Introduction: Writing Hundreds, Exercising Thought

Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård

A text becomes when it is read. Its becoming may even be experienced as an event (Rosenblatt 1964). However, the writer may be the one who reads, the reader the one who writes – the reading-writer may be the one who witnesses her own writing and experiences the becoming of the text as an event. What then is the role of other readers when they read the reading-writer’s text?

When reading the three texts of this, the first section of Building Bodies for Thought, the reviewer, Trine Brinkmann, came exactly to such questions about her role as their reader – an uncertainty that was not least caused by the sections’ three authors’ diverse use of Berlant and Stewart’s method and format the hundreds (2019). Hundreds are texts that are exactly 100 words long – or multiple sets of 100 words long texts, as Berlant and Stewart’s book The Hundreds showcases through a compilation of their own hundreds. In their work hundreds seem to both work as an analytical tool and figure as poetic analysis of the world. But in the hands of other thinkers, the hundreds may come to work and figure also in others ways – as is the case in this present section.

As Brinkmann put it some of these hundreds seemed illustrative of a mode of embodied thinking “that leans into the indecisive, troublesome, messiness of things”. Other hundreds rather seemed to serve to order related kinds of messiness – and as such perform as a method for turning unruly experience into rhythm, flow and argument. Others again seem to use the kind of seductive, aesthetic order which the rhythm and flow of hundreds induces to embrace and as such, in Brinkmann’s words again, stay “truer to mess”. We propose that you read these three texts exactly for such diversity; for their heterogeneous assembling of bodies, writing and thinking.

We begin with Vanessa Graf, for whom writing hundreds in itself is an activity of thought; her two hundreds bear not necessarily any connection or relation to one another, only by virtue of the function they serve as vehicles for the development of ideas. Hundreds are, for her, a discernment or thinking-through-writing that draws on the body in a search for an intuitive order of things as she lets “ideas simmer and brew” until they are “ready to be expressed with a word, a phrase, a paragraph” (Graf this thread). Here the body is one that walks, sits, explores a plant, allowing movement-touching-thinking-writing to together create rhythms and spaces for new thoughts.

In Ida Appel Vardinghus-Nielsen essay, she shows how hundreds may work as a phenomenological epoché – a suspension of judgement. Sparked by a plant-sensing experiment (Myers 2014) that inspired a sensation of roots emerging from the soles of her feet and deepened by way of a ‘focussing’ session (Gendlin 1981), the writing hundreds further sharpened her sensory perception and increased the attentiveness of her body. Returning to the plant sensing-thinking-writing experiment a second time, it all transpired ‘more smoothly’, as if her body’s alertness had indeed been strengthened. Here, a body of sensation and intuition, is drawn forth and made noticeable for both writers and readers.

Lastly, in her characteristic subtle style, perhaps with a slight touch of grief, Kathleen Stewart describes how, when writing together with The Hundreds’ co-author the late Lauren Berlant, “[t]hought was a muscle flexed in the elaboration and fabulation of what was already textured, angled, composited” (Stewart this thread). We hear about leaning into silences, about getting to the precision of the thing and about all that which falls in between. Here, the hundreds was a body of thought exercised in the contact between bodies.

When reading across the three texts in this section, you may as Brinkmann did, get as much “a sense of embodied writing”, as you get “a sense of bodies that are writing, and of written words turned into bodies”. It is as if the three texts bear witness to different states of mind; we are shown snap-shots of ways of thinking, are allowed to finger the very fabric of different thought processes and are in the end left to ponder our own thinking and how it figures in our writing.

In a reflection of and paying respect to the collective nature of thinking, we have chosen to cite central aspects of the reviewers comments in each section. We hope that this openness shall inspire conversations to continue beyond the thread – beyond this present thinking.

Cite this article as: Smith, Aja and Anne Line Dalsgård. June 2023. “Introduction: Writing Hundreds, Exercising Thought”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Academic Fictions, Fictitious Academics: Writing in Hundreds

Vanessa Graf

I met you at the end of days. You said it was cancer, though I thought it might have been the new industrial complex they had built next to your home a few years before, but it did not matter and so I sat and said nothing. You told me that you were not scared and I said that I was glad about that. You were climbing a leaf and I saw you crawling, your big bug eyes so scared, so when I reached out to crush you, I tried to be quick: You were the last of your kind.

This hundreds (the first hundreds I ever wrote), I simply thought of as a story: A self-contained narrative, told in a hundred words. It did not have to follow any other structure, or fit a certain format, nor did it have to fall clearly into any categories. Academic writing? Scientific article? Letter, poetry, literature, fiction? No matter, as long as it did not exceed or fall short of the word count. The instructions left out more than they specified: Do not be concerned with references, they said, don’t overthink. Simply choose a situation, an experience, or an encounter, and write.

