On Sunday 7 July 2015, the Cameroon Radio and Television in its weekly Sunday Program, Cameroon Calling, broadcasted what shocked the public audience. It had chosen as its theme “The return of trafficked Cameroonian girls from Kuwait”. In the follow up to the program, young girls who had gone in search of ‘greener pastures’ through a very complex network orchestrated by middlemen in Kuwait and other Gulf States narrated their ordeals while in those countries. They had returned to Cameroon through the providence of the embassies of other African countries and NGOs, in particular the Central African Republic in Kuwait. They had apparently been lured to these Gulf States by mediators using very juicy stories to convince them of the availability of jobs and high pay packages. Comparing that to the poor financial situation in their country, these young people fell prey to the drag net of the recruiters.

It is relevant to profile some of the voices of the returnees so as to better understand not only the youth mobility but also their bondage and ultimate freedoms in national and transnational perspectives. One of the girls recounted how she was forced to share a room with four cats while another recounted how she was forced to have sex with her master on several occasions. When she brought the matter to the attention of the wife, both the husband and wife planned to kill her. Another one recounted how her educational certificates were confiscated along with her passport and her entire belongings. After a long struggle, she finally arrived home with a single dress on her. Others narrated how they were always subjected to eating stale food, going to sleep late and waking up early, thereby working at most 20 hours a day (1).

These narratives suggest the bondage in which humanity has often found itself in unknowingly. Although narrated yesterday, this typology of youth trafficking has a historical depth stretching to the period of slave trade.

Youths as the cream of every society have always been the torch bearers of geographical mobility. During the slave era, the African youth population were those who were sold into the obnoxious trade. Yet the demise of slavery and slave trade, which was largely sustained by slave merchants in the 19th and 20th centuries, gave rise to new forms of slavery and slave merchants in Africa. Colonial Africa witnessed the emergence of a new elite who were responsible for the mobility of laborers, housemaids, babysitters, garden boys, and cooks just to name but a few to serve in plantations or in the homes of senior officials. Despite its abolition, Cameroon now experiences newer forms of slavery.

The historical depth: Trans-Atlantic Slave trade

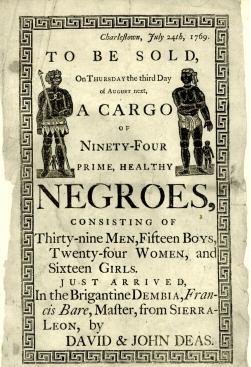

Youth mobility and bondage on a broader scale began with the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which has occupied volumes (Inikori, 1992; Austen and Derrick, 1999; Northrup, 1994; Klein, 1993, Iliffe, 1995). Generally it was the procurement of slave from Africa to the Americas. Africans never became slaves until they were kidnapped and arrived in America. Before then an African was a free man/woman first before he was captured. Despite the replete literature, it is still to be examined as the beginnings youth bondage in West Africa. Within a period of three hundred years, more than sixty million Africans were evicted from their villages and shipped across the Atlantic to work in the plantations. European powers which included Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, carried out the trade.

Undoubtedly, and with some few exceptions, European buyers purchased African captives on the coasts of Africa and the transaction between themselves and Africans was nothing more than a form of trade.

One could reasonably see that it was also true that very often captives were sold and resold as they made their way from the interior to the port of embarkation (Rodney, 1974). And within this period the youths were all in chains. The process by which slaves were obtained in Africa in general and West Africa in particular was not trade at all. It was through warfare, trickery, banditry and kidnapping (Rodney, 1974). When one tries to measure the ramifications of the Trans Atlantic slave trade on the African continent, it is essential and relevant to realize that one is measuring the net effect of social terrorism and/or social violence rather than just trade in any normal sense of the word.

The beginnings of industrial revolution led to the decline and eventual demise of the Atlantic Slave trade. Although scholars have argued differently that it was the result of the trade being evil, the general consensus that explains the end of the trade is that the Industrial revolution, which began in England, witnessed the relevance of machines in doing the same work that the slaves were doing, and faster too. Slave labour thus became redundant. The same European powers who had been at the heart of the slave trade introduced the legitimate trade in which Africa again became a victim and through that legitimate trade European powers came to colonize Africa.

