Since the first week of August, hundreds of young Afghan asylum seekers have been holding a sit-down protest against deportation in central Stockholm. The protest is staged on the stairs of Meborgarhuset (the citizen hall) in Medborgarplatsen (citizen’s square). While the spatial connotation cannot be missed, the form of the protest could not be more expressive.

To sit down, to occupy a place, to be settled and immobile, is what Afghan people on the move desire and deserve.

Forced migration within and from Afghanistan is undoubtedly one of the largest and most complex examples of forced migration ever experienced by a single nation. A rough estimate shows that between 10 and 12 per cent of the whole Afghan population are displaced (either inside or outside the country). This rate is several times higher than the general worldwide rate of displacement, which is 3.3 per cent. For many Afghans, forced displacement has become protracted. Almost four decades of foreign occupation, civil war and disastrous environmental degradation have resulted in the destruction of large parts of infrastructure, the educational system, agriculture and industries. Accordingly, seeking a better life abroad is still the only option for many young Afghans. Along with Syria, Afghanistan was one of the top two source countries of refugees in the world in 2016, and the country of origin for the largest number of unaccompanied asylum–seeking children. In the same year, EU countries declared that 80,000 rejected asylum seekers will be expelled to Afghanistan. Moreover, over 1.3 million are internally displaced inside the country. The urgent question is not where people are deported to but to what they are deported.

Experience of deported Afghans is an experience of being expelled from Europe and being outcast in Afghanistan.

Many Afghan deportees are abandoned and left with no support from the moment of their arrival. I recurrently hear them commenting on their arrival this way: ‘no one was there’ [at the airport]. For many of them, deportation often means the forced return to a situation worse than the situation prior to the initial departure, politically, financially, and socially. Consequently, adjustment into the country of citizenship is usually uncertain and difficult. Opposite to the what European states attempt to show, the deportees do not go back home, but they re(join) a transnational space of expulsion, oscillating between re-departure and re-deportation.

There are multiple factors that make adjustment difficult, if not impossible, for the deportees. First, the majority of the Afghan asylum seekers in Europe belong to the Shia Hazara ethnic minority, who have historically been exposed to racial harassments and institutionalized discrimination by the powerful Sunni Pashto majority. Reports by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have documented systematic sectarian attacks targeting Hazara people by Taliban forces. Many Afghan deportees cannot return to their hometowns or villages due to armed conflicts. Travelling between cities has become so risky that the main road from Kabul to Hazarajat, the region inhabited by the Hazaras in central Afghanistan, has gotten the name ‘Death Road’. The deportees have to take great risks, sometimes greater than when they crossed the border between Iran and Turkey or across the Mediterranean Sea, to reach their village or town from Kabul. Moreover, four decades of armed conflicts have resulted in not only the destruction of physical homes, but have also torn apart families.

