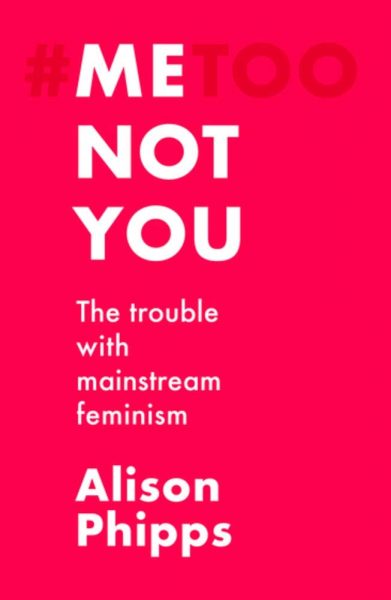

In Me, Not You, Alison Phipps uses the #MeToo Movement as a backdrop to her work to illustrate how privileged white women using mainstream feminism as a conduit, can silence, side-line and sacrifice both marginalised women and minorities. The kind of feminism promoted by media, institutions, corporations and the state, is what Phipps posits as “mostly Anglo-American public feminism” (pp.5). The work centres race as a springboard on a discussion of how white feminism, whether reactionary or mainstream, plays a role in violently reasserting whiteness. This scholarly work is essential, especially in a time when race is central to various movements across the world- from #BlackLivesMatter in the USA to #EndSARS movement in Nigeria. The reality is that across the globe there is a collective outcry for social justice which highlights the need for intersectionality within and across movements.

Intersectionality underscores the need to account for how factors such as class, gender and race inscribe meanings to the experiences of individuals.

Although scholars like Cho, Crenshaw and McCall (2013) and Hancock (2016) argue that intersectionality is critical to shifting approaches to politics, theory and methodology, others have dismissed it as “merely descriptive” (Alexander-Floyd 2012: 5). Moreover, some scholars have argued that intersectionality runs the risk of over-politicising the role of race within feminist discourses, which can potentially undermine the goal of feminism (Zack, 2005). Through gaslighting other scholars who raise the importance of race and the intersectionality of struggles, mainstream feminism privileges “white bourgeois wounds at the expense of others” (pp.80), making it easier to sacrifice marginalised people. Phipps argues that this is another way of saying “Me, Not You”. Intersectionality is central to feminist scholarship as it can help disrupt knowledge production and theorising that takes place in the “context of colonial and imperialistic conditionalities” (Wane,2008:193). Particularly, intersectionality underscores the need to account for how factors such as class, gender and race inscribe meanings to the experiences of individuals. There are myriad ways in which gender is experienced and white feminism turns to curtail this nuance. It is important to explore “alternative school of thoughts and counter hegemonic narratives” in feminist discourse and activist work (Tamale, 2020:43 ; Oloka-Onyango and Tamale 1995) because these varied “femininities of women do not easily fall into neat categories” (Mekgwe 2007: 21). As such, accounting for bodies that transcend gender binaries and norms is essential both within and outside academia walls. In her work, Phipps uses trans bodies to demonstrate the exclusionary politics of white feminism.

The book title is a play on the #MeToo movement, and Phipps suggests that the “Me” is about her as a white feminist and the “Not You”, a pointer to how white bourgeois mainstream feminism excludes. Because ‘the personal is political’, white identity’s narcissism is a narcissism under threat despite its position of domination and control. To counteract both mainstream or reactionary and trans-exclusive feminisms harness the ‘outrage economy’ (pp.36) to shape the political grammar and social markers of issues that require visibility. Because the “colonial/modern gender” system “accommodates rather than disrupt[s]” binary framings for understanding power (Lugones, 2008:23), mainstream feminism reinscribes this binary by policing bodies. Simply put, the #MeToo power dynamics reflect how carceral feminism and colonialism are inextricably linked. By other[ing] the bodies and communities of ‘natives’, the coloniser laid the necessary groundwork to justify violence instigated against these communities. An intersectional approach enables to visibilise race in activist discourses and knowledge production systems that play a role in [re]creating the ’other‘. Adding to this idea of creating the other, Lugones (2018:29) argues that “they [indigenous people] were understood as animals in the deep sense of without gender, sexually marked as female, but without the characteristics of femininity”. By categorising ‘natives who were deemed the ‘other’, the violence experienced by these bodies was deemed necessary to bring them closer to western values of civilisation (Said,1989; Sarukkai, 1997). For example, as trans bodies do not conform to gender essentialisms and dualisms (Chatterjee,1986), white feminism views and frames them as departing from western civilisation thus justifying the policing of such bodies.

