In some research contexts, it is all but impossible to neglect the visual. Prior to beginning research on knowledge and intimacy in Seychelles and in London (with the Seychellois diaspora there), I knew that visuality would be an important focus of my fieldwork. This awareness came not only from surveying the literature, but from my own kinship ties to Seychelles, through the maternal side of my family.

While I was prepared to investigate the visual aspects of everyday life in Seychelles and London, it had not occurred to me that I might wish to express any of my findings visually.

But my interactions with artists and artisans led me to rediscover quintessentially Seychellois techniques that I had been taught, and to think about how I might make use of them.

Seychelles is made up of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean, 4 degrees south of the equator. Originally uninhabited, the islands were settled by the French during the period of European colonial expansion in the 18th century. In the 19th century they were ceded to the British. Seychellois claim descent from Europe, Africa, and Asia, though most of the population is Afro-Creole – a consequence of the importation of African labour into the islands, initially through slavery, to work on coconut and cinnamon plantations. In the 1970s, growing anticolonial sentiment among Seychellois led to independence from Britain, followed by a coup led by the socialist political party. The islands became a tourist destination during this period, and tourism remains a major economic pillar.

These historical processes engendered a particular kind of visuality among Seychellois.

Social and racial hierarchies meant that it was important to be able to place individuals visually: in terms of race and ethnicity, as well as family, wealth and social standing.

The visual was a means to gauge respectability – a term coined by anthropologist Peter Wilson (1969) in relation to Caribbean post-plantation social structures, but equally relevant in Seychelles. He described respectability as the rationale for colonial domination, rooted in the idea that white Europeans were inherently morally superior to colonised peoples, for whom they would serve as an example. Those who were furthest from being respectable, by dint of skin colour, occupation, or lack of resources, could still participate in respectability by conforming as closely as possible to ideas associated with whiteness and cosmopolitanism (Wilson, 1973). In post-plantation societies, the appearance of things is therefore closely linked to morality (Miller, 2010).

An important element of colonial-era respectability in Seychelles, as in the Caribbean, was being part of a respectable family.

The ideal was a patriarchal European family, in contrast to the female-headed households that were common and remain so in the present day. This could be signified via clothing and the presentation of one’s house (lakaz in Seychellois Kreol), especially the intermediate (semi-private and semi-public) space of the sitting room. A mid-20th century ethnography of Seychelles describes the care and attention that mothers took in dressing their children smartly, and the attention paid to their own clothes; it also details the ways that both women and men contributed to the home as a space, through decorating it (Benedict & Benedict, 1982). For the white planter families, ensconced in the gran kaz (big house) on the plantation, this meant sturdy wooden furniture and finely-worked embroidery, lace doilies, and paper silhouettes. These elements were mimicked at every level of society, finding their most rudimentary expression in the corrugated iron houses of poor Seychellois. The walls of these houses were decorated with collaged magazine cut-outs.

A recreation of a traditional house, Lakaz Roza, decorated by children from Heritage Clubs organised by the Seychelles Heritage Foundation

Certain styles of clothing and décor are still part of what it means to be Seychellois, both in Seychelles and abroad. A classic bourgeois Seychellois sitting room will have a large wooden sideboard (nowadays with a TV occupying a central space), filled with ornaments, mementoes and family photos. The low coffee table will be covered with an embroidered or crocheted cloth, and the chairs and sofa will have sturdy wooden frames and be constructed in such a way that you have no choice but to loll in them.

In my initial fieldwork in London, I found it touching that so many interlocutors reproduced elements of this kind of sitting room in their small London flats, and often had a few souvenirs from Seychelles placed prominently; in these elements, I recognised my own mother’s sitting room, her own souvenirs and trinkets. These decorative flourishes had been detached from their original meaning as signifiers of cosmopolitanism, modernity, and whiteness. In London, they became quaint, old-world, and sentimental, and represented a national and ethnic identity that, outside the house or flat, would require reinterpretation in line with British understandings of race. “What are you?” some informants had been asked, by Brits who had heard of Seychelles only as a luxury holiday destination.

Inside, this question was irrelevant – it was fine simply to be Seychellois.

In Seychelles, I found that sitting rooms were filling up with the detritus of a new cosmopolitanism: Chinese-made appliances, decorative touches cribbed from American soaps and Latin American telenovelas. The classic sitting room was as old-fashioned and sentimental as it had been in London, but how informants felt towards it was different – it was beloved but in the process of being reshaped by Seychellois who aspired to be modern and stylish. This was a complicated negotiation, producing mixed feelings; an informant lamented to me that “we pick up every new thing, we don’t ask if it’s good or bad.”

