Introduction: Destabilising Concepts

Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård

Moving from the first section of the thread where hundreds performed as much as a method for ordering the messiness of embodied research, as a vehicle for such and the general messiness of ordinary life, in this second section we ask how we may use our bodies and writing to destabilise concepts? Because however much care and attention we pay to every single word and to all Hundreds and thousands of them, we cannot escape the limitations set by words. We cannot as Ursula K. Le Guin (1985) proposes simply “unname” colours, things and beings of our worlds; concepts form our thinking whether we want it or not (Brandel & Motta 2021). They are, as such, both resources for and actors in thinking; trafficking each a host of limitations and allowances. But can we not destabilise concepts to experience, say, a colour “as more a presence than a sign, more a force than a code” (Taussig 2009: 7)? Can we not, at the limit of our sensorial abilities, find a zone for making contact with other worlds, a zone for thinking other thoughts?

However much care and attention we pay, we cannot escape the limitations set by words.

This is exactly what Clara Fuglsbjerg Ebberup asks in her essay that opens the section, and in which we meet her standing in her window sill to imagine what it might feel like to be a plant. The following three essays all revolve around related methodologies that set concepts in motion. But it is not only that concepts are made to move, as the reviewer Donata Schöeller experienced, catching herself on the window sill with Ebberup; these are methodologies that set bodies in motion, literally and imaginatively. In the second text, Katrine Frank Jørgensen takes us on micro-phenomenologically inspired exploration of the concept of response-ability (Haraway 2016) – an exploration that leads Jørgensen to embrace the uncertain and indefinite in academic work. Fine Brendtner in her essay moves the concept “understanding” along the maelstrom of blood that gushes inside us all; Brendtner leads us through arterial and venous qualities and towards fresh thinking about direction, relation and hesitation. Fresh and novel thinking is exactly what Sigríður Þorgeirsdóttir hopes to foster, by bringing thinking and thinkers back in touch with life and living. By employing methods for critical embodied thinking, she shows how we can bring bodily and affective experience into a concept, otherwise most commonly polished clean of such destabilising dimensions.

The experience of reading these four texts together, inspired Schöeller to ponder whether language that may move readers and their bodies “is the mark of a more embodied approach within research”. To us, the texts in this section further show that while some concepts stiffen into ontological dumpings (Hastrup 1999), others seem even in themselves to hold a destabilising force. These are concepts that carry calls for action; approaches to thinking that in and of themselves asks us to act: To “defrost” (Mattingly 2020), “sensitise” (Latour 2014), “quicken” (Guyer 2013) or “enliven” (Ballestro and Winterreick 2022) concepts; to experience the “felt sense” (Gendlin 1981; Schoeller and Thorgeirsdottir. 2019) of phenomena, to develop our “response-abilities” and to “stay with the trouble” (Haraway 2016).

In a reflection of and paying respect to the collective nature of thinking, we have chosen to cite central aspects of the reviewers comments in each section. We hope that this openness shall inspire conversations to continue beyond the thread – beyond this present thinking.

Cite this article as: Smith, Aja and Anne Line Dalsgård. June 2023. “Introduction: Destabilising Concepts”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Limitation as Contact

Clara Fuglsbjerg Ebberup

There is a pelargonium houseplant on my windowsill. I move it to stand there myself. The leaves touch my arm and leave a lemony scent on my skin. Outside a woman walks by – is it silly that I stand here, on a windowsill? Extending towards the sunlight, I hit my forehead against the window and my elbow against the wall. I feel my biology holding me back. It is not comfortable to stand on a windowsill. The white painted wood beneath my feet is cold. It provides no fertile ground for sprouting roots, no foundation for growing, for sensing. Limitation.

The hundred words above, inspired by Lauren Berlant and Kathleen Stewart’s concept of Hundreds (Berlant & Stewart 2019), is a literary attempt to unfold and understand, an experiment to sense the perspective of a pelargonium houseplant. Both this literary reflection and my sensorial attempts to move closer to the perspective of a plant, however, seemed at first to fail. All I sensed were limitations, frustrations, and constraints. But instead of stopping at the frustrating sense of limitation or trying to transcend these constraints, I want, in this essay, to reflect on what speculative and epistemic potential lies in “staying with the trouble” of limitations (Haraway 2016). What happens if I move along (and not away from or beyond) my methodological, epistemological, and bodily limitations? What might I learn from the challenging encounter with a pelargonium houseplant?