Within the purview of politics of respectability, carceral feminism is dovetailed by a narrative of feminism that polices bodies that depart or deviate from what a woman is ‘supposed to be’.

Image by RODNAE Productions, courtesy of Pexels.com

Turning to the idea of respectability politics and justified violence, Kendall (2020, pp. 88) argues that “the structure of respectability requires adherence, not autonomy, and relies on dominant norms to create a hierarchy of privilege inside marginalised communities”. Within the purview of this politics of respectability, carceral feminism is dovetailed by a narrative of feminism that polices bodies that depart or deviate from what a woman is ‘supposed to be’. Because trans-bodies and the agency of individuals who participate in sex work threaten the “ideal woman” trope, white bourgeois mainstream feminism tends to police and “correct” these bodies. The very notion of carceral feminism hinges on punishing bodies that somewhat overstep the boundaries of what it means to be a woman within the confines of white bourgeois mainstream feminism, reflecting the link between carceral feminism and colonialism.

Throughout six chapters, Phipps addresses the book to her fellow white women/feminists and outlines how they can be active participants in fighting against sexual violence through their capacity to comprehend the intersectionality of struggles. Phipps effectively acknowledges her privilege as a white woman and perhaps, a scholar who is anxious about her whiteness while writing on issues of race (Ahmed, 2007). Many of the arguments she advances are nothing new for other scholars writing on how white women benefit from mainstream feminism and act as gatekeepers. However, her positionality allows her to put into dialogue different scholars and to thread together a consistent argument against mainstream feminism.

Being a victim and a perpetrator is not mutually exclusive as white women can still be victims of sexual violence yet be perpetrators of white supremacy through political whiteness.

The primary basis of mainstream feminism hinges on transnational solidarity over women’s issues, reflecting a universalistic approach that considers women’s issues as transcending nation-states and other markers of difference. By acknowledging her privilege, she advances one of the book’s fundamental premises: being a victim and a perpetrator is not mutually exclusive as white women can still be victims of sexual violence yet be perpetrators of white supremacy through political whiteness. Phipps deploys political whiteness to describe the relationship between mainstream feminism and white supremacist systems to highlight different types of behaviours and values that help concretise white supremacy. This includes “narcissism, alertness to threat and an accompanying will to power” (pp.6). She suggests that the interaction between supremacy and victimhood produces political whiteness which:

begins from the premise that white subjectivities are shaped by the structural position of white supremacy, and that whiteness and class privilege are fractured but not erased, by gender and other relations (pp.60).

By setting parameters of whose politics matter via the grammar fashioned from political whiteness, mainstream feminism can deploy narratives of “us” versus “them” when under threat, thus using victimisation when entitlement is lost. Some examples of this include white women breaking down/crying in situations when their privilege is called out or when they feel they do not have a platform to be heard. Therefore, the tears are both personal and political. The author suggests that political whiteness is underpinned by a form of feminism that does not seek to overthrow the system because white bourgeois women know the benefits, they can derive from it: they want a place, a voice, and visibility in existing power structures. Examples of this feminism include corporate feminism and governance feminism which is a form of “feminism [that] advocates for women on banknotes but does not necessarily dispute the hands that the majority of these banknotes are in” (pp.82). To gain solidarity and visibility in digital spaces, white bourgeois mainstream feminism uses trauma as a form of capital investment. This trauma relies on the currency of likes, shares and retweets. Through this, white bourgeois women can mask complacency in popular issues. Through their privilege and as gatekeepers of feminism, bourgeois white feminists hyper-politicise trans bodies to police gender expectations and notions of womanhood. On the one hand, they argue that these bodies threaten the safety of (white) women in various spaces which challenges institutions, structures and the state to protect or ensure their safety and comfort. One of these institutions include religion: the synergy that exists between mainstream feminists and the religious right conceals trans-exclusionary, conservative binary framings of gender and discriminates against trans and sex workers communities. On the other hand, white feminism positions trans bodies as a threat to gender expectations and its performativity (Butler,1999;1988). For capitalist patriarchy to function, the nuclear family must be protected so that the supply of able bodies is insured. In this regard, white feminism turns to religion to weaponize and police trans bodies because if patriarchy is unable to police who has sex with whom, where and how, it becomes difficult to keep women in the unpaid care economy.