This is easier said than done, and so my notes app filled with fragments of sentences over the following days, none of them finding an easy connection to the next. The chaos of my notes reflected my preceding days’ conversations at the time, about storytelling and speculative fabulation as ways of navigating and imagining the climate crisis. Extinction, ecologies, holobionts, and mushrooms – they all met in the fragments of my notes, a weird and wonderful assemblage of arts (and sciences) of living on a damaged planet (Tsing et al 2017).

The words that came into my head did so without first announcing their presence; they popped up as if out of nothing and I hurried to write them down before they vanished again. I did not think about them or try to make ideas fit a written frame, I did not strive towards coherence, nor did I actively choose a topic. Writing the first draft of my first hundreds was subconscious more than anything else, a bodily experience: letting ideas simmer and brew until they were ready to be expressed with a word, a phrase, a paragraph. My first hundreds was a condensation of thoughts and concepts exchanged, heard, and discussed in the two previous weeks; an almost spontaneous expression of thought processes that usually run in the back of my mind, unnoticed.

It remained in this unfinished state until a few days later, when I went on a walk and came upon an abandoned lot. It used to house part of a train track, behind a building which is currently a supermarket, and the unused space is now overgrown with wild herbs, littered with cigarette butts and empty beer bottles. I bent down to examine a plant I had not noticed before, and a sentence ran through my head: I met you at the end of days. I met you at the end of days, and all the words populating my notes app made sense, I met you at the end of days, and the rest of the hundreds all but wrote itself.

Since then, I have started to write hundreds whenever I need to discern a thought that has quietly been forming in the back of my mind, but so far has eluded any formalisation. Part fiction, part philosophical ideation, the hundreds provide me with an opportunity to step outside the tight constraints of academic writing and let my mind run free. They do not have to follow logic, form arguments, or interpret data; rather, they let me follow intuitions in a way that usually only fiction writing allows me to do. Like in that first attempt of writing a hundreds, the method acts as a vessel for the ideas, concepts, contexts, and inklings that are brewing in the background, out of focus – articulating what otherwise I could not (yet) have expressed. I see this process when I read back my hundreds now: Although they may appear to be ordered, a story neatly contained within itself, the words transport me to times in my research process where I was struggling, searching, questioning.

When I write hundreds, I write with a rhythm: There is a certain flow to the words, an intuitive order of things that, again, reminds me much more of fiction than it does of academic writing. Where usually I would write with the mind, ordering and structuring my words, in the hundreds (as in fiction), I write with the body. Priorities shift and perspectives are sharpened, nuances are introduced, and shades of gray become discernible. The practice of writing hundreds in an academic context exists in an in-between where rules are suspended, and certainties dissolved. They are thinking-through-writing, and as such they open space for discomfort and inquisitive questioning. They are wild and varied and nonsensical and informed, they are everything and nothing and all of them are different, except for one aspect, of course: They are composed of a hundred words.

They thought it was weird when they found it, and everyone they showed it to agreed: How strange, how vast, how infinitely beautiful to be connected to everything and everyone all at once. A team came in to prod it and define it, somebody offered a name and then a tag, but the thing that stuck was nothing like it ever sounded. A man named Paul sat down to draw some dots, filled in the lines, and was left with three shapes. Let’s choose this one, they said, that’s what it will be, the most secure: Let’s call it Cloud.

Cite this article as: Graf, Vanessa. June 2023. “Academic Fictions, Fictitious Academics: Writing in Hundreds”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Sustaining the Experience of Difference

Ida Appel Vardinghus-Nielsen

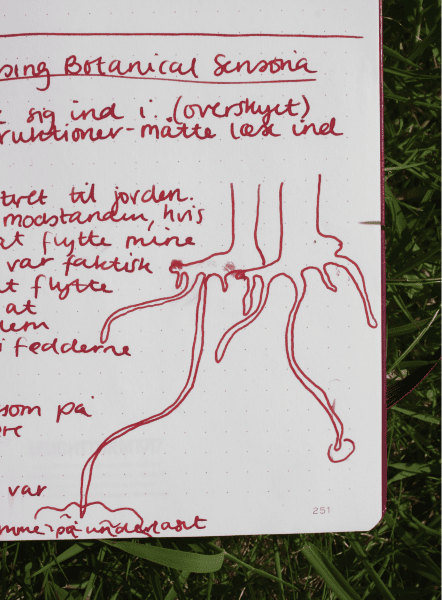

As a budding anthropologist with limited experience of participant observation I began exploring the alertness and range of my senses in my living room. I was guided by Natasha Myers’ (2014) text in which she offers entry points to imagining the different sensorial experiences of a plant, an exercise that supposedly helps sharpen sensory perception and increase the attentiveness of your body. And so, I stood in my living room, trying to grow leaves and dig my roots into the ground – meanwhile doubting that I was doing it right. How was I to feel a physical experience that in concrete material terms was not taking place? Nevertheless, I was surprised to feel roots growing from the soles of my feet and became fascinated with how far plant senses may reach.