Pelargonium houseplants are one of the large wild South African pelargoniums brought to Europe in the 18th century where, through breeding and cultivation, they eventually came to stand in homes in small pots spreading the scents of rose, mint, or lemon. My pelargonium spreads a scent of lemon every morning when I open the window behind it, yet it has never occurred to me to notice it as anything other than an object. Inspired by Natasha Myers’ exercise to cultivate imaginative sensoria (Myers 2014), however, I tried to sense like my pelargonium, to stand on the windowsill as it does and extend towards the sunlight. But I hit my forehead against the window and my elbow against the wall. It was not comfortable to stand on a windowsill like a plant in a pot. I felt limited, and the experiment felt more silly than illuminating, more frustrating than successful. Yet reading Kathryn Yusoff (2013) alerted me to other possible dimensions of the experience: what if the limitation I experienced could tell me something about being a pelargonium? Could it be that the limitations I sensed resembled the limitations of a plant in a small pot on a cold, north-facing windowsill? The perspective of a pelargonium. On the other hand, can I really sense the world like a houseplant?

Such questioning of our ability to sense, understand, and respond to nonhuman worlds is central for Yusoff. In her work, ‘sense’ is both bodily sensory experience (to sense) and comprehension (to make sense), and our ability to sense others is closely related to our capacity for understanding and compassion . Yusoff’s interest centres on how we might come to sense and make sense of that which lies just on the edge of the sensible: the ‘insensible’ . Maybe I experience the sensation of limitation because the pelargonium is ‘insensible’ to my (human) perception and understanding. The limitations and frustrations I sensed might therefore seem like signs of a failed experiment, yet there is theoretical potential in the ‘insensible’ and thus in the sensation of limitation. Yusoff asks rhetorically, “could we ever really grasp just how strange other lives are?”, not to discourage us from attempting to understand beings beyond ourselves but rather to inspire us to address “the surplus that falls short of sense”: that which lies just on the border of our comprehension (ibid, 218, 224).

I do not know whether it is my own limitations, an experience resembling that of the plant, or both that shine through in my sensorial and literary experiments to move closer to the perspective of a pelargonium. But does it really matter?

The experience of limitation occurs in the encounter with something. It is an experience I can have because I have a body – a moved and moving body. Without a body I would not sense limitations: hit my forehead against the window or my elbow against the wall. But nor would I be able to come into contact with other bodies. Without body and affect the anthropologist would not be able to sense and in turn understand, care for, or respond to others. I would neither experience limitation nor comprehension in the encounter with a pelargonium houseplant. Limitation, in this sense, might not be the limitation of but rather a vantage point for ethnographic insight.

The experience of limitation occurs in the encounter with something.

If I think of limitation as a form of contact zone between bodies and perspectives it becomes clear that limitation does not mean delimitation; it is not a sharp line between self and other, between me and the pelargonium. On the contrary, like Mary Louise Pratt’s concept of contact zones, contact zones of limitations are spaces where we “meet, clash, and grapple with each other” (Pratt 2007: 7). They are spaces where bodies and perceptions are unsettled, shaped, and affected by other bodies and perceptions as they tumble into one another in ways that may feel frustrating and silly but simultaneously hold the potential to inspire and excite. These contact zones of limitation hold an epistemological potential, an invitation to address “the edge of the sensible” (Smith 2022), to move along our epistemological and bodily limitations, not to know anything for certain but to allow for some speculative understanding to transpire between our different bodies and perspectives. These, I think, are the troubles and potentials of limitations.

Cite this article as: Ebberup, Clara Fuglsbjerg. June 2023. “Limitation as Contact”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Engaging Concepts by way of the Body

Katrine Frank Jørgensen

How does a theoretical concept feel? And how does my bodily response to a theoretical concept enliven it and make it available? What does it mean to engage with a theoretical concept in a bodily manner and how can such an engagement inspire new forms of bodily availabilities? The answers to these questions are neither simple nor unambiguous but these were the questions evoked in me when faced with the task of micro-phenomenologically exploring Donna Haraway’s concept of response-ability and when later writing Hundreds to flesh out my own sense of the concept.