Image by Kamaji Ogino, courtesy of Pexels.com

To police sex, anti-sex work groups frame sex work as paid rape and by doing so, these groups ignore and violate the agency of sex workers. Furthermore, equating sex work to paid rape diverts the attention away from core issues around sexual violence and the main perpetrators or structures that make it possible for rape to be used as a tool to wield power and control women. More importantly, women from marginalised communities who struggle for their livelihood because of the precarious conditions in which they live are sometimes exposed to sexual violence. Consequently, by turning to religion or to the idea that trans bodies threaten society’s social fabric, political whiteness reinforces the us versus them narrative.

The current war on so-called “gender ideology” has enabled mainstream feminism to emphasize women’s safety and turn to gender stereotypes to protect the nuclear family.

Firstly, the respectability politics surrounding sex within mainstream feminist discourses can be weaponised via the hyper-politicization of sex work as it can be framed as a catalyst to human trafficking, sexual immorality, and as a threat to society’s social fabric. Who has sex, where and how hinges on the idea and set up of the nuclear family. Sex work threatens the household narrative supported by white bourgeois mainstream feminism. Moreover, religion permeates into how the household is imagined (Reilly, 2011; Thornton, 1985), that is one man and woman coming together under the institution of marriage to procreate. It then becomes essential to ask: how do we situate gender in a far-right moving world? Addressing this question, Phipps suggests that mainstream feminism utilises performative trauma to advance a punitive agenda under the banner of protecting society in a context where the state is seen to be inactive. Under such a banner, “sex threatens the state” (Aderinto, 2014) because the issue of human trafficking emerges as state priority thus evoking strict citizenship regimes, the fortification of borders and hoarding of resources from communities who need them (Bernstein, 2012). These dynamics demonstrate that mainstream feminism is complacent in some of the violence it claims to be fighting. The current war on so-called “gender ideology” has enabled mainstream feminism to emphasize women’s safety and turn to gender stereotypes to protect the nuclear family. Perhaps more importantly, it becomes easier to gather public and state support since mainstream feminism can evoke rage by questioning how the state uses taxpayer money to supply resources to non-binary bodies and investment into educative programs regarding gender and sexuality. This is a reflection of how the intersections of neoliberalism and mainstream white bourgeois feminism have created “inequalities of distribution”, making it possible for the “good woman” (cis, respectable, implicitly white) (pp.107) to decide who has access to resources.

Collectively, the respectability politics dovetailed by white supremacy alongside white rage makes it possible for white feminism to have no issues with using the others as collateral damage

Secondly, Phipps highlights how white bourgeois mainstream feminism uses marginalised communities as collateral damage. The (mis) use of anger by white bourgeois feminism contributes to creating a society where “one side’s dehumanisation of the other is just presented as an opinion” (pp.96). Collectively, the respectability politics dovetailed by white supremacy alongside white rage makes it possible for white feminism to have no issues with using the others as collateral damage. White carceral feminism represents sex workers as underserving victims whose voices and experiences are erased (Andrijasevic and Mai, 2016; Bernstein, 2012). Through this narrative of underserving victims, white feminism makes it possible to increase punitive measures against sex workers which further marginalise them and intensify the precarious conditions they encounter in their profession. This demonstrates how white feminism also fails to consider the structures, histories and global processes that contribute to their precarity. Mainstream feminism is dovetailed by carceral and trans-exclusionary politics that instrumentalise marginalised communities when passing legislation (Gallagher, 2017; Gerassi, 2016). For example, the ‘migration crisis’ sparked conversations around how immigrants are responsible for increased unemployment, crime rates and public expenditures. This, in turn, created a “keep them out” reaction from different states (Weaks-Baxter, 2018:34; Berry Garcia-Blanco and Moore, 2016). However, the keep them out approach was deployed under the premisses of protecting individuals from being smuggled and dying at sea. Therefore, white bourgeois mainstream feminism can support such legislation by arguing that they protect marginalised women and children who may be victims of human trafficking and child labour (Sharma, 2017; 2003).

In short, reactionary trans-exclusionary and carceral feminism “amplifies the narcissistic Me, Not You of the mainstream” (pp.160). More importantly, this narcissism reveals the coloniality of gender (Lugones, 2016) and reinforces the position of white feminists as gatekeepers of what it means to be a ‘woman’ who can take up space, speak and be seen. The book raises important questions about the possibility of being an ally and comrade in struggles for equality. On the one hand, comradeship requires white feminists to play a role in disrupting systems surviving off political whiteness and to ensure that legislation and resources are available to those who need them. On the other hand, allyship means “supporting the struggle but not being in or of it” (pp.161). Is it possible to be there for support and let others take up space when white feminism is so much used to power and demands it? Following off the work of Sara Ahmed’s (2017) ‘killjoy survival kit’, the conclusion outlines six key questions white feminists can ask themselves in their everyday activism and advocacy work. Phipps suggests that the solution is not to dump the ideologies of white feminism but to examine how their existence has enabled certain narratives. Thinking from this perspective can help “dismantle power, not merely demand a shift in who wields it” (pp.164) as a critical examination can produce “solidarities of care” which can benefit us all (Emejulu and Bassel, 2018).

