures and apparatus lost their cohesiveness and effectiveness and underwent a process of bureaucratization that negatively impacted on the popular organizations and unions, especially those in al-Shatat,[8] causing their role in the struggle to rapidly erode.[9]

In this context, boasted by the renewed momentum that the 1987 Intifada gave to the Palestinian struggle, the PLO attempted to reinforce its connection to the people by rearticulating a clear political strategy. In November 1988, the Palestinian National Council PNC declared the Independence of the Palestinian State, finally opting for the two state solution.[10] While the declaration remains a powerful, touching and passionate text that encompasses the essence of the Palestinian identity and struggle, it details an incontrovertible strategic shift from a “just solution” to an “acceptable solution.”[11] Despite the proclamation, however, the PLO was not able to prevent the deterioration that the 1982 crisis in Lebanon had triggered and that became even more profound with the 1990-‘91 Gulf War.[12]

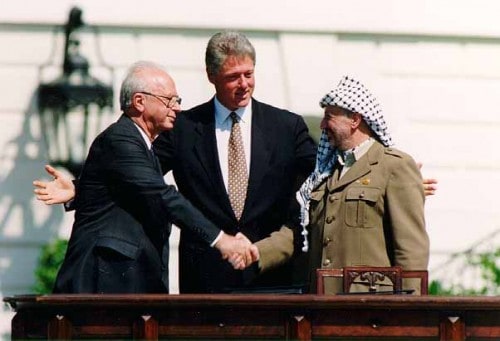

It is in this historical context that Oslo should be analysed, looking at the several transformations and crisis, at what was achieved and what was lost on the long road that led to the 1993 Agreement. The Oslo Accords de facto formalised the shift in PLO political discourse and strategy: the focus was gradually moved from “liberation struggle” to state-building processes and practices concerned with land, boundaries and representation rights.

Depriving the struggle of its foundational principles and undermining its unity of intents, Oslo has overturned the original aims of Palestinian politics:[13] neither liberation nor return and justice were achieved. Rather, the accords brought about political and economic dependence from the occupier, and the atomisation of the society. Finally, they de-legitimised a leadership that ended up acting as the gatekeeper of the interests and security of the occupier.

Photo by Vince Musi (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The Oslo Agreement was an attempt to institutionalise the geographical fragmentation of the Palestinian people into a plethora of diversified political interests, ambitions and struggles.[14]By reducing the Palestinian anti-colonial struggle for justice, liberation and return to a mere negotiation of “land for peace”, peace process transformed the geographical fragmentation imposed upon Palestinian society into a fragmentation of political ambitions, discourses and strategies. The Palestinian struggle for justice has been “chapterised” in turn as “the green line” or a “borders issue”, the “Jerusalem issue”, the “Gaza issue”, the “Israeli-Arab citizens issue”, and the “refugee issue”, just to name a few. While attempts to singularly address all these matters have been made at various political and diplomatic levels, the overarching political discourse was constantly overlooked, as if these “different issues” inhibiting justice were not all part of the same comprehensive struggle.

This political fragmentation was (re)enforced by the establishment of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) and the consequent marginalisation of the PLO. This repositioning of the PLO and its political and infrastructural transformation has fundamentally contributed to the isolation of Palestinian communities, “issues”, and politics.

In fact, with the Oslo Accords, the transnational national liberation project, as originally spearheaded by the PLO, has been ruptured and the political and geographic divisions that individualised the Palestinian struggle have been reinforced. The PLO has become an empty shell, sustaining itself on the legacy of what it used to be, what it symbolically stood for, and what millions of Palestinians have been hoping it would become again: as a matter of fact, it has left the political ambition of its people in a vacuum.[15]

The consequences of this process of “depoliticisation of the Palestinian struggle”[16] are evident in the Palestinian internal dynamics over the past few years and in the dark crisis that the movement is still living.

Since the signing of the Accords and the illusion of peace, the national movement has precipitated into a general paralysis of strategies and grassroots mobilisation. This paralysis was engendered by the annihilation of the very essence of the struggle: the belief “that liberation can only be attained when our strategies are not divorced from morality”[17] was replaced by neutrality and the meaningless language legitimised by Oslo.