Slavery memorial monument in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Photo by David Berkowitz, CC BY 2.0

Youth and Mobility at national level: Bondage and Freedom

Several dynamics were responsible for the geographical mobility of the youths. Both at the national and transnational level, youth mobility has to an extent been a subject of bondage and freedom. The demise of slavery and the slave trade, which was largely sustained by slave merchants in the 19th and 20th centuries, gave rise to new forms of slavery and slave merchants in Africa. Colonial Africa witnessed the emergence of a new elite who were responsible for the mobility of laborers, housemaids, babysitters, garden boys, and cooks to name but a few to serve in plantations or in the homes of senior officials. Labour and migration have become quite topical in contemporary Africa (Amin, 1974; Harris, 1994; Onselen, 1980). The colonial enterprise, with all its trappings, led to the migration and employment of youths.

Although Europeans initially saw Africans as untamed savages, hewers of wood and drawers of water, it soon became evident that for the smooth functioning of the colonial home, African youths were required.

Based on Victorian ideologies, colonialists gave priority to the employment of boys as gardeners, drivers, cooks and washermen. Much scholarship on domesticity has been on women. As Bujra’s (2000) study of domestic service in Tanzania shows, there is clearly much to be learnt about male servants in the domestic spaces. This line of reasoning is adopted in this essay.

For the colonial state to regulate and control this social category, it passed the Master and Servant Ordinance. The Master-Servant Ordinance was applied to the Cameroons and Nigeria and was passed on 27 February 1924. Ordinance 3 provided regulations on domestic labour and the number of hours of work for their masters.3 Further to the Master/Servant Ordinance was contract labour, which the Germans introduced in the plantations. The introduction of contract labour involved the continuous use of hired labour in a camp for a period that ranged from a few months to five years. The workers were paid half of their wages with the remaining half given to them when the contract expired and the workers were returning home. The Germans justified that it was the workers’ own good, a justification that needs further investigation.

Christianity needed cooks, houseboys, mission boys and gardeners just to name a few. These people were required to put on new costumes which distinguished them from their peers. Some of these houseboys, once they put on their new costumes, felt and thought that they were dehumanised and humiliated in the eyes of their wives. This was because the ordinary thinking and doing of household chores were done by women, not men. Cooking, doing laundry and taking care of the children were the responsibility of a woman, so if a man was doing these things there was something wrong.

Christopher Fuka, a mission boy, said that “My first trouser which was khaki was given to me by Rev. Fr. Thomas Burke Kennedy with an apron which had a string to tie across my waist. When I put it on I felt as though I was a woman (He laughs). It was ridiculous”.5 This type of dressing and the daily horarium of these domestic servants cannot be divorced from bondage.

Picture from Wikimedia Commons

The parallel of mission boys was convent girls who were also subjected to similar treatment. They were ‘quarantined’ in the nunnery and performed all sorts of duties ranging from gardening, cooking, laundry, ironing, taking care of orphans in the orphanage, and feeding pigs and chickens. The time of work was limitless and possibly ranged from 5:30 am when they woke up till 10 pm when they went to bed. Those who played the roles of baby sitters in the orphanage hardly slept smoothly, as they were intermittently disturbed by the cries of the orphan children. Apart from convent girls who combined multiple functions, there was a need for babysitters or nursemaids in the homes of the few powerful elites.

Babysitters combined many functions ranging from taking care of the child during the day as well as late in the night; cooking food not only for the child but also for the whole family, sweeping and mopping the floor, among other things. This could last for a year or two depending on verbal agreement. After that she was given a small token to help her undertake any artisan trade. Some were dismissed on trivial counts as low as being caught stealing some few cubes of sugar or drinking the child’s milk.