References

Aderinto, S., 2014. When Sex Threatened the State: Illicit Sexuality, Nationalism, and Politics in Colonial Nigeria, 1900-1958. Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

Ahmed, S., 2007. A phenomenology of whiteness. Feminist Theory, 8(2), pp.149-168.

Ahmed, S., 2017. Living A Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

Alexander-Floyd, N., 2012. Disappearing Acts: Reclaiming Intersectionality in the Social Sciences in a Post-Black Feminist Era. Feminist Formations, 24(1), pp.1-25.

Andrijasevic, R. and Mai, N., 2016. Editorial: Trafficking (in) Representations: Understanding the recurring appeal of victimhood and slavery in neoliberal times. Anti-Trafficking Review, (7).

Berry, M., Garcia-Blanco, I. and Moore, K., 2015. Press Coverage Of The Refugee And Migrant Crisis In The EU: A Content Analysis Of Five European Countries. [online] Cardiff. Available at: <https://www.unhcr.org/56bb369c9.pdf> [Accessed 02 Feb 2021]

Butler, J. (1988). Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), p.519.

Butler, J. (1999). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Bernstein, E., 2012. Carceral politics as gender justice? The “traffic in women” and neoliberal circuits of crime, sex, and rights. Theory and Society, 41(3), pp.233-259.

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. and McCall, L., 2013. Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), pp.785-810.

Emejulu, A. and Bassel, L., 2018. Austerity and the Politics of Becoming. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56, pp.109-119.

Gallagher, A., 2017. What’s Wrong with the Global Slavery Index?. Anti-Trafficking Review, (8).

Gerassi, L., 2016. A Heated Debate: Theoretical Perspectives of Sexual Exploitation and Sex Work. NCBI, 42(4).

Hancock, A., 2016. Solidarity Politics For Millennials. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Lugones, M., 2016. The Coloniality of Gender. In: W. Harcourt, ed., The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Development. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mekgwe, Pinkie. “Theorizing African feminism (s). The ‘colonial’ question.” Matatu 35, no. 1 (2007): 165-174.

Oloka-Onyango, Joseph, and Sylvia Tamale. “The personal is political, or why women’s rights are indeed human rights: An African perspective on international feminism.” Human Rights Quarterly. 17 (1995): 691.

Amadiume, Ifi. Male daughters, female husbands: Gender and sex in an African society. Zed Books Ltd., 2015.

Oyěwùmí, Oyèrónkẹ́. The invention of women: Making an African sense of western gender discourses. University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Reilly, N., 2011. rethinking the interplay of feminism and secularism in a neo-secular age. Feminist Review, 97(1), pp.5-31.

Said, E., 1989. Representing the Colonized: Anthropology’s Interlocutors. Critical Inquiry, 15(2), pp.205-225.

Sarukkai, S., 1997. The ‘Other’ in Anthropology and Philosophy. Economic and Political Weekly, 32(24), pp.1406-1409.

Sharma, N. (2017). ‘The New Order of Things’: Immobility as protection in the regime of immigration controls. Anti-Trafficking Review, (9)

Sharma, N., 2003. Travel Agency: A Critique of Anti-Trafficking Campaigns Nandita. Canada Journal of Refugees, 21(3), pp.53-65.

Spivak, G., 2010. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” revised edition, from the “History” chapter of Critique of Postcolonial Reason. In: R. Morrison, ed., Can the Subaltern Speak?: Reflections on the History of an Idea. New York: Columbia University Press, pp.21-78.

Tamale, Sylvia. 2020. Decolonization and Afro-feminism. Daraja Press: Ottawa

Thornton, A., 1985. Reciprocal Influences of Family and Religion in a Changing World. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47(2), p.381.

Wane, Njoki .2008. “Mapping the field of indigenous knowledges in anti‐colonial discourse: A transformative journey in education.” Race Ethnicity and Education 11, no. 2: 183-197.

Weaks-Baxter, M., 2018. Leaving The South: Border Crossing Narratives And The Remaking Of Southern Identity. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Zack, N., 2005. Inclusive Feminism: A Third Wave Theory of Women’s Commonality, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Featured image by Jiroe, courtesy of Unsplash.com