Rachel E. Black. Porta Palazzo: The Anthropology of an Italian Market. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. 232 pp. ISBN 978-0-8122-4406-9

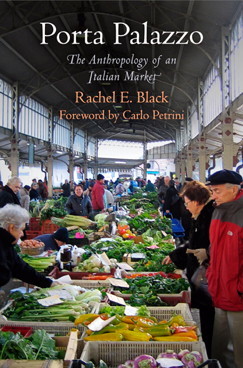

The book under review, published in 2012, is an anthropological study of Porta Palazzo market in Turin. The Canadian anthropologist, Rachel Black, drawing upon fascinating extensive fieldwork, stresses the role of the market as a social space beyond its economic meaning. What Black is most interested in is the social aspect of food provisioning, a practice which, in her opinion, has been overlooked in favour of a stronger focus on production, distribution, preparation, and consumption of food. In contrast with supermarkets, which depersonalise and standardise shopping experiences, the market is animportant “place of sociability in cities where public spaces are increasingly deserted and inhospitable” (p.4).

Black explores the dynamics that keep institutions such as Porta Palazzo running despite their apparent economic inefficiency. Referring to Polanyi’s and Geertz’s understandings of economic exchanges as socially and culturally embedded, she identifies a combination of social and economic transactions, in which “economic exchange facilitates social interaction and create a space of sociability” (p. 7).

Black’s analysis is based on long-term fieldwork at Porta Palazzo market, using participant observation – together with a small number of interviews – as the main research method. Experiencing the market from the shopper’s perspective at the beginning of her fieldwork, the author subsequently managed to penetrate the vendors’ field by working or helping in different stalls. Through a holistic approach, the book presents a series of narrative snapshots of people working and shopping at Porta Palazzo, framing the market as a place where “friendships are made, families are reunited, ethnic and cultural tensions are negotiated, and local identities are constructed” (p. 2). In this way, different types of sociability at the market and conditions for accessing this social world are explored.

In the first chapter, Black presents the market as a field of study. The author’s personal experiences in accessing the field and interacting with its social actors are discussed along with techniques for ethnographic research.

Chapter two, drawing upon secondary sources and archival research, provides an historical overview of the city of Turin and changes in Porta Palazzo market as the urban space developed.

Chapter two, drawing upon secondary sources and archival research, provides an historical overview of the city of Turin and changes in Porta Palazzo market as the urban space developed.

In the third chapter, the author sets a bigger picture of the market as it appears today, in order to contextualise subsequently presented snapshots. Developments that occurred in the market’s makeup at the time of fieldwork – particularly a big renovation in 2004-2006 – are discussed.

The four following chapters provide the central themes of the investigation. In chapter four, consumption is analysed as a form of moral evaluation. The market is presented as a place where interactions can generate anxiety, especially with regards to normalised gender and social norms. The carnivalesque nature of the marketplace allows for a transgression of such norms, at the same time reproducing concerns related to socially accepted identities and roles.

The fifth chapter investigates the market as a point of references for migrants, who, in the last few decades, have arrived to Italy on an increasingly conspicuous basis. Large-scale immigration is associated with tensions within Italian society. The market is often the first place where “the Other” is approached and discovered. However, such encounters are not always happy multicultural events: interactions between Italians and migrants in the marketplace often reproduce large-scale social conflicts and racial prejudices.

Chapter six approaches local administration’s attempts to efface the image of the market as a degraded and potentially dangerous place by presenting Porta Palazzo as a multicultural centre where both local and foreign traditions can be experienced through the exchange and consumption of food. Ethnographic culinary tourism at the market is meant to build up bridges between different cultures by framing diversity as something that can be – both literally and symbolically – tasted and appreciated. However, this approach, which is supported by media and marketing operations, has also its downsides.

Finally, chapter seven focuses on Porta Palazzo farmers’ market as a point of contact between city and countryside dwellers and one of the last connections between consumers and producers. An analysis of the notion of “eating local” and related knowledge concerning food, language, and practices, is brought about. The four main chapters end with a recipe that the author learnt in her interactions with market’s shoppers and workers.