Traders were also masters of caging the youths. A case in point in Cameroon was the Bamenda Grassfields. Trade in the Bamenda Grassfields contributed to the geographical mobility of people and the rise of youths. This trade was on a regional and long distance basis. Traders were in need of carriers as well as other workers to take care of their daily needs. Youths therefore were of paramount importance to them. For traders, the possession of youths meant additional wealth and prestige. The more youths a trader kept under his control the more power he wielded.

One sub-social group that emerged as a result of trade was called ‘boy boy,’ which actually meant house boy. Broadly speaking, these were young men who served a renowned trader for several years, accumulated enough capital and then began their own business. In certain quarters some of these youths became part of the ‘family’ of the trader. An example was Godfrey Chongwain who was born in c.1919 and at 21, that is, in 1940, he served Stephen Mukalla who was a trader. Godfrey accompanied Stephen on his trading trips to Yola, Port Harcourt, Onitsha and Victoria. In addition, he ran errands for Stephen, harvested coffee on his farms, did laundry and accompanied Stephen’s children to school. He lived in Mukalla’s compound until he got married to Thecla FukuinYuh in 1946. She gave birth to their first son, Christopher Chongwain in 1950, in Mukalla’s compound.

Kumbo, Cameroon. Photo by Tavmjong via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Godfrey eventually started his own business. While a domestic servant, he was always up at the third cock crow, that is, 3:30 am, and only went back to bed after the domestic chores. In an interview, Chongwain said “It was a very difficult job but I persevered. I could never foretell what would happen the next day, nor where I would be sent to. I was always expected to be back in record time, which meant that no matter the distance, I did it running so as to make good time. I hardly had any payment in terms of money for myself”.7 Chongwain’s story was a tale of what youths went through. It is also relevant to note here that the rise of traders was a key factor in the changing definitions and roles of youths. Here they became carriers and sometimes became part of the family, though not treated fully as kin.

Recruitment of youths and their mobility

There were several ways of recruiting domestic workers. Amongst them were three main methods by which domestic workers had contact with employers. This was through their relatives, parents, and friends. The need to assist family members in urban areas who were probably wealthy and could foster a kin’s child’s social mobility was partly responsible for the increased participation of females/males in domestic work. Domestic workers also made contacts with employers through recruitment agents. Such agents were however scarce in developing countries as compared to developed economies. In this case, negotiation was between employers and these agents.

Youth recruiters were not a particular corps of people set apart for this duty. Indeed, recruiters ranged from parents, uncles, family friends and plantation workers. The history of recruitment and recruiters in colonial and post-colonial Africa is well established. In broad terms the recruitment of workers involved relatively large numbers of men and women who facilitated their transportation to their place of work within a short period of time. It also involved close supervision of the recruits and the provision of accommodation and food (Muyoba, 1983). Although in broad terms this is what goes into labour recruitment, little scholarship has been devoted to domestic labour in Cameroon. Richardson (1977) has noted that the Transvaal Gold mining established a recruiting and shipping company in 1904 known as the Chamber of Mines Labour Importation Agency, whose sole function was to recruit Chinese labour.

The case in Cameroon was different. Certainly, this is because youths were not recruited en masse. They were recruited individually and this was done based on trust.

