“I can only work cash-in-hand [načerno] for the rest of my life,” Nina[1] told me as we were sitting in her kitchen drinking black coffee while she was rolling cigarettes from tobacco purchased in half kilogram packages. Her partner Ivan had left for his afternoon shift at Clean, a municipality-owned company responsible for maintenance of public spaces in central Ostrava and the district of Údol. Nina was a 46-year old resident of Údol, a neighbourhood stigmatized as a “Gypsy ghetto”, whose house I frequented between June and December 2016.

When I started visiting her house a few months into my fieldwork, our conversations evolved around my attempts to find odd jobs. Nina was very helpful in advising me where to look, and where to get the fit-for-work certificate and other required paperwork. She herself was unemployed. I sometimes tried to reciprocate by sharing job openings with her, until she one day matter-of-factly clarified that the size of her debts rendered any pursuit of formal employment pointless. Due to debt payroll deductions, her monthly income would be lower than what she received being on benefits and occasionally taking cash-in-hand jobs without a contract. She estimated that her debt instalments would come to about 9,000 CZK per month (313 GBP), depending on her gross wage, which would be around 12,000 to 20,000 CZK (417 to 696 GBP).

Nina was not entirely sure about the total amount she owed. During one of our first conversations regarding this issue, she said her debt was over 300,000 CZK (10,400 GBP). Later she told me she thought her debts were likely to be much higher, perhaps up to 1,000 000 CZK (35,000 GBP). They resulted from unpaid T-mobile bills, unpaid public transport fines, consumer credit, and loans from non-bank institutions.

Despite the stigma built around the trope of “excessive” spending by the Roma community and their supposed lack of consideration for the future, the pathways to indebted lives that I observed had little to do with culture and a lot with the operation of capital.

The debt industry grew its own market with companies buying outstanding debts from lenders and enforcing debt claims inflated by additional fees. This practice continued despite an acknowledgment of the Czech Ministry of Interior in 2008 that companies buying and reclaiming consumer credit were poorly regulated and frequently enforced debt claims without court orders. Most of the debts claimed from my informants were handled by such intermediaries rather than by public authorities (in cases of arrears) or lenders (in cases of credit).

A significant source of debts among my informants were various forms of non-payments: failures to pay transport fines; a failure to pay alimony after separation from a partner; non-payment for waste collection or utility bills; non-payment of compulsory health insurance during times of unemployment. Out of these, non-payments for waste collection became widespread after the city council stopped sending invoices and those who did not have a direct debit set up incurred arrears. The effect of these debts on lives such as Nina’s are profound and long-term. Private bailiffs enforce debt claims from those who have income from wage labour but also from pensioners, women on maternity leave, or other persons on welfare benefits. For example, Nina said that six years ago her maternity leave, which was about 7,000 CZK (246 GBP), was reduced every month by 1,800 CZK (63 GBP) of her T-mobile debt repayments. At one point, she was no longer able to repay her debt and her outstanding bill plus interests and fines for late payment continued to grow. In addition, she had arrears on water bills from a period when she lived in council flat in Údol. A direct consequence of her situation, in which she was no longer able to repay the debts from arrears, is a life predicament of working cash-in-hand. To get by despite low and irregular income, Nina is forced to further borrowing: money from local loan sharks; and food purchasing on credit from the “Vietnamese” corner shop (večerka).

The state or public authorities outsource enforcement of debt claims to private companies. This way the state becomes not only the entity responsible for the legal and policy framework for the debt industry but also its client.

A “promised land” for non-bank creditors?

When a family or an individual incurred unexpected expenses, or simply did not get by one month, they had to turn to credit. A solution that was supposed to be temporary turned permanent, and the deceptive advertising of non-bank institutions was a significant factor in this.