My body is alive. I live with my body. I live in my body. I live as my body. I am my body. I meet the world and others with my body and together we dance. We intertwine and allow ourselves to be influenced, shaped, changed. We are not delimited physical objects, but malleable in the encounter with others, with something else. A cold tile floor, a word. Sometimes I forget, but I will remember that just that feeling is also a part of my lived and living body. A part of the body with which I am and do.

Exploring a theoretical concept micro-phenomenologically entails directing one’s attention away from thinking about content and towards how the concept is bodily experienced. Micro-phenomenology has proven that one’s understanding of a concept begins in the body and, therefore, we should focus on this bodily response in order to flesh out a concept rather than favoring an essentialized, reified meaning outside of ourselves (Petitmengin, 2016: 30, 35). Approaching the concept of response-ability through micro-phenomenological explorations thus became a way for me to bodily experience this shift in attention by allowing my bodily encounter with the concept to awaken.

When exploring the concept, I remember how I found it hard to feel something at first. I tried to close my eyes and to let the thoughts that appeared in my head float by like clouds, to not let them steer my focus away from my bodily experiencing of the concept. It was difficult, I thought to myself, as I noticed how my body felt awake, but also hesitant. I remember sensing my surroundings clearly, the chair I was sitting on, the distance to the walls around me, and the tile floor my feet were touching. I tried to feel the concept instead of just thinking about it, and after a while, I began seeing an image of unicellular organisms moving in, between, and around each other in flowing movements, both pushing and pulling; unicellular organisms intra-acting with each other (Barad, 2007: 33). Through this image, I then started to pay even greater attention to how the different elements around me felt and how I might affect them as well. Maybe the tile floor under my feet felt the pressure of my shoes against it? The image made me feel as if I was, just like the unicellular organisms, intra-acting with my surroundings.

I continued to feel both awake and hesitant but, in a way, these co-existing feelings and how they affected my intra-action with my surroundings, began telling me something about the concept and what Haraway may have been suggesting when discussing our responsibilities as multispecies organisms living together.

I take response-ability from Haraway, as it refers to the abilities required to live in and respond to disturbing times in an ethically sound manner. In her view we not only have to sensitise our bodies in order to better grasp our worlds, we must also learn to respond ethically to the situations in which we find ourselves; we need to sharpen our response-abilities and engage ourselves with what seems troubling, letting it unfold and affect us (Haraway, 2016: 1). From this perspective, the world is not outside of ourselves, but is rather created with us and through us.

In my bodily experience of exploring the concept, allowing myself to let go of this essentialized, reified meaning outside of myself required me also to accept or at least move with the uncertainty that came with it. As mentioned, the image of unicellular organisms that appeared before my eyes when trying to feel the concept instead of just thinking about it made me pay even greater attention to my surroundings than I already was. It made me think of my surroundings as elements I was intra-acting with, thus allowing a sense of mutual influence to arise. And meeting my surroundings anew in this way, I started to realise, might be what Haraway is suggesting as the first step in approaching a better and kinder way of living together as multispecies organisms. Through paying attention to detail, multiplicity can arise, and the world thereby becomes unfixed, and, most importantly, open to change.

Leaning into co-existing or even contradictory feelings is exactly what is necessary in order to find a point of balance to speak and act from.

In my explorations, I felt this need for an attention to detail when attempting to let go of already established ideas and accept the uncertainty that manifested itself, when I started to think of my body as more than just my body. As I was feeling both hesitancy and wakefulness, I had to navigate with detail, which shaped my intra-action with my surroundings and thus how the concept unfolded for me. I remember how I felt a bit annoyed at myself in the situation for not being able to let go of the hesitancy. However, reflecting on it now, those co-existing feelings were highly important in telling me something about the concept of response-ability. I think what Haraway is suggesting, is that it is exactly through these bodily responses to my intra-action with my surroundings that I am able to tune in on how I respond in the best way possible. Leaning into co-existing or even contradictory feelings is exactly what is necessary in order to find a point of balance to speak and act from.