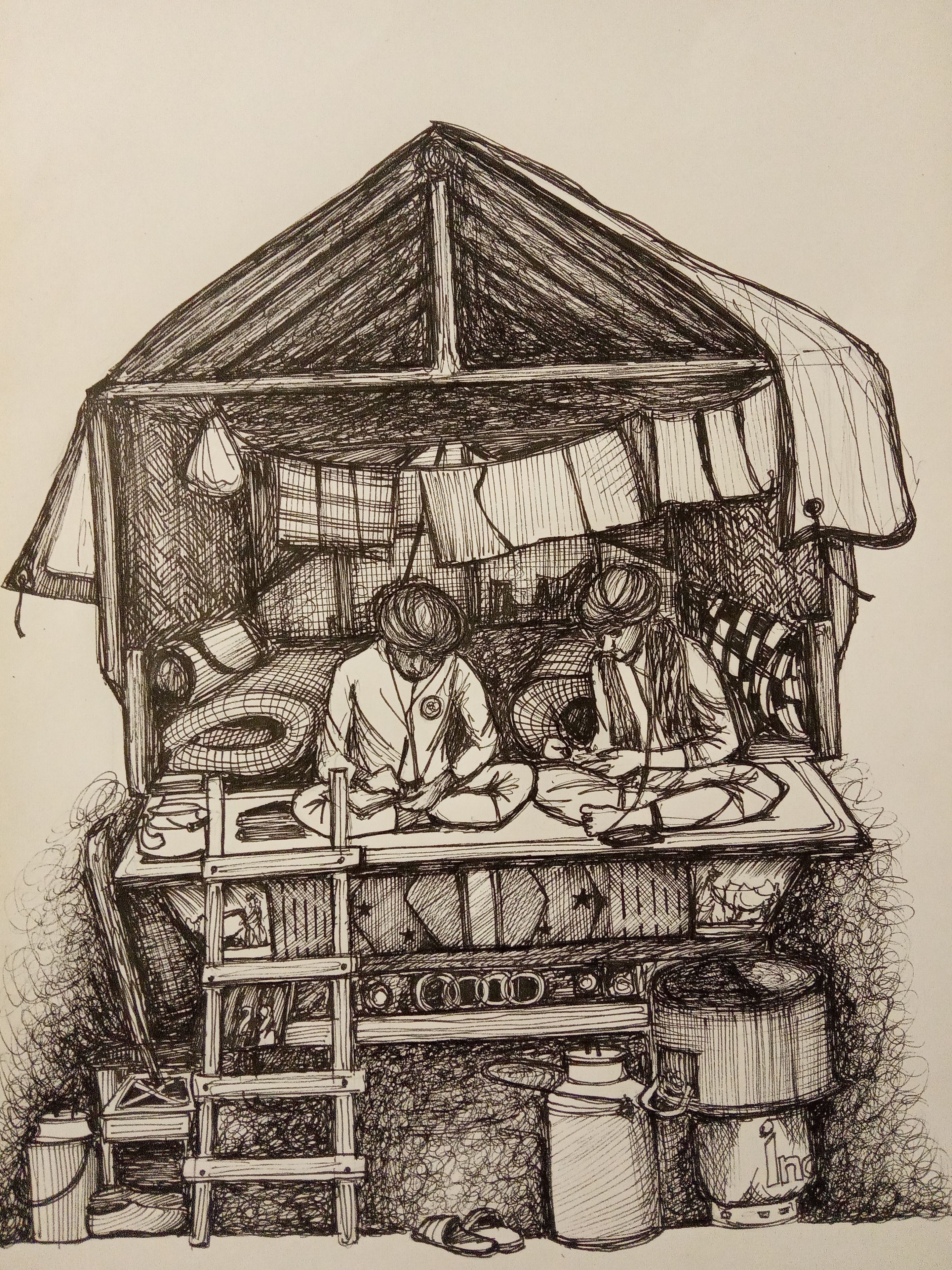

Photo by Sayed Muhammad Shah/UNAMA (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Second, many of the Afghan asylum seekers in Europe were born and grew up in Iran. They are the second generation of undocumented Afghans in Iran, lived their whole clandestine lives outside the official sphere of social life, rights, and norms. Afghanistan is for them a foreign country. Some of them have never been there before. When deported to Kabul they have nowhere to be integrated, no one to reunify with. Accordingly, in order to join their families, the majority of them have to cross borders irregularly to Iran, where they constantly face institutional discrimination. Third, the cost of the initial migration, often in forms of debt, is often not refunded. Deportation means also deletion of remittances, i.e. the source of livelihood for many poor families. Therefore, the whole household economy is affected by deportation. Generally, deportation negatively affects both the deportees and the receiving communities. Thus, the financial insecurity and unpaid debt force them to hide themselves or leave the country again.

Fourth, a common post-deportation experience is stigmatization due to the failure of the migratory project. Not unusually, deportees experience cultural estrangement, stigmatization, and high levels of violence. In the case of Afghan deportees, stigmatization has a cultural aspect as well, in terms of being ‘culturally contaminated’ by foreign cultures. Deportees are stigmatized and harassed for their accent, clothing, and behavior. Deportees who grew up in Iran face harassment and derision by being called iranigak (acting Iranian). For deportees from Europe, being associated with the West increases their vulnerability. Deportees are objects of suspicion and can be regarded as spies or kafir (unbeliever), since some asylum seekers convert to Christianity in Europe. Some have been exposed to suspicion and even violence just for having a foreign telephone number in the contact list of their cellphones. Moreover, being associated with the West make them easy prey for swindlers and robbers who believe they have forging currencies. Deportees in their country of citizenship are turned into denizens with limited access to their citizenship rights. Deportees’ rights can be suspended, rejected, delayed, and denied.