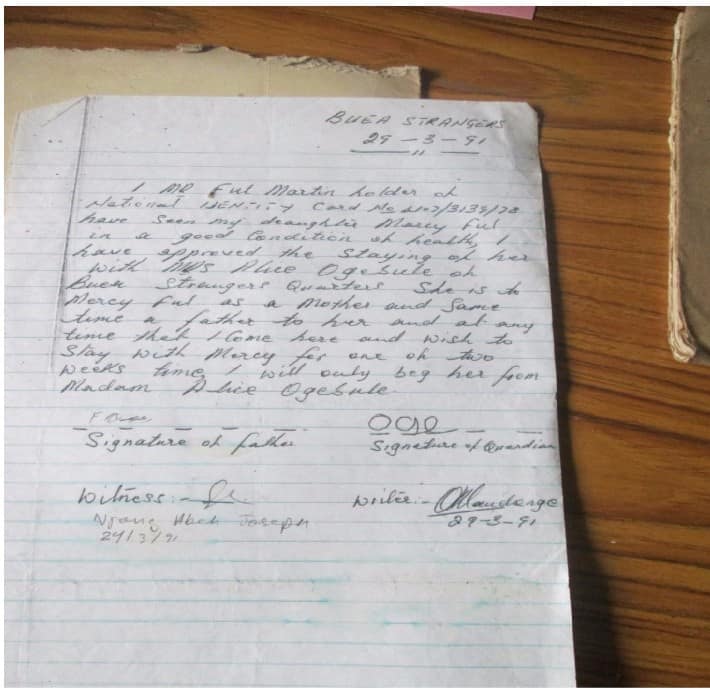

There was trust between the recruiter and the domestic servant; between the employer and recruiter; and between the parent of the domestic servant and employer. Once the trust was cemented, the domestic servant started work pending the establishment of a contract. The contract was verbal or written, and in certain circumstances the father was the one who gave out his daughter to the employer. A sample of a written contract is presented below, and although it falls out of the time bracket of this article, it could illustrate what a typical contract looked like. Written on 29 March 1991, Ful Martin signed a kind of contract in Buea, some 400 kilometres from Bamenda where he came from. In the contract he stated that he had seen his daughter living well with Alice Agebule. The so called ‘contract’ suggested that her daughter Mercy Ful was to work and live with Alice. It is not stated in the contract how long she would work per day nor the type of job she was engaged in. Such ‘contracts’ were rampant and this one is just the tip of an iceberg. Interestingly enough, it appears there were no contracts found during the colonial era.

Source: File Si (1991)2, Youths in Southwest Cameroon (NAB)

This contract indicates a marked change in the labour regime of youths. First, the creation of urban cities during the colonial and post-colonial period led to the rural migration of many people in search of jobs. Those who got the jobs were most of the time so busy carrying out their work that both husband and wife could simultaneously be out of the house. The need for youths to help out in domestic chores became necessary. The continuous migration of people from the rural to urban centres led to changes in thinking and action. Parents literally gave out their children to either improve their conditions or allow the children to improve themselves. It did not matter much to the parents the difficulties and challenges which their children experienced. However, the challenging situation of youths in Cameroon did not go on sine die. Consequently, they formed an association to address their grievances.

Youths in Transnational Spaces

The mobility of youths from national to transnational spaces can be explained in several dynamics but fundamentally unemployment appears to have been at the crux of their mobility. Youth unemployment the world over is blighting a whole generation of youngsters. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that there are 75 million 15-24 year olds looking for work across the globe. An estimated 26 million youths are not in Education, Employment or Training (so-called NEETs). Globally, about 85% of the world’s young people live in developing countries and an increasing number of these young people are growing up in cities. In many cities on the African continent, more than 70% of the inhabitants are under the age of 30 with about 65% of the total population below the age of 35 years, making Africa the most youthful continent in the world.

Photo by Philippe Semanaz, CC BY-SA 2.0

In Cameroon the unemployment rate is 30% while that of underemployment stands at 70% (International Labor Organization’s 2013 report). But any casual observation in Cameroon suggests that the ILO report was a bit faulty. It is worth noting that Cameroon has a population of over 20 million inhabitants and most of the people belong to the youthful age. It is relevant to know that the working population of Cameroon is about 12 million and only a little over 200,000 people work in the public service. With government being the highest employer, this implies that the other 11.8 million people who are not government employed are a call for concern.

It is true that the Cameroonian government has become aware of the dangers posed by the growing rate of youth unemployment and has made moves in that regards. This can be seen through the Ministries of Youth Affairs and Civic Education and that of Employment and Vocational Training. The programs designed by government via these ministries include the Rural and Urban Youth Support Program known by its French acronym as PAJER-U, the Integrated Project for Manufacturing of Sporting Materials (PIFMAS), the National Employment Fund (NEF) and the Integrated Support Project for Actors of the Informal Sector (PIAASI). All these programs have their success and failure stories. But the bottom line is that, despite all these efforts made by government, a lot more still has to be done.