This paralysation has nourished the isolation of the Palestinian leadership from its popular constituencies – part and parcel of the liquidation of Palestinian rights and the imposition of “normalised” relations between the coloniser and the colonised, which has made the Palestinian leadership complicit with the occupier within a neo-colonial framework. In this context, the crisis between Hamas and Fatah and the failed reconciliation attempts over the past eight years have been the most evident attestation of the new tragic strategies set up by Oslo and the more complex colonial condition imposed on Palestinians.

Similarly, the Palestinian statehood bid at the UN in 2012 should be understood as part of the political shift ratified by Oslo. The state declaration – coming in one of the darkest moments of Palestinian history, with a stale leadership interested more in re-gaining international legitimacy rather than popular support – was only another attempt to ensure the perpetuation of negotiations, economic and social normalisation, and security cooperation in line with the ‘Oslo spirit’. This strategy confirms the “obsession” of the Palestinian leadership with state-building practices and uncritical compromise, the obstinacy to deny the tragic consequences that the forsaking of the anti-colonial framework has meant for the Palestinian struggle and the Palestinian people, especially the refugees. Moreover, it underlines the inability to reposition justice and liberation at the centre of the struggle and at the same time, the incapacity to resituating the Palestinian revolution into the wider context of transnational resistance against oppression and colonialism.

In line with this pragmatic approach, the Palestinian establishment and the historical parties have been incapable – and unwilling – to re-think their role and that of the Palestinian struggle in the Arab popular revolts. Several analysts have pointed out how Arab revolutions could have favoured the revitalisation of the Palestinian liberation project, a re-articulation of an anti-colonial vision based on regional solidarity.[18] The Arab Spring inspired Palestinian youth “unencumbered by the legacy of PLO factionalism”[19] that took to the streets in the West Bank demanding unity and a change in the strategies of negotiation and compromise. Yet, while these unorganised groups attempted to revitalise the political dialectic within the Palestinian movement, the historical factions and several sectors of Palestinian society, engulfed into the neoliberal social and economic project induced by Oslo, were unable to mobilise for a radical change.[20]

Photo by Wall In Palestine (flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

This incapacity has been particularly problematic in the context of the Syrian revolution, with the Palestinian camps under siege: almost the entire spectrum of the Palestinian political actors (with the only exception of those factions outspokenly supporting the regime) have distanced themselves from the popular revolts in Syria.[21] As Qutami has argued, while Palestinian refugees have been struggling to survive another Nakba, “many of the established Palestinian parties have run in opposite directions, abandoning their responsibilities to the Palestinian refugees of Syria. Palestinian refugee abandonment is symbiotic and complacent with the Zionist project of erasure of Palestine and of the Palestinians and territorialisation through colonialism of the region at large.”

In light of the developments in Palestinian politics induced by Oslo, I argue that the only way to redress the injustice precipitated by the Accords is to address the shift in the political vision and discourse of the Palestinian movement and reframe the whole struggle to its original anti-colonial nature.

It is necessary to relocate the Palestinian cause into the broader framework of a struggle for justice and liberation, the only framework and struggle that can be successful in confronting the colonial condition of both society and land.

Palestinians should recover the unity of intentions and foundational principles guiding a transnational grassroots movement as the basis for their struggle. The Palestinian people should reunify themselves, not in rhetorical means, but along the lines of a political project in order to overcome the dispersion and ‘rebuild’ their society around a shared understanding of the intrinsic and inextricable cohesion of the struggle for total liberation from the colonial superstructures imposed on their lives. This process would surely require serious analysis and honest debates over how to re-organise the people and the struggle, how to mobilise the new generation and how to encompass the multiplicity of experiences, visions, background and ideologies that characterise Palestinian politics, but it is a necessary step for revitalising the national movement.

It is also necessary to re-contextualise the Palestinian question into the long history of anti-colonial revolutions: the Palestinian struggle should be analysed and understood through a different lens, a dimension that does not conceive Palestine as an isolated struggle. Rather, it is important “to restore the sense of the indivisibility of justice”[22] that was at the basis of the Palestinian revolution and consider “the particularities of Zionism as part of the genealogy of settler-colonialism and injustice transnationally.”[23] It is fundamental to find again the spirit of commitment toward other oppressed people and the sense of responsibility towards all the other struggles for liberation, freedom and justice that used to animate the Palestinian movement.