Cite this article as: Jørgensen, Katrine Frank. June 2023. “Engaging a Concept by way of the Body”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Moving with Blood – An Experiential Anatomy for Thought

Fine Brendtner

This is an invitation. An invitation to feel your fluid body awash in blood as it moves through space. A single blood cell travels from our hearts to our organs, fingers, toes and back again in under sixty seconds; a maelstrom of vital matter gushing inside us. How does it feel to relate to a body of blood? How can we use our bodies to understand fieldwork moments that physically affect us? What is revealed when we move while we ponder the things which move us? These are the questions that my colleague Mette and I explored in a movement workshop we created for the research group Embodying Academia.

~~~

It started with nit-picking and blood. Mette and I sat on the floor of her office and hashed out ideas for an upcoming workshop. The research network Embodying Academia had asked us to join a co-created workshop series on the concept of “understanding” in a context where bodies become the core tool for academic knowledge making. I was the one doing the nit-picking. Carefully, I hesitated over the word: understanding. There was something irritating about the “standing” part. It rang rigid; deceivingly solid. During the past year I had done ship-based fieldwork at sea, where my body of study had been in constant motion, both figuratively and literally. From a marine point of view, ground is replaced by water, steadfastness by motion and understanding is on the move. To make sense of how the materiality of human bodies doing research at sea matters to natural and social sciences, I playfully drew on my personal dance practice as an epistemological entry point. Approaching embodied states as a form of situated, material and practical knowledge making after Haraway (1988), theory became paired with insights from somatic movement practices, such as the experiential anatomy of Body-Mind Centering (Bainbridge-Cohen 1993). In BMC one learns to fine tune one’s somatic perception by visualizing the internal fluids of the body throughout movement exercises. Fluids here mediate the dynamics of flow between rest and mobility and make the dancer present to constant transformation in the flux of alignment. I used this practice to explore the material dimension of embodied research and how it affects analysis at sea, a place where the researcher sways in sync with a seesaw horizon. It let me to ask my share of workshop prompts: What is revealed when we move while we ponder the things which move us? How can we use our bodies to understand fieldwork moments that physically affect us?

Mette recalled a time when she had hesitated at one such moment during her work as a medical anthropologist. It was during her research on healing environments in haematological cancer treatments and care, that she suddenly found herself entrusted with a bag of blood platelets next to a patient’s bed (Høybye 2013). Standing inside the haematology ward at a Danish university hospital, Mette was told to keep the bag moving until a nurse would be ready to set up an infusion. Blood and practices of blood (sampling, counting, measuring etc.) were central to the everyday on the ward and her fieldnotes and interview transcripts were full of it. Yet, when she felt the life-giving substance, mediated by the plastic pouch moving inside her hands, Mette wondered how to put words to the immediacy, presence and meaning in this embodied experience. How does it feel to relate to a body of blood? This was the fieldwork question that she brought with her. We decided to join our explorations.

~~~

When doing fieldwork, most research eventually comes up against the insistent curiosities of material influences from our environment. Admittedly, blood is not usually one of them. In a dance studio, Mette, I, and other research members workshopped our questions through bodily practice. Participants moved in their own tempo, form, and ability. They investigated our questions, while I shared BMC® prompts to guide them in imagining their felt anatomy:

Let your heart lean into your hand and feel it beating inside your palm.

Breathe into that space behind your sternum.

Imagine breathing into your heart, an organ awash in blood, an organ both tender and strong.

Imagine your heart’s rhythm to continue flowing throughout your blood vessels,

into your centre and out into arms, fingers, legs, and toes.

Arterial blood moving from centre to periphery, venous blood moving from periphery to centre.

Move and feel touch pushing from your body into your surroundings.

Move and feel your surroundings push touch into your body.

Using our bodily senses is one of the most primal and everyday ways to engage with and respond to our surroundings. When we build theory by practicing ethnography, it is as much the outcome of informed scholarship as it is a wording of our physical interrelations. As embodied researchers we are the material that brushes against the world and our bodies form our tools for exploration. Yet, how do we come to access what our bodies know?

When we use BMC as a tool for bodily understanding we re-calibrate our ‘somatic modes of attention’ (Csordas 1993.). Improvisation, playfulness, and guided awareness allow for spontaneity in thought and observation that go beyond pre-patterned understandings. With this agentive use of somatic attention, we access a movement-based heuristic of body-mind relations and environmental entanglements. Does such a practice not qualify to access the materiality of fieldwork moments that physically move us; to help us think matter with matter, after material feminist thought; to engage an intuitive dimension of bodily knowing in unexpected sites of study?