“Strengthening Micro-Entrepreneurship for Youth” could be the solution. Simply put, a comprehensive entrepreneurship program that combines skills and business development training, mentoring and financial support will significantly improve the chances of starting a successful business and fostering existing ones, thereby creating employment opportunities and hence reduce unemployment. Some African countries have recorded success stories in this venture. Cameroon will certainly not be an exception.

It is no doubt that youth unemployment is one of the major challenges Cameroon faces today as thousands of young people find no opportunities after school. The effect of this “cankerworm” is ravaging and dragging the country’s economy down. This will go a long way to delay its most talked about emergence come 2035. Some of these youths engage in the search for “greener pastures” abroad – thus migration and brain drain.

For those other youths who are not daring enough, the end results are usually high crime waves, street children, teenage pregnancies, sexual harassment, drug abuse, and gambling, amongst other ills.

Many young people remain marginalised from social and economic opportunities, with limited access to essential resources, particularly education. Youth are among the most vulnerable of all persons the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) aim to reach. Inter alia, the setbacks of lack of education, maternal mortality, HIV/AIDS, unemployment, environmental degradation on young people, especially girls, are far reaching. This is because many young people often lack access to adequate information, schooling, basic social amenities and basic rights, and these are often overlooked in national development agendas. Therefore, the inclusion of young people initiatives geared toward any national or international development is crucial to ensure a successful and sustainable outcome for all.

The situation of the youths did not remain static in Cameroon. In April 2003, the Cameroonian government adopted the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP), which was a holistic document aimed at reducing the poverty level in Cameroon. Six years on, in November 2009, the Minister of Economy, Planning and Regional Development presented the Growth and Employment Strategy Paper (GESP). The GESP builds on the shortcomings of the PRSP. Quoting the Minister, the GESP did not help to bring the youths out of their social and economic doldrums.

Construction of Burj Dubai, Jan 2008. Photo: Imre Solt via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

The improvement in communication technology such as the internet has also forced the youths to find various ways of moving out of the country. Through the internet they come to know of existing opportunities elsewhere in the world, which gives them the anxiety to exploit them. Also through the internet smarter youths have been able to create very complex networks with organization and people in far off countries like the Gulf States. Through such networks, they could easily woo their desperate peers by exploiting them economically and sending them into bondage. Repeated stories are heard of “Get a Visa and work in Kuwait, Dubai, USA, Canada in two weeks”, “Study and work in so and so country”. Attached to these stories are mobile numbers for clients to call. Through these channels thousands of Cameroonian youths have moved out to various destinations. Their stories at the areas of destination have remained the same. They are forced to work 18 hours a day for very little pay. Some are raped while others are forced to sleep in the same room as their masters’ and mistresses domestic animals.

Transnational spaces appeared to have provided greener pastures to the migrants. Deeper, the methods which they were recruited showed that they were going into voluntary bondage. These young girls were recruited through a very complex network. Juanna was one of these victims and narrated her ordeal in the following words:

“Somebody approached me and hinted me that there was work in Dubai. I told the man that I was not having money even to feed myself led alone going to Dubai and my parents had died long time ago. He said that he will do everything from getting a visa to flight ticket and the job over there. After three months he told me that my passport was out and visa and that I will be flying to Dubai the next week. I asked whom I was going to meet at the airport. He simply told me that I was going to meet the person who will give me the job. It was only at the Douala Airport that I had my passport and visa and then board the plane to Dubai When I arrived the airport, somebody was standing there with a placard carrying my name. She took me to the house and immediately gave me instructions. There was no time allowed for me to rest neither to change my dress. I was told in frank terms that they spent 1.5 million francs to bring me to Dubai and I have to work and pay all the money. There was no chance to call back my relatives. My phone was seized and I ate very little having time to rest.”

