In what follows, Silva disentangles “the standard and universalising mode of liberalism” (11) from its vernacular counterparts. The broad arc of his argument is that liberalismo (the Portuguese equivalent of liberalism) and liberdade (a colloquial/emic Portuguese term that encapsulates notions of both liberty and freedom) be considered distinct from and at par with Euro-American, normative liberalism. By doing so, he asserts that liberdade is not an adaptation of normative liberalism. He also salvages vernacular liberalisms from the anthropological critique of Euro-American liberalism’s colonial origins and effects. This crucial departure from contemporary work on liberalism rectifies a regrettable oversight. If the trend has been for anthropologists to avoid studying liberalism because they “fear an alignment with normative liberalism” (188), this book boldly seeks to reverse it, drawing a distinction between anthropology with a normative liberal bias and the critical anthropology of and for liberation.

Silva disentangles “the standard and universalising mode of liberalism” (11) from its vernacular counterparts.

Yet, one might ask, why study liberdade in relation to hegemonic, normative liberalism in the first place if it is indeed a politics and a practice in its own right? The distinction Silva draws between liberdade and normative liberalism is not as straightforward. The public in Rocinha do not celebrate normative liberal values. Nor do they outrightly reject notions of freedom and liberty. A third form of engagement, the one Silva argues he found within Rocinha, entails neither acquiescence nor rejection, but rather working on the exclusionary forces inherent to normative liberalism and “transforming” them for the purposes of people in Rocinha (188). Silva conceptually frames this engagement by drawing on queer theory and performance studies, in particular José Esteban Muñoz’s work on disidentification.

The strategy of disidentifying with normative liberalism allows Rocinha dwellers to articulate numerous non-normative vintages of liberalism. Silva refers to these as minoritarian liberalisms, which include “favela liberalism, queer liberalism, peasant liberalism, maroon liberalism,” (12) and so on. He outlines three characteristics that define minoritarian liberalisms. Firstly, they differ from normative liberalism in that they do not share in the latter’s tendency to impose universal standards (as such, they deterritorialise the field of liberalism.) They are espoused by groups that occupy a potentially subversive position in society vis-à-vis dominant groups. Secondly, minoritarian liberalisms substitute a more “collective mode of politics” (13) for normative liberalism’s individualism and nation-state centrism. Finally, exploring minoritarian liberalisms involves, among other things, “creating ever more radically mutant modes of freedom” (21), which are traced onto varying everyday experiences of liberty and freedom, and are enabled by unique material circumstances. As such, minoritarian liberalisms expand the ways in which subjects can be free.

His conviction that freedom be understood as a practice expressed in, for instance, bodily form led him to “trace some of the concrete operations of freedom”.

While the questions raised in the book might appear philosophical, Silva’s strategies for answering them remain decidedly ethnographic and rooted in lived experience. His conviction that freedom be understood as a practice expressed in, for instance, bodily form led him to “trace some of the concrete operations of freedom” (18). This involved taking note when vernacular Portuguese terms for the concepts of liberty and freedom appeared in everyday speech, then unpacking the empirical context in which those words derive their meaning and the significance those words lent to speakers’ actions.

Silva confronts his positionality at several moments in the book, for instance in relation to how “not being heterosexual was critical to facilitating [his] relationship with Natasha and others in the favela” (11). At the same time, he leaves the reader curious about the relationships his positionality precluded. This repeatedly appears to be a significant aspect, from when he received criticism from his neighbours for hanging out in a “morally degraded” part of Rocinha, “a zone of double abjection” (98), to some unappetising interactions in the Brazilian hinterlands (78-79, for instance). To his credit, Silva does a commendable job throughout the book of laying bare his preconceptions (see 42 and 112), as well as reflecting on how his initial plan to study the limits to freedom in Rocinha influenced what he was able to learn during his time there. Extended a little further, his perceptiveness regarding the relationship between his identities and the connections he made (but also did not make) in Rocinha could have given readers a richer, contextual understanding of minoritarian liberalism, especially in relation to the presence hegemonic liberalism within Rocinha itself.

As it appears in Minoritarian Liberalism, normative liberalism seems almost to be a caricatural foil.

By its own admission, the book can propound a rather flattened conception of normative liberalism at times. One strategy to avoid this could have been to better parse the various possible aspects of life in which liberal values can be championed — economic, socio-cultural, political — and map out which vintages of liberalism concern themselves to what extent with each of those aspects. As it appears in Minoritarian Liberalism, normative liberalism seems almost to be a caricatural foil. This is hardly a demerit, since Silva does not profess to have written a book about normative liberalism, quite the contrary. Nonetheless, it might be a hiccup for readers more fastidious about political theory, and blunts the force of his argument at times.

Minoritarian Liberalism is a pleasure to read and advances anthropological scholarship and the craft of ethnographic writing. It draws on various current debates and interestingly pulls together a range of theorists and scholars that have not always been in conversation with each other. The book convincingly argues in favour of reconceptualising liberalism, vindicating the experience of freedoms and liberty at the margins of society not only from the universalising effects of hegemonic forms of liberalism but also from overzealous scholarly critiques of liberalism writ large. Further, it initiates, rather revives, an important conversation, pointing readers in directions that, while beyond the scope of this book itself, require further inquiry. What explains the universalising tendencies of hegemonic forms of liberalism? Are non-hegemonic variants of liberalism minoritarian by virtue of the socio-economic standing of their proponents or by virtue of their internal logics alone? How can we push further an approach centred on understanding freedom and liberty as practice and how could such an approach better articulate with an understanding of liberalism as a political ideology? In provoking these questions, Minoritarian Liberalism marks an important advance in a vital broader conversation.

Reference

Lino e Silva, Moisés (2022). Minoritarian Liberalism: A Travesti Life in a Brazilian Favela. University of Chicago Press.

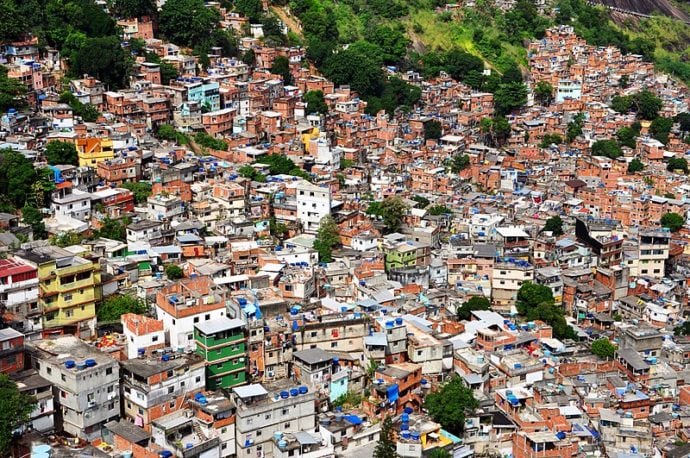

Featured picture by chensiyuan, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.