Black’s book stimulates a discussion on models of provision and consumption that are alternatives to those envisaged by multinational companies and globalised brands. The author makes a great point by underlining that such models are to be understood not only in a purely economic, but also in a social – and, I would add, political – dimension. As Black rightly argues, economic exchanges do not necessarily deny or contradict the social: on the contrary, they might favour proximity and interaction between people. In this sense, shopping at the market can be associated to other practices entailing both material and non-material transactions and fostering mutual relationships between individuals and groups, such as gift giving and hospitality. As Black maintains in regards to the market, such practices and institutions are still meaningful in people’s everyday lives, even though they are demanding in terms of time and energy and generally not driven by a “maximising profit” rational.

The representation of Porta Palazzo as a sort of Maussian “total social fact”, where different institutions – from social, to political, to economic – converge and interact, and various social actors (consumers and vendors, locals and foreigners, men and women) come in contact with each other, is insightful for understanding multifaceted dynamics underpinning the market’s life. The author’s extensive fieldwork, which brought her in close contact with the market’s “population” and their professional and personal life stories, is an important example of the complex – and often insidious, yet exciting – interaction between everyday life, human relationships, and research work which ethnographers experience. Black’s long-term personal involvement and intimacy with the market environment results in a fascinating picture of Porta Palazzo, also as a – sometimes repellent – sensorial experience made up of smells, sounds, colours, and, of course, tastes (ch. 3).

In my opinion, however, Black’s focus on “social aspects” of the market has two main – and related – flaws. First, while pointing out many anthropologists’ – and journalists’ – attitude of representing markets “either as picturesque elements of everyday life or as tourist attractions” (p. 6), the author partly shares this approach, sometimes providing a too uncritical and almost “exoticised” picture of certain features of the market. The introductory claim that, in North America and Western Europe, markets like Porta Palazzo fulfill the desire “to connect with our food, to know where it comes from and how it is grown, and to learn about different culinary cultures” (p. 3) addresses social and economic dynamics underpinning such institutions on a very partial basis. And the – in my view crucial and indisputable – criticism raised in chapter 6 with regard to ethnographic tourism and the “celebration of diversities” through a commodification of different traditions is just outlined and not problemtised further.

Throughout the book, concerns about local food, culinary traditions, and the encounter of different cultures – strong suits of the Slow Food movement, whose founder, Carlo Petrini, authored the foreword to Black’s work – seem to have priority over other, more “economic” issues, in the analysis of the market’s dynamics.

Although the author is right in attempting to look beyond the strict economic significance and functioning of Porta Palazzo, sometimes this obscures crucial features of the market institution. An analysis of the deep social conflicts and political and economic crisis specific to the Italian context is indeed provided (chs. 2, 5, and 6). However, fundamental points raised in this discussion, for example, the phenomenon of old people searching through the market waste (ch. 4), seem to be approached just superficially, in favour of a deeper attention to exchanges of national culinary traditions, or convivial interactions around the market stalls.

This is not to say that Black’s ethnography of Porta Palazzo provides the image of an artificially “exoticised” space where (presumably) locally produced and organic food is sold at high prices to satisfy local middle classes’ desire for “craft” and “traditional” products – as it is the case for some farmers markets in the UK, for example. Porta Palazzo is nothing like that and Black proves to be well aware of the multiplicity of interactions and conflicts, predicated upon gender, race, age, and social status, which underpin the market’s life. However, issues concerning social and economic insecurity, the reconfiguration of the public space, as well as limited and exclusive access to such spaces, would deserve a deeper analysis, especially in a context such as present day Italy, which is experiencing increasing social, political, and economic inequality and marginalisation.

In summary, with the hope that the criticisms offered in this review can serve as a constructive basis for further research, the book is, without doubt, an inspiring contribution to economic anthropological studies. Supported by a strong methodology, Black’s ethnography provides important insights on how economic institutions are embedded in, and underpinned by, social relationships vis à vis depersonalised and alienated contemporary models of production, distribution and consumption.

The photographs in this article are from Constanza Curro’s personal photos.