The youths’ search for freedom and greener pastures is ambiguous. Almost all of them got their freedom through providence, such as through the existence of charitable NGOs, or they flee to foreign embassies where they are repatriated back to Cameroon.

This is unlike the colonial period when the youths gained their freedom through the formation of associations. Many are still held in bondage and cannot be returned to their areas of origin, yet neither are they comfortable in the diasporic spaces. For those who have gained their freedom, they are constantly going through the traumas of being held in “captivity”.

Notes

References

Amin, Samir (1974), Modern Migrations in Western Africa. London: Oxford University Press.

Ardener, Edwin; Shirley, Ardener; and Warmington (1960), with a contribution by M. J Ruel, Plantation and Village in the Cameroons: Some Economic and Social Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Austen, R.A. & Derrick, J.1999. Middlemen of the Cameroons Rivers: The Douala and their Hinterlands, c.1600-c.1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Austen, R.A. & Derrick, J.1999. Middlemen of the Cameroons Rivers: The Douala and their Hinterlands, c.1600-c.1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Booth, B. F. (1973), Mill Hill Fathers in West Cameroon: Education health and development, 1884-1970. Bethesda: International Scholars Publication.

Chilver, E.M., (1966), Zintgraff’s Exploration in Bamenda, Adamawa and the Benue Lands, 1889-1892. Buea, Cameroon: Ministry of Primary Education and social welfare and West Cameroon Antiquities Commission.

Eltis, D. 1983. “Free and coerced transatlantic migrations: some comparisons” American Historical Review, Vol. 88(2): 251-280 . .

Eltis, D. 1987. Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. New York: Oxford.

Eltis, D. and James Walvin 1981. The Abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press..

Eltis, D. and Lawrence C. Jennings 1989. “Trade between western Africa and the Atlantic world in the pre-colonial era” American Historical Review, Vol. 93(4): 936-59.

Harris, P. (1994), Work, Culture and identity: migrant laborers in Mozambique and south Africa, c.1860-1910: social history of Africa. London: James Currey.

IIiffe, J. 1995. Africans: The History of a Continent. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inikori, J.E. (1992) “Africa in World History: the export slave trade from Africa and the emergence of the Atlantic economic order” In B.A. Ogot (ed) General History of Africa, Vol. V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Heinemann/California/UNESCO: University of California Press.

Klein, M.A. (ed) 1993. Breaking the Chains: Slavery, Bondage and Emancipation in Modern Africa and Asia. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Konings, P. (1993), Labour Resistance in Cameroon: Managerial Strategies and Labour Resistance in the Agro-industrial Plantations of the Cameroon Development Corporation London: James Currey and Heinemann.

Manning, P. (1990), Slavery and African Life: Occidental, Oriental and African Slave Trades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Muyoba, G. (1983). Labor Recruitment and Urbam Migration: The Zambian Experience. PhD Thesis, University of Washington.

Ndi, A. M. 2005, Mill Hill Missionaries in Southern West Cameroon 1922-1972: Prime Partners in Nation Building Nairobi: Paul’s Publications Africa

Neba,,Aaron S. (1982) Modern Geography of the United Republic of Cameroon (New York: Hamilton.

Nkwi, W.G. (2014). “Domestic Servants in the Labour History of Colonial Cameroon from Early 1930s to Early 1960s”, Ghana Social Science Journal, Vol. 11(1): 77-103.

Nkwi, W.G. (2011). Kfaang with its Technologies: Towards a Social History of Mobility in Kom, Cameroon, 1928-1998. Leiden: ACS Publication.

Onselen, Van, C. (1980), Chibaro: African Mine Labour in Southern Rhodesia, 1900-1933 Johannesburg, South Africa: Ravan Press.

Rodney, W.(1981). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Howard: Howard University Press

Rudin, Harry (1938), Germans in Cameroon, 1884-1914: A Study in Modern Imperialism. Yale: Yale University Press.