Featured image by Wall In Palestine, flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Footnotes

[1] Edward Said “The Morning After” London Rewiew of Books Vol. 15 No. 20 · 21 (October 1993) accessed 5 June 2014 http://www.lrb.co.uk/v15/n20/edward-said/the-morning-after [2]Karma Nabulsi, “The PLO: A Positive Model or Doomed for Failure? Part II Roundtable on Palestinian Diaspora and Representation” inJadaliyya accessed 10 January 2013 http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/1681/the-plo_a-positive-model-or-doomed-for-failure-par. [3] Rabab Abdelhadi “Debating Palestine: Representation, Resistance, and Liberation” in al-Shabaka (5 April 2012) accessed 6 May 2014 http://al-shabaka.org/debating-palestine-representation-resistance-and-liberation?page=2 [4] Karma Nabulsi, “Participatory Models of Democracy and the Refugee Issue.” Working Paper prepared for the IDRC Stocktaking Conference on Palestinian Refugees, (Ottawa, June 2003), accessed 10 January 2013 http://prrn.mcgill.ca/research/research_papers.htm#articles 7. [5] Macintyre Ronald “The Palestine Liberation Organization: Tactics, Strategies and Options towards the Geneva Peace Conference” Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Summer, 1975), pp. 65-89, p 76 [6] Jamil Hilal “The Challenge Ahead” Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Autumn, 1993), pp. 46-60, p 49 [7] Ibid. [8] The closest translation of al-shatat is “Diaspora”. However, the use of the term Diaspora with reference to the Palestinian case is inadequate. The definition of Diaspora does not address their legal status, and further, “accepts a situation of dispersion […] which implies the abstraction of the right of return. To qualify the Palestinians as Diaspora, is to eliminate the language necessary to change their situation”, Kudmani, quoted in TareqArrar, “Palestinians exiled in Europe” in Al Majdal (Spring 2006) pp. 41-45 p. 42. [9] Hilal “The Challenge Ahead” 48 [10] Ibid 48 [11] Shafiq al HoutMy Life in the PLO, ed Jean Said Makdisi and Martin Asser trans Hader Al Hout and Laila Othman (London: Pluto Press, 2011) p252 [12] Jamil Hilal “The Challenge Ahead” p 49 [13] Ibid [14] Alain Gresh “The Palestinian Dream On”, Le Monde Diplomatique, 149, (Paris, Jul/Sept 1998).[15] The author had articulated on the Palestinian political and social fragmentation induced by Oslo in a previous article appeared on the PYM bookletPYM commemorate 65 Years of Nakba (15 May 2013)

[16] Massad “Oslo and the end of the Palestinian Independence” [17] Omar Shabban “Palestinianism as the antithesis to Neutralism” Beyond Compromise (14 April 2014) Accessed 14 April 2014 http://beyondcompromise.com/2014/04/14/palestinianism-as-the-antithesis-to-neutralism/ [18] MajedKhayali “Palestinian in the context of the Arab Spring” Middle East Monitor (28 January 2013) accessed 5 June 2014 https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/articles/middle-east/5099-palestine-in-the-context-of-the-arab-spring see also Zarefa Ali and Amal Zayed “The Arab Spring and Reviving the Hope of Return”Badilaccessed 5 june 2014 http://www.badil.org/en/al-majdal/item/1928-art6 [19] Raja Khalidi “After the Arab Spring in Palestine: Contesting the Neoliberal Narrative of Palestinian National Liberation” Jadalyyia (23 March 2013) accessed 5 June 2014 http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/4789/after-the-arab-spring-in-palestine_contesting-the- [20] Ibid. See also Ben White “Why has there been no ‘Palestinian spring’? One word: Oslo” The Gardian (11 June 2012) accessed 7 June 2014 http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/jun/11/palestinian-spring-oslo-accords [21] Majedkhayali “Palestinians in the midst of the Syrian revolution” Middle East Monitor (29 July 2012) accessed 7 June 2014 https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/articles/middle-east/4060-palestinians-in-the-midst-of-the-syrian-revolution [22] Abdelhadi “Debating Palestine” [23] LoubnaQutami “Rethinking the Single Story: BDS, Transnational Cross Movement Building and the Palestine Analytic” Social Text (17 June 2014) accessed 17 June 2014 http://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/rethinking-the-single-story-bds-transnational-cross-movement-building-and-the-palestine-analytic/

Thanks for the hard work, following our translation by diffusion in Italy.

Rosario Citriniti – Turin – Invictapalestina.org

https://invictapalestina.wordpress.com/2015/10/31/gli-accordi-di-oslo-e-il-rovescio-della-medaglia-palestina/