Observing the lives of indebted residents of Údol, I concluded that the operation of non-bank loans is characterized by fraud and the subsequent expropriation of racialized workers.[2] The experiences of my informants in Ostrava suggests that the changes in the 1990s and the introduction of labour and housing markets produced vulnerabilities that affected Roma in a specific way. Their employment options have been increasingly confined to certain jobs such as domestic cleaning, street cleaning, waste recycling or construction. Due to discriminatory real estate practices, their chances to access housing was limited to racially segregated areas, often with reduced access to services, shops and leisure facilities. Their educational opportunities consist of “Roma-only” schools and schools following reduced educational programmes.

In this context, non-bank loans for Roma represent a post-socialist equivalent of racialized hyper-expropriative “sub-prime” loans, which financial markets pushed on African-Americans and other people of colour. Over the past 20 years, the Czech Republic, along with other “post-socialist” countries in the region have gained a reputation of “a promised land for non-bank consumer credit providers” (Kotous and Šimek, 2017). This was mainly thanks to minimal regulation of lending provided by financial institutions other than banks.

One of the features of the “non-bank loans” in the Czech Republic is that they offer loans without any collateral on a very high interest ranging from 20 to 300%. These loans are typically lower than 15,000 CZK (510 GBP) and are targeting clients on low income (Dotlačilová 2013). A relatively small credit taken from non-bank institutions (nebankovní instituce) can result in spiralling debt due to high interest. For example, Ivan borrowed 13,000 CZK (456 GBP) from SuperCredit several years ago and currently owes 150,000 CZK (5,259 GBP).

A poster about 1km away from Pěkná Street in an area with a supermarket, a hairdresser, a “Chinese” shop and a pub. The poster advertises consumer credit up to 10,000 CZK (316 GBP) and 0% interest during the first 20 months of repayments. What it fails to say is that annual percentage rate of charge is 24.7%, which means the consumer will pay these charges after the initial 20 months. Image by Barbora Černušáková.

A number of my informants said formal debts were the main reason why it did not make sense for them to seek a job in one of Ostrava’s industrial zones. One day in August, I was chatting to Robert, responsible for a crew of street cleaners employed through the Labour Office. In his early 20s, Robert said that he used to work in a “Korean company” in the industrial zone some years ago. His gross monthly salary of 17,000 CZK (595 GBP) was cut every month by 5,000 to 6,000 CZK (175 to 210 GBP) due to debt claims. So he left the job and started working in street cleaning, being on close to a minimum wage, but incurring lower debt claim payments. This was due to the practice at Clean of keeping the debt payroll deductions reasonable so that workers do not end up below subsistence level and eventually leave. This practice changed some months after I left Ostrava, when the company increased the payroll deductions as requested by the law, which reduced some workers’ incomes to the legal minimum of 6,178 CZK (216 GBP).

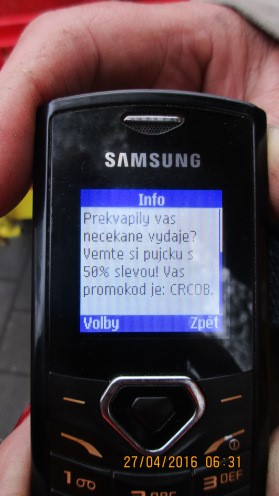

An unsolicited advertisement received by my colleague at the street cleaning company. The advertisement says: “Are you experiencing unexpected expenses? Get a loan with a 50% discount.” Image by Barbora Černušáková.

Due to hidden fees and rising interest, the actual debts by far exceed the amounts people borrow. Miss Teresa, an accountant at Clean explained to me that once there is a claim against a debtor, it includes daily interests. She was processing a payroll deduction of one worker against whom there was a debt claim of 20,000 CZK (700 GBP). The daily interest was 0.08%, i.e. 16 CZK (0.6 GBP). Since the debt in this case dated back to 2008, the interest increased the initial amount by 46,720 CZK (1,620 GBP), i.e. more than double the borrowed amount. In addition, a debtor has to pay also various “fees” associated with the repossession.

Julek had a secondary education and had worked for a moderate salary for over a decade. He grew up in an orphanage where he was exposed to the gajo [white] world, especially its cuisine. “I cook gajo food, so many Gypsies like to visit me and taste it.” Shortly after he left the orphanage in the 1990s, he became a victim of fraud. Somebody asked him to put his name under a fast loan application which he did upon agreement that he would get part of the money. “I may have seen up to 30,000 CZK (1,050 GBP) out the total amount.” His debts have reached about 600,000 CZK (21,016 GBP) because he did not pay them back and the interest kept increasing the owed amount. His monthly income is cut every month due to debt-related payroll deductions, which render it fairly low. He lives in a dark dilapidated one-bedroom flat in a run-down neighbourhood.

Because the Czech legislation does not cap the maximum interest rate, predatory lending is lawful. Lenders are free to offer money on high credit and with high (often hidden) fees. Although the burden of personal debts and the operation of the “repossession industry” (exekuce) in the Czech Republic has been criticised by the media for some time, activists and politicians, the system continues to favour the lenders and aggressively squeezes the debtors.

Bible v Bailiffs

Bailiffs visited Nina quite frequently. I asked her how they behaved during those visits. Like “assholes” (hovada), she said curtly. “They shout and threaten us.” One of the first things she stated in this conversation was that the bailiffs are white [gádže]. “They find out the dates when we receive benefits and come.” At one occasion, she would not let them in. The violent behaviour of bailiffs was also mentioned also during my conversation with Julek. He once accompanied bailiffs to a family in the neighbourhood of Údol. We both knew the family in question – they were Born-again Christians belonging to a group colloquially called ‘Hallelujah’. During the visit of the bailiff accompanied by Julek, the family members presented a Bible and started preaching to them to distract them from the purpose of the visit. “Good that I went to that visit,” noted Julek, otherwise he said the bailiffs would have used unnecessary force.

The experience with debt of Nina, Julek and others illustrates how home has become a new “frontier of accumulation” in a post-socialist city.

At the core of it is the ability of capital to extract profit from very low-income Roma households. What makes the transfer of wealth from the social margins to the core through the mechanism of debt possible is the state. Its legislation and policies create a framework in which indebted individuals and families become almost defenseless vis-à-vis the barely regulated operation of financial capital. In addition to this, the state also becomes a client of capital in the form of companies that claim debts from arrears on public services.

References

Allon, F. “The feminisation of finance: gender, labour and the limits of Inclusion”, Australian Feminist Studies, vol. 29, no. 79 (2014), pp. 12–30

Dotlačilová, L. 2013. “Vývoj zadluženosti domácností”. MA Thesis. Pardubice University. Available at: http://docplayer.cz/3415044-Univerzita-pardubice-fakulta-ekonomicko-spravni-ustav-ekonomickych-ved-vyvoj-zadluzenosti-domacnosti-v-cr-bc-lenka-dotlacilova.html

Fraser, N. 2016. “Expropriation and Exploitation in Racialized Capitalism: A Reply to Michael Dawson” Critical Historical Studies 3, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 163-178.

Paula Chakravartty and Denise Ferreira, “Accumulation , Dispossession , and Debt : The Racial Logic of Global Capitalism”. American Quarterly 64, no. 3 (2013): 361–85.

Kotous, J. and Šimek, D. 2017. “Consumer credit in the Czech Republic: from chaos to order”. Financier Worldwide. Available at: https://www.financierworldwide.com/consumer-credit-in-the-czech-republic-from-chaos-to-order/#.Wrfp5BiZPR0

[1] All given names and place names are withheld to protect the privacy of the people I met during my research.

[2] I am pursuing Fraser’s argument that racialized Roma workers are not merely exploited but are “expropriated subjects”, the cornerstone of “the dwindling ranks of protected exploited citizen-workers” (2016: 176).

Featured image by PublicDomainPictures (Courtesy of Pixabay.com).