To practice somatic awareness in movement exercises, such as those coming out of BMC, allows principles and thoughts to emerge out of that practice. We generate these principles and thoughts through our bodily experience of imagination, guided awareness, and intuitive improvisation. When we move as “a fluid body awash in blood”, imagination and improvisation allow us a novel way to relate and expand our potential for understanding. We experience our positionality in material ways that open nuanced analyses of for instance directionality. In the workshop, we explored an “arterial quality” that pushes touch and thought from our body as the centre to the periphery of our environment. Alternatively, we changed our mode of attention to a “venous quality”, one that receives information and traces thoughts as they travel from the periphery to inform our centre. In other words: We leaned into walls, then let walls lean into us. We pushed into the floor, then let the floor push into us. We touched others, then let others touch us. We danced, jumped, lay, listened, leaned. We reflected in Hundreds (Berlant & Steward 2019). One participant wrote:

Bloody ocean – bloody veins

Streams

Leading to extremities.

Stretching out far

And returning to centre.

Renewed. Re-formed

By each breath inside,

Each breath outside.

We dance. We touch. We move into waves.

We sing with voices

Not stoned by fear –

Not alone within our skins.

We really want this

And the castles of the words tremble –

For seconds, even minutes at a time.

Beings. Branches. Grasses.

Winds and fires.

We shed one skin

After the other.

Oceans of blood. Rivers of bones.

We stretch our arms. Stretch them further.

We jump out of standing

And into Under-

Wonder

(C. Lanken)

Cite this article as: Brendtner, Fine. June 2023. “Moving with Blood – an Experiential Anatomy for Thought”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

A Leap into a Practice of Embodied Thinking

Sigríður Þorgeirsdóttir

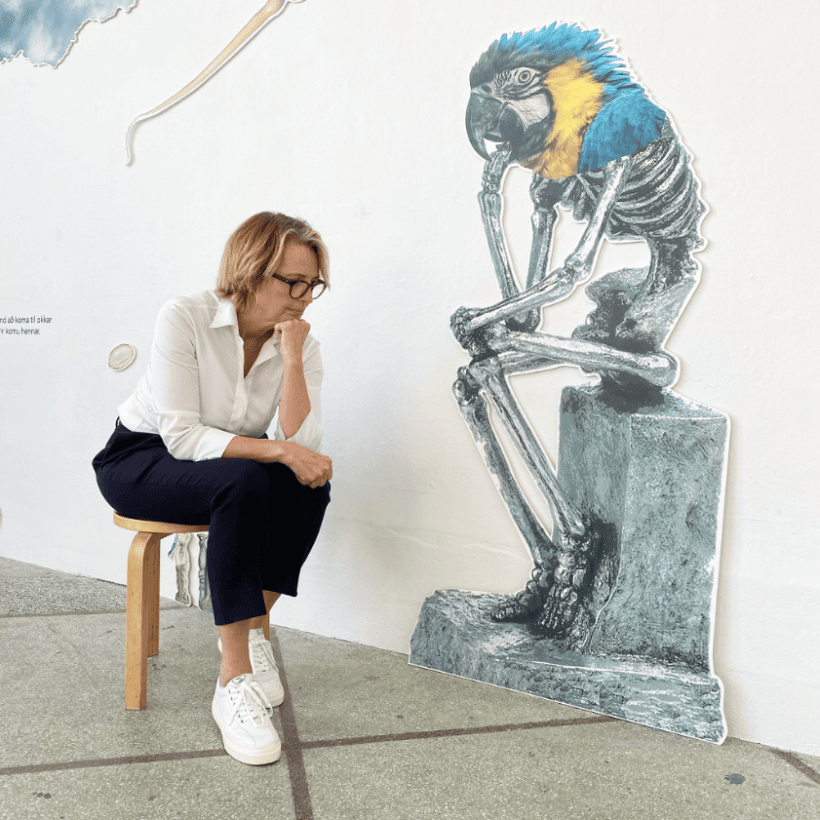

This is a photo of myself in front of a picture of “The Thinker”. The artwork was one of the pieces that Katrín Ólína did for a philosophical art exhibition, MINISOPHY, which we did together in Reykjavík in 2020. As a parody of Rodin´s emblematic sculpture of philosophical thinking, “The Thinker” is here portrayed as a skeleton with a parrot´s head, displaying scholarly discourse that has become out of touch, repeating phrases and concepts in a parrotlike manner. Such a thinker is “lost in abstraction”.[i] This image of the thinker parodies the cliché-image of scholars who use concepts and theories as if they were playing a game of cards that they have learned to play effectively and self-assuredly, and yet there is a hollow tone to their speech, as if a cultivation of a connection to their own living thinking is somehow missing.

Major schools of contemporary philosophy, be it analytical, phenomenological or feminist/queer philosophy, have emphasised how thinking for oneself is the core of philosophical thinking because philosophy is the type of thinking that is at the same time highly individual and universal. The philosophical in philosophy consists precisely in forging a link between a thought that has a source in the person –the acquired knowledge they possess through experiences, learning, language, and socio-political positionality– and a generalisation of that thought into universal, abstract concepts or general principles that express a problem or describe an actual phenomenon that is theoretically relevant. Scholars and scientists operate in a similar manner insofar they are the source of the questions and the themes they chose to research with the distinct methods of their disciplines, be they empirical, analytical or hermeneutical.

Insofar philosophers have themselves as a source of reflecting topics, issues, phenomena and problems, they are kind of their own laboratory. Philosophical reflections cannot only consist in combining positions, abiding by rules of logical coherence that yield a conclusion, an argument, a thesis. Such a process of philosophical thinking would amount to a mechanical, formalistic conception of it, and it would not accommodate the truly philosophical and scientific which is to shed some new light on a topic and conceptualise something in a fresh way that shows limits of previous positions or discloses new perspectives and potentials of them in order to increase understanding and carry knowledge forward. Innovative thinking has always consisted in unsettling habituated patterns of the logical, making it more logical, and in redefining concepts or inventing new ones.

But something is missing. Like Claire Petitmengin writes, the “scientist´s body” is “at the source of meaning” leading her to develop micro-phenomenology as a methodology to access lived experience through in-depth interviews and as a source of knowledge that is relevant for scientific research (2016). The philosophically thinking subject is neither purely neutral, generic, objective nor is it reducible to its socio-cultural determinants. In order to account for novelty or freshness in philosophical thinking we need to have a concept of a first-person perspective that is both socially situated and individual in thinking. It is embodiment that is the juncture of the social and the personal because each and every body is differentially situated historically, culturally, socially and represents a unique perspective. It is therefore embodied thinking that can account for the unique perspective that is the source of philosophical reflection while at the same time being socio-culturally situated. Embodied thinkers occupy a position of the practice of philosophy that unites an embodied source of thought and the ability to generalise it in abstract terms in accord with the context of philosophical styles or schools out of which they philosophize.

Cognitive sciences confirm that thinking is embodied, embedded, extended and enacted (Schoeller and Thorgeirsdottir 2019). Yet, what implications does that have for the practice of thinking embodied in an individual, non-neutral and contextual way? In the last few decades philosophers have begun to develop practices and methodologies of embodied thinking. These methodologies are still marginal in mainstream schools of Western philosophy. Methodologies of embodied thinking are hence the missing link for it is not enough to know, research, write and talk about the interplay of cognition and affect, mind and body. One also has to take the leap into the practice of embodied thinking by practicing methodologies of embodied thinking.

Methods of embodied thinking as well as insights of humanistic psychology contribute to an innovation of the practice of contemplative dimension of philosophical thinking.

It is a challenge to describe a practice for someone who has not had an experience of it even though this practice is something that has always been part of any thinking that we label as original, creative, to the point, precise, etc. Contemplation has always characterised what we call deep and profound thinking, but it is the new cognitive sciences that have made explicit how embodied thinking as philosophical contemplation functions as a certain experience of thinking. Methods of embodied thinking as well as insights of humanistic psychology contribute to an innovation of the practice of contemplative dimension of philosophical thinking. Methodologies of embodied thinking such as Eugene Gendlin´s “Thinking at the Edge” (Gendlin 2004) and microphenomenological methods envigorate the core of the ability of thinking for oneself, of finding meaning and sense in relation to an experienced world, and not just re-iterate topics of an established discourse. These are methodologies for theorising that approach the body of the researcher as doubly charged: with the potentials for sensitizing itself to the theory it already carries and for returning life to theory. The methodologies of embodied thinking “build the body of theory”. The phrase “building the body of theory” is then in the context of embodied critical thinking not a metaphor but points to an actual stretching and thickening of thought and articulation of theory transpiring through methodologies of embodied critical and creative thinking.

Our research project includes a training program for embodied critical thinking. However on a more artistic note, for the MINISOPHY exhibition mentioned at the beginning, Katrín Ólína and I have put together exercises that are meant to evoke embodied reflection about everyday things and phenomena. Here are two of them, one on breathing and another one on something as mundane as an ordinary rock.