My own standpoint as an anthropologist meant that I balked at the idea of “culture” being “lost”, and tried repeatedly to stress to informants that I was interested in change and compromise as much as a static picture of the past (of which I would naturally have been suspicious). But in working with the Ministry of Culture and with visual artists, I was drawn inexorably into the idea of heritage that Seychellois were working with: a model in which material traces of the past had to be preserved and or, where they did not exist, created.

Artists across art-forms, but particularly in the realm of the visual, were always working in dialogue with this idea of the past.

The trappings of everyday life, the signs of a respectable traditional household, had significance for diverse reasons.

For the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, they were important in terms of their economic value as well as their cultural value. Many Seychellois artists had learned traditional art and craft techniques as part of their formal art education, and had gone on to teach them to the younger generation. These techniques had formed the backbone of the souvenir industry in the latter half of the 20th century, but are now being displaced by mass-production.

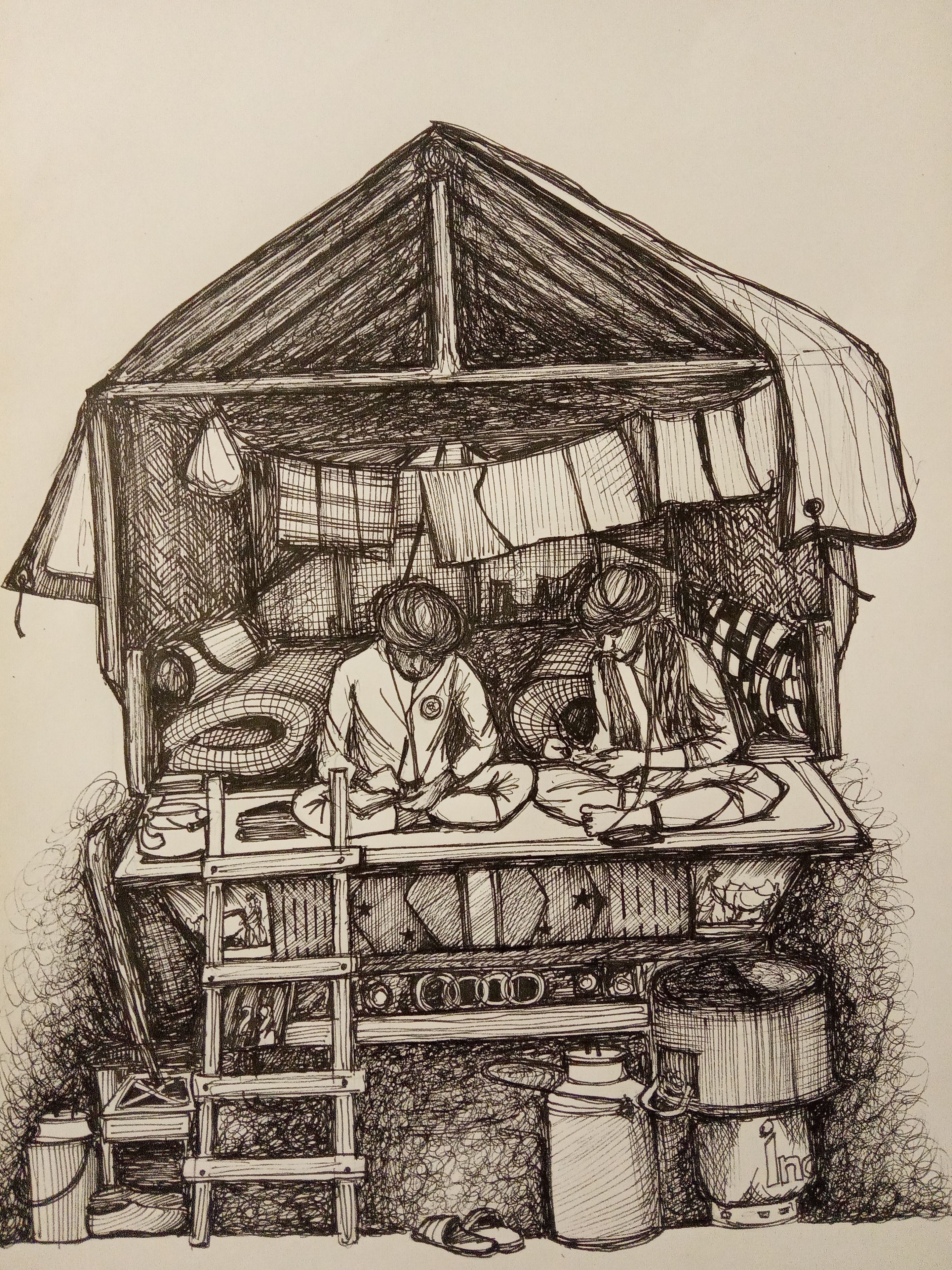

The Craft Village, at Domaine Val des Pres, where artisans sell craft objects for tourist consumption

But craft was also necessary for maintaining a connection to “heritage.”

