Allegra’s thematic thread on #postsocialism is coming to its end. We hope that the eight delicious specialties Allegra served you over the past two weeks have pleased your taste buds, dear Allies, in a nuanced and gentle way.

We joined one artist and four anthropologists who mastered both careful observation and bold participation in their exploration of borders and border-crossing points as events, performances and improvisations. We pondered over the art of being IN and the impossibility of a “view from nowhere”. We broke (or at least, imagined breaking) walls between art and science, between imagery and documentation, between observer and the observed. Today, our final thoughts regard those walls that are still standing – memories.

Memories are complex phenomena. Memories as living past represent the way in which past occupies its space in present; memories are present-time containers for gone, already lived-through moments. Memories as living with the past validate previous experience and introduce them to the ongoing process of determining and interpreting the present reality. Finally, memories as living in the past create the substance of nostalgia, a phenomenon that often goes hand in hand with idealization of the past experiences and events.

We started the thematic thread with a virtual personal exhibition #SommerWende. Photographs by Axel Schön that we have on display in #AVMoFA become a kind of visual memoir (living past), a personal observation about people and events that may or may not mirror the collective memory consolidated around the early transition years in the ex-Soviet Union. The stories behind the photographs – as remembered and reproduced by the artist in an exclusive #interview – add a dimension of living with the past to the ‘neutral’, documentary character of the imagery.

Reportage photography, an attempt to capture the situation that is unfolding now, with years passing by, becomes a memoir, a document of the time that can foster complex memory phenomena.

Taken out of the socio-political context these works function at a personal level, as intimate life stories. Once understood within the surrounding reality and connected to the transformative events that are recognized as the milestones of a certain historical period, they become vulnerable to a speculative generalization exercise. Bare photographs, probably even more than other art forms, are both incredibly strong in their depictive vividness and dramatically weak in their interpretative openness. Put into the virtual space of #AVMoFA, these photos become a part of Allegra’s museum heterotopia, a place existing neither here nor there to capture simultaneously objects living in the past and placing them beyond time and space.

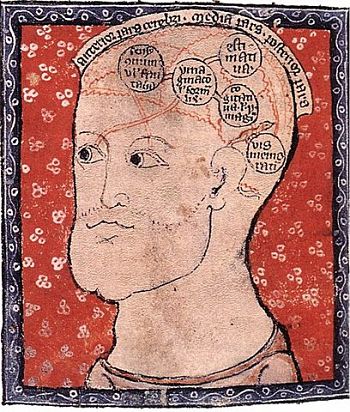

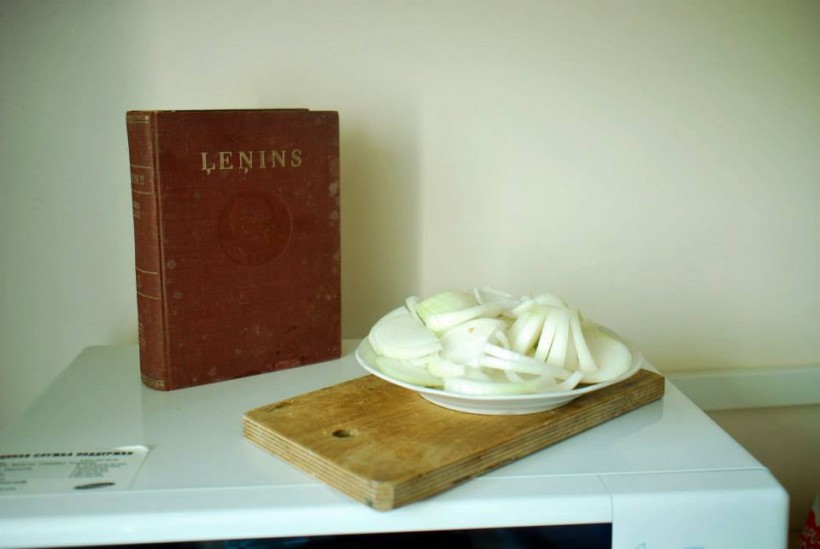

Almost all around the world, photos have become the most common, direct and habitual form of enslaving memories in gigabytes conveniently offered by modern digital devices. Yet, memory holding properties are inherent to symbols such as bears in Russian political rhetoric, territories that became simulacra, border-crossings, foods and eating. These memories are mirrors that generally reflect ‘the big picture’, but tend to reinforce and distort the nuances, all at once or one at a time.

Memories outline the borders between remembered and forgotten. Their inherently synthetic nature is prone to a blend of experience, affect and desire.

The essays and reviews in our curated weeks explored postsocialism today not only as a shared, collective memory of the socialist past, but also as a very vivid and imposing experience that shapes the present of millions of people in the former Soviet Union. The phenomenon of Soviet nostalgia showed through political rhetoric on Crimea returning ‘home’ to Russia, as well as through collective food memories as explored by the Searching for (post-)Soviet taste. At the same time, this political reality can well be placed in the context of the recent proposition about the 30 years memory stagnation in Russia put forward by Alexander Etkind from Cambridge. In the light of the ongoing Ukrainian crises and distancing of Russia from the rest of Europe – and even from most of the rest of postsocialist space – revisiting and putting into the spotlight the workings of memory in contemporary postsocialist societies is pivotal.

Moving on from postsocialism to a new socio-political and cultural reality means dealing with the memories of ‘the way it was not.’ Though living with the past may be a task that requires both conscious effort and collective will, a sober consideration of the living past through routinized reflexive observation of artifacts as memories and recapturing the borders these memories imply can be considered as the first step in the process of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or coming to terms with past.