An ordinary rock shows you that the mundane can be interesting.

Think a moment: A rock is neither bored nor expects it anything. A rock just is in the now. Not burdened by the past, nor anxious about the future. The most profound philosophy builds on the simplest of ideas, far simpler than we normally think.

Take a moment: Adopt this rock-solid attitude today. Check if something you may view as plain or uninteresting, like a very ordinary rock, has something important to tell you.

The breathing person suggests that you know that a person’s breathing says a lot.

Think a moment: The soul has in philosophy always been associated with breath. All living things breathe and the quality of one’s breath is a basic expression of life.

Take a moment: Notice how the other person you are talking to breathes. Fast, slow, agitated or calm? Observe how the breathing and the content of what they are saying are related. Are their thoughts alive? How are their breathing and what they say connected? Breathing with your whole body helps you think more fully.

Cite this article as: Sigríður Þorgeirsdóttir. June 2023. “A Leap into a Practice of Embodied Thinking”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Footnoot

[i] Thanks to Anne Sauka for this term of “lost in abstraction”.

References

Bainbridge Cohen, Bonnie (1993). Sensing, Feeling and Action: The experiential anatomy of Body-Mind-Centering. Contact Editions.

Ballestero, Andrea & Brit Ross Winthereik (eds). 2021. Experimenting with Ethnography: A companion to Analysis. Croydon: Duke University Press

Barad, Karen. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham & London: Duke University Press

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham & London: Duke University Press

Berlant, Lauren and Kathleen Stewart (2019). The Hundreds. Duke University Press. Durham.

Csordas, Thomas (1993). “Somatic Modes of Attention.” Cultural Anthropology 8 (2): 135-156.

Brandel, Andrew & Marco Motta. 2021. “Introduction: Life with Concepts”. In Brandel & Motta Living with Concepts: Anthropology in the Grip of Reality. New York: Fordham University Press.

Gendlin, Eugene. 1981. Focusing. New York: Bantam Books.

Gendlin, Eugene. 2004. “Introduction to ‘Thinking at the Edge’”, The Folio, 19 (1), 1-8,

Guyer, Jane. 2013. “‘The quickening of the unknown’: Epistemologies of surprise in anthropology” (The Munro Lecture, 2013). HAU 3(3): 283–307.

Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575-599.

Høybye Terp, Mette. 2013. “Healing environments in cancer treatment and care. Relations of space and practice in haematological cancer treatment.” Acta Oncologica, 52 (2): 440-446.

Hastrup, Kirsten. 1999. Viljen til Viden. En humanistisk grundbog. København: Gyldendal.

Latour, Bruno. 2014. “Sensitizing”. In Experience: Culture, Cognition, and the Common Sense, edited by Caroline Jones, 315-338. MIT Press.

Le Guin, Ursula K. 1985. ”She Unnames Them”, The New Yorker: 27-28.

Mattingly, Cheryl. 2019. “Defrosting concepts, destabilizing doxa: Critical phenomenology and the perplexing particular”. Anthropological Theory, 19(4): 415–439.

Myers, Natasha. 2014. “A Kriya for Cultivating Your Inner Plant,” Imaginings Series, Centre for Imaginative Ethnography.

Petitmengin, Claire. 2016. “The scientist’s body at the source of meaning”. In Thinking thinking. Practicing radical reflection, edited by V. Saller & D. Schoeller 28-49. München: Verlag Karl Alber.

Pratt, Mary Louise. 2007. “Introduction: Criticism in the contact zone”. In Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (2nd ed.), 1-12. London: Routledge

Smith, Aja. 2022. “At the Edge of the Sensible: An Argument for Staying with the Trouble of Doubt”. Ethos 49 (3)

Schoeller, Donata and Sigridur Thorgeirsdottir. 2019. “Embodied Critical Thinking: The Experiential Turn and its Transformative Aspects” philoSOPHIA: A Journal of Continental Feminism 9(1): 92–109.

Taussig, Michael. 2009. What color is the sacred? Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Yusoff, Kathryn. 2013. “Insensible Worlds: Postrelational Ethics, Indeterminacy and the (k)Nots of Relating”. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 31(2): 208–226

Featured image by Clara Fuglsbjerg Ebberup.