Informants within the heritage sector were passionate about imparting a knowledge of weaving, gardening and cooking to children, as it was these aspects of daily life that they worried would become “lost”. The gran kaz itself served as a monument to colonial aspirations and technologies, but the daily life of common people was less tangible. Craft and domesticity served as an idiom through which the plantation-centred past could be communicated to children who were very young; without lingering on the violence of slavery, informants could emphasise the resourcefulness and resilience of Seychellois. In the process, objects were created that could embody these values.

During October, in the run-up to the international Festival Kreol, young (school-aged) artists were invited to participate in a competition, creating two- and three-dimensional works on the topic of “traditional life.” A historian from the Ministry delivered a presentation, and young people produced imaginative works featuring women washing clothes in the river, the collage of magazine clippings decorating a traditional house, or household implements made from wood and coconut shell.

Young artists’ competition entries exhibited during Festival Kreol 2016

“Craft” and “art” were often intertwined with one another in heritage discourses, so that actors continually had to negotiate the boundary between the two. The women enlisted to teach children how to weave coconut leaves were identified as “artisans”, and their knowledge was described in terms of its authenticity – the extent to which it reproduced a particular idea of the domestic past. But the value of these techniques was treated economic and aesthetic, not artistic.

Craft was associated with the household and the past, and therefore limited in its contribution to a larger body of artistic knowledge, and a more ‘public’, global modernity.

The distinction for many artists who utilise craft techniques is that their work is “archival,” implying not reproduction but historicism. In the work of artists such as Egbert Marday, Leon Radegonde, Colbert Nourrice and Jude Ally, craft techniques are incorporated into painted canvases and assemblages of found objects in order to represent processes of memory and nostalgia. Christine Chetty-Payet’s textile-based pieces explore the social construction of femininity through weaving and embroidery, and place African women at the centre of creative consciousness in a way that is tangible rather than metaphorical. Each in their own way approaches craft as subject, as well as method.

However, in practice the boundary was blurred.

Marie-Reine Mahoune’s elaborately pretty painted silks and embroidery were exhibited alongside more overtly concept-driven work in the 2016 Festival Kreol National Gallery exhibition, placing them firmly within the context of international art. Artists and artisans participate in the same events, join the same associations, and engage in similar processes of engagement with the past. Craft facilitates engagement with the past. It renders the reality of the plantation and its legacies less vast and horrifying, emphasising the resourcefulness and respectability of Seychellois as they negotiated racial and social hierarchies. For artists working in a fine art milieu, or within an international context of biennials and art fairs in which Seychelles is a relatively disadvantaged participant, the idea of this resourcefulness is still hugely significant.

In thinking through all of this, I have considered how I myself might express these relationships visually, since visuality was so central to my experiences in the field.

I had a realisation, near the beginning of fieldwork, that I had unknowingly been involved in many of the same processes as my informants: my mother had taught me how to cross-stitch, embroider, quilt, and sew from a young age. This realisation, as well as the techniques themselves, connects me to an experience of postcolonial diaspora that I share with others (Checinksa, 2015).

It seems necessary to actually use these techniques as I think about how they have moved between inside and outside, female and male, respectability and reputation – and in this movement, have highlighted the porousness of these boundaries. I am beginning by sketching traditional household objects, just as the young artists did. I plot pieces that I will cross-stitch, I practice different forms of embroidery after a day of writing. I think about the ways that I could use the textures of thread and fabric to produce prints, what it would mean to ‘translate’ embroidery in this way. I seek to produce art while writing my thesis, without being sure of whether it will be used instrumentally, to convey ethnographic data to peers or examiners. All I know is that when I look at the objects I have made, I will understand better what I am doing, and that in showing them to Seychellois who so readily shared their own beautiful things with me, we might continue a dialogue about art and the past.

References:

Benedict, B, & Benedict, M. 1982. Men, Women, and Money in Seychelles. London: University of California Press

Checinksa, C. 2015. Crafting difference: art, cloth and the African diasporas. In Cultural Threads: Transnational Textiles Today, ed. Hemmings, J. London: Bloomsbury. pp.144-167

Miller, D. 2010. Stuff. Cambridge: Polity

Wilson, P. 1969. Reputation and respectability: a suggestion for Caribbean ethnology. Man, 4(1), pp.70-84

Wilson, P. 1973. Crab antics : the social anthropology of English-speaking Negro societies of the Caribbean. New Haven: Yale University Press

All photos courtesy of Mairi O’Gorman.