This exercise was part of a course in my master’s degree in which I was also introduced to the Lauren Berlant and Kathleen Stewart’s method of writing hundreds (2019). Based on this I was asked to try to capture the experience of my sensorial engagement with plants through the act of writing hundreds: exactly one hundred words centred on the affective aspects of this exercise.

I was a plant. I dipped my root into the tiny underground pool. With uncertainty, I understood that plants have their own sensuousness. So many contact points. A few days later I was looking at some big trees, their leaves were thrown around by the wind. The trunks stood completely still. Is it nice to shake like that? The wind also blew through my hair; we’re shaking together, I thought. But do we experience the same? I think about usefulness, function. What do they gain from shaking like this? I don’t ask – What do I gain from shaking like this?

Writing hundreds drove me back to the experience and made me inquire into it. What stood out was not doubt about whether I was doing the exercise correctly, but a fascination with the sensorial world of plants: I had started noticing trees, acknowledging their individual lives and experiences. This unexpected impact of my bodily engagement with plants only became clear when I began to write about the exercise and couldn’t help but include the experience of swaying with trees in the wind.

I was fascinated with this new world yet, at the same time, I realized that I might never come to understand it fully. Dalsgård (2018) describes a similar situation as a moment of epoché: a moment of becoming aware of one’s body in a way that calls attention to the difference in experience between oneself and the other. It is a bodily experience; it comes before any analysis. Actively creating the conditions for such moments to arise requires training, as does the ability to trust them as significant. I had many feelings in the moment of the exercise: doubt, attentiveness, imaginative sensorial impulses, and the smells, sounds, and temperatures of my immediate surroundings. How does your body learn to recognise nuances and patterns within this amalgam of impressions? By writing hundreds I noticed how I felt; I thought about what the trees felt and wondered how it was different and similar. It was only when I had to describe my sensory perceptions that I reflected on the extent to which I had tapped into a plant’s perspective – and, further, how my sensory dispositions affect how I ask questions about experience. Guided by what my body might already have known, writing helped me order the experiences and find patterns in cacophonic sensorial impulses. This revealed a gap between experiences. In this sense, writing hundreds sustained the subtle feelings of difference and made it possible to interrogate them, leading to new insights about the uniqueness of plant senses and the way my own senses shape and effect knowledge.

Returning anew to the exercise of expanding my senses through engagement with plants and writing, I came to experience and explore the interconnectedness of different beings in a forest:

Soft orange warmth and comfortable coolness. I’m at the mercy of the sun and shady entities. I’m grounded, but I can rustle, absorb, grow, and breathe. I’m never alone. Around, in, and on me are the sun, ants, larvae, and birds. The bird aids me by spreading my seeds, but it also has its own agenda. Its nest rests on a branch close to my trunk. And that’s okay, it’s nice, even though it doesn’t serve my purpose in itself. But still, it has everything to do with me. I’m never without the forest. I do not control my connections.

Experiencing epoché-like moments also entails letting the other world challenge your own perception and assumptions (Dalsgård 2018). Exploring connectedness within the forest made me think about my connections. How might I also be at the mercy of something? Although it sparked a search for similarities, this change of perspective upon my own existence came from a feeling of difference. I generally consider my body as bounded and my being as autonomous. Do I feel different from the tree because my idea of personhood blurs some of my connections? These types of questions came more smoothly this time around. My first attempt at writing hundreds had filtered out some of my concerns about ‘doing it right’. This meant that other sensations could come to the fore.

Constrained by the hundred-word limit, I was forced to be precise and think about how every single word articulated and captured my experience. This process drew out and sustained my feelings of difference and provided an opportunity to notice these feelings with more attention than was possible during the practice. When repeating the exercise I felt the effects, albeit small: greater calm and an enhanced sensuous attention towards the gaps between experiences. In this way the circular movement between experimenting with the range of my senses and hundreds trained my body’s alertness and my ability to notice my sensorial predispositions in the moment.

Cite this article as: Vardinghus-Nielsen, Ida Appel. June 2023. “Sustaining the Experience of Difference”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Flexing a Muscle

Kathleen Stewart

For Lauren and I, working collaboratively, The Hundreds was a mode of being in condensation and drift. A thought exercised by contact. We came to points and moved away again, playing with associations, cutting words to get to the precision of the thing about a birthday cake in a scene or what seemed to be happening in the end-of-shift talk on a city bench, the posturing of tired butts.