They are left vulnerable not only to the violence of the state, but also to the violence of ordinary citizens, without being able to protect or defend themselves.

Fifth, basically the main problem of deportees is disrecognition of their citizenship rights. In some cases, deportees even have difficulties obtaining ID cards. Since the majority of young Afghans who are deported from European countries to Afghanistan were born and grew up in Iran or Pakistan, it is not unusual for them to be denied Afghan national ID cards. Paradoxically, the same state that let them be deported to Afghanistan as Afghan nationals refuses to recognize them as citizens, since they “lack documentation” and are “not in the register system”. Sixth, another factor which makes life difficult and serves as a pull factor for remigration are the strong social ties remaining through relatives or friends in the deporting country. During time spent in Europe, many deportees had learned the language, made friends, maybe fallen in love, and become accustomed to the European lifestyle. The desire to reunify with friends and family members and the desire for a missed lifestyle push them to start a new migration again towards what deportation had deprived them of. The paradox in the logic behind deportation is that while on the one hand, returning emphasises family values and reunification in the country of citizenship (deportation is presented as “going back home”), on the other hand, it causes separation of families in the country one is deported from.

Seventh, young Afghan deportees, who have spent their formative years in the country they were deported from, have more difficulties in establishing networks and in finding their place in the society than middle-age deportees. Afghan asylum seekers are young. Afghanistan has been the country of origin for the largest number of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Not unusually, those who grew up in the host country do not even master the language assumed to be their “mother tongue.” Furthermore, a gap between their education prior to deportation and the education system in the country they are deported to prevent them from moving forward. Likewise, skills they have obtained are not always relevant and their certificates, if even available, are not always translatable or recognized, and therefore not useful after deportation.

Photo by Mariano Mantel (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Eighth, deportees are sent to a country which is already struggling with a high rate of unemployment, widespread poverty, social insecurity, and large internal displacement. According to report by the United Nations, the poverty rate is 36%; unemployment amongst young people (15-24 year olds) is 47%; 3.5 million of school age children are out of school; and there is widespread and chronical food insecurity. Furthermore, the security situation in Afghanistan has dramatically deteriorated in the past years. The number of civilian casualties has almost doubled since 2009. Added to all these problems, according to International Organization for Migration, over 700,000 Afghans returned or were deported from Iran and Pakistan during 2016.

Finding themselves in radical insecurity outweighs the risk of being caught and deported once again. A UNHCR report from 2012 shows that up to 80 per cent of the forcibly removed people to Kabul attempt to start a new migratory adventure within a short period of time after the arrival. Interestingly, there is a dialectical interplay between deportation and human smuggling; each Afghan deportee is a new client for human smugglers. Despite all efforts to deter and remove Afghan migrants, Afghanistan is still second leading country of origin of refugees. The young Afghans are stuck between a powerful transnational apparatus which forcibly exclude and expels them from the Global North, and on the other side the circumstances and the forces which push them towards emigration from the Global South.

Deportation as a disciplinary measure which would deter migration fails because the structural realities behind why people leave are ignored.

Therefore deportation, rather than stopping aspirant migrants, contributes to the upholding of the global inequality. So if deportation does not deter Afghan migrants, what justifies deportation policies? Young Afghan asylum seekers are usually second generation refugees. They are children of undocumented migrants in Iran or Pakistan, and many of them started their flight before reaching age ten. I have interviewed Afghans who have been crossing borders for more than a decade. Perhaps the Swedish word ‘flykting’ (someone who takes flight, who is on move) might convey more about the situation of young Afghans than the word refugee (someone who has taken refuge).

To sit down, to be settled, to be immobile and fixed in one place, performed metaphorically by the protestors in Stockholm, is what these young men and women need after years of walking, running, swimming, hiding, and fleeing.

Afghans are expelled from the Global North, but at the same time Afghanistan has been a playground for the Global North since 1979. Almost all rich countries have military presence there. We are there. Why should they not be here then? We should not deport them. Deportation to Afghanistan is politically irresponsible, ethically incorrect, and financially illogical.

Featured image by Jon Flobrant (www.unsplash.com)