Thought was a muscle flexed in the elaboration and fabulation of what was already textured, angled, composited. We leaned in, extending to catch something still coming from different directions at once in a quiet hotel corridor or the sensation of waiting.

I became protective of the strange potentia in all worlds.

Lauren demanded a searing empathy for all the human fuck ups.

In the collaboration, there was anxiety, rawness, some pushing –“What do you mean by that? Where are you?” We were a subject’s plastic contortions pulled onto a track for a minute and flailing. We held hands, or withheld, in the surprise negative space of contact points, detours, a change in register, a refrain stretching across modes.

Phone calls started with a frank toe poking into the water of the other to feel out the contours and fractals of some world dinging them, the words they were coming up with, the sonorous compositional field they had entered. Through ins and outs we revved up to the threshold into the sharp or the hilarious; the riff of a sentient mind was a heaven built on worldly bits.

Lauren was a race horse chomping at the bit.

I was impassive in an exposure to the noise and wind of what was at hand.

Between us, things muscled through. We flexed lines of response by thinking with rhythms and tones, characters and benches. In between the ‘us’ and the ‘it’, between looker and object, minor keys roosted beyond critique’s rough handling – not just reason’s leftovers, not the imperceptible, insignificant, marginal, micro, or beyond language but the cul de sac of a meanwhile, the fake fundaments of what hardened up for some, the sloppy dissolution of a public memory, a homing, an energetic entrapment or release.

Editing under the warm constraint of one hundred words, we were tight with words and events; they became the material and aesthetic medium of thought. We built our chops on the incidental or the actuality of a snowflake; we knew we were lucky to be grasping at things that didn’t just add up. A privileged seat at a distant table was not where we wanted to end up.

Pulling into rickety alignment with things, we skirted the edges of what transed and skewed, the excess in an awkward swipe. We felt the capacities in a gesture still verging, a look lingering for no known reason. We saw the improvisatory conceptuality in a colour or the quality of the sun.

Writing, like any practice of living, became not just a routine act but the tendon of a tendency. We stayed with what couldn’t just be explained in a vie for clarity or a vote for face value.

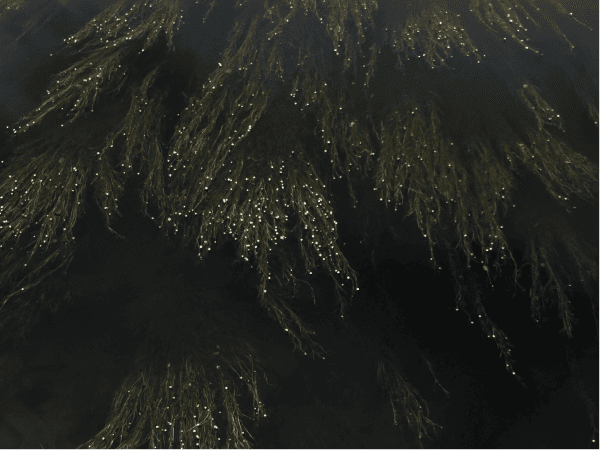

Writing with the nervous system of prolific and shrinking worlds taking place in fits and starts was a nimble repositioning, transportive and differently attuned to remnants, the disappearance of a tiny snow bird, the activations and deactivations that hummed in the background of a scene, everything that was wasted in a missed opportunity or a sharp extraction, the prism of things actualized, corrupted or unrequited. We waited for eddies twisting off an edge; we tried to catch up with what was already mired in a shoulder shrugged.

We wrote for what happened between the immediate and what gets abstracted. We worked in parallel with each other as readers and with all the its encountered without quite touching or owning anything. We quickened at a passing glance or an entanglement folding back on itself.

The object of exercised thought was a sounding we learned to make, a glimpse we tried to catch; the lily pad of a quick landing and a bounce in a speculative impersonal world of loss and generativity.

Cite this article as: Stewart, Katleen. June 2023. “Flexing a Muscle”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

References

Berlant, Lauren and Kathleen Stewart. 2019. The Hundreds. Durham and London: Duke university Press.

Dalsgård, A. L. (2018). “Feet on the Ground: The Role of the Body in Pre-Textual Ethnography”. In Pre-textual Ethnographies: Challenging the phenomenological level of anthropological knowledge-making, 25-39, edited by Rakowski, T. & Patzer, H. Sean Kingston Publishing.

Gendlin, Eugene T. 2003 [1978]. Focusing. How to gain direct access to your body’s knowledge. London: Rider

Myers, Natasha. 2014. “A Kriya for Cultivating Your Inner Plant,” Imaginings Series, Centre for Imaginative Ethnography.

Rosenblatt, Louise M. 1964. “The Poem as Event.” College English 26 (2): 123–28.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Heather Anne Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt (eds.). 2017. Arts of Living on a damage Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene