After a week of performed ethnographic poetry, Robert Desjarlais and Eileen Moyer wrap things up in their concluding remarks. If you haven’t read the posts yet, go back and start from the beginning. It’s worth it!

Imagine Further

by Robert Desjarlais

Imagine yourself suddenly set down in a small theatre hall near a slow-moving canal at the University of Amsterdam one Friday morning in early June. There are signs that a music performance took place there the night before, chairs left here and there, electronic equipment in black boxes, a skinny microphone stands on an empty stage. Today, the room will be used for a rather unique event, an ethnography slam, with a number of participants performing words, sounds, and images drawn from the tonalities of their fieldwork in places as diverse as Kenya, Indonesia, India, France, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Imagine further that most here are beginners, without previous experience, with little to guide them. People start to arrive, hesitantly, curious, filled with anticipation. They are carrying notebooks, pieces of papers, cups of coffee. They sit shyly in the audience, waiting for the first performance. The organizers of the event, courageous in their inventive effort, get things going by welcoming all those in attendance and encouraging the participants to speak freely, creatively, without concern for judgement or the formal constraints of academic writing.

The first performer takes the stage, the mood quiets, and spoken words resound through the room. We’re being brought into the intricacies of a fieldwork encounter, but this is no dry piece of scholarship, there’s no thesis argument or analytic frame or comprehensive body of research advanced for the sake of anthropological knowledge.

What there is, instead, is a taut play of dialogue and reflection that gets at a moment keenly real.

These words come to a close, the first performance is a success, there’s relief in that, and slight surprise, and in the room along with a round of warm applause there is the faint but emerging sense that something different is at hand, charged, vast, unordinary.

The second performer takes the stage, and the next, still others follow, and with each of these immersive engagements we enter into select worlds of language, silence, stillness, relation, unspoken pain. The themes come like litanies of existence, tearing into what’s at stake in the lives of those known through research encounters as well as what’s crucially involved in the researchers’ relations with them.

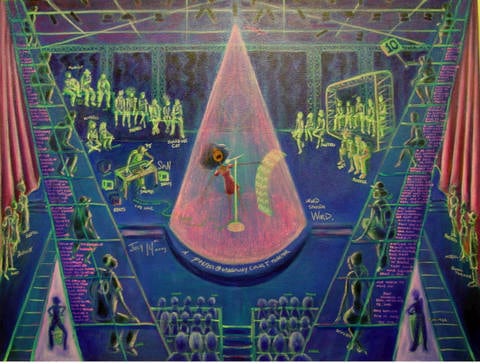

Photo by Lyndon (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Through a mosaic of words we learn about the concerns surrounding a young man hooked on heroin in Indonesia, Joshua is a good guy, his brother-in-law tells me…If he really wanted to put and put his mind to it, he could recover but… We hear the playful, knowing rhymes of the Daktari, from Nairobi, I’m kinda tired of WHO/ Telling me what to do. We hear the words of an elderly woman stricken with dementia and the researcher who accompanied her in walks in hallways, I tried to relate to Ms Lichthart by talking to her although I did not understand her, by repeating her words… We encounter the lifeworld of an elderly woman being cared for by others, the older you get, the more you are still… the wash cloth touches your face and moves to your left cheek… We approach but can never comprehend fully the concerns of an admirable young woman struggling with a muscle disorder, Instead of a perfect response, I would prefer some vulnerability. We learn of an elderly woman who is considering her possible death through euthanasia, or by her own hand, she might still have the problem that she might have wanted to die, but didn’t know how to. We come to know of a woman who died of cancer and the researcher and friend who cared for her through the days of her dying, These are strange love stories, because we engage and follow, and open up and hardly draw boundaries.

These are strange ethnographies that we are hearing, for in skirting the scholarly and professional demands of academic writing, in forgetting those constraints for a week or a morning, the performances open up our thinking on the lives and yearnings of those subjects who cannot be reduced to orderly, well-reasoned tracts of interpretation.

The room is coming alive now with life in all its varied textures and tones, at once incisive, disordered, painful, moving, haunting. The energy of a particular scene or word, acts of encountering or listening to another, is with us now. And it’s not just the lives of the subjects of the performed texts which are coming to our attention, be they the residents of nursing homes or schools or neighborhoods in far-off cities. We’re also sensing the lives of the performers themselves, these vulnerable, spirited persons on the stage, performing alone or ensemble, many of them at the start of promising careers, learning to write for the discipline, trying to locate their voice in writing, unsure of what is possible or permitted, and finding in the texts they penned through the week, in the midst of a writing session or drawn from their fieldnotes, an encounter that transfixed them. They’re finding in these chords a voice that goes beyond what they have written to date, a poetic voice that seems to sing out to the world, beyond anything intended or anticipated that morning; and the sudden fact of this creative, emergent act, this poiesis on the spot, moves and surprises them, and us, speakers and audience members alike find themselves thrown into the emotive and imaginative charge of the performances, as if we’re suddenly faced with a collective rite of transformation where the world and its subjects are starting to look different, and with this the potentialities of fieldwork and ethnographic writing take on renewed significance.

Imagine that ethnography, etymologically, is the writing of a people, the graphic trace of a way of a life, and that the graph of such writing usually takes form in the space of the printed page. Imagine further that the morning’s performances led those in attendance to appreciate the ways in which ethnographic writing can go beyond the printed page and work otherwise than the well-honed channels of analysis and get at features of life in ways that disturb and alter the idea, the very graph, of ethnographic writing.

The Pleasures of Academic Life

by Eileen Moyer

The pleasures of academic life are many. Getting paid to read books I like, to hold conversations with people from life worlds radically different from my own, and to contemplate creative modes of sharing what I learn in the process: writing, filmmaking, photography. I really do think it is amazing that such a profession exists, and I try to remind myself from time to time to be grateful that I get to live this life. There are moments, however, when no reminder is needed, when I’m simply overwhelmed by the joy of what I do.

In the past few months I have had the pleasure of being knocked flat, more than once, by the pleasure of watching PhD students and colleagues bravely experiment with new writing voices and tackling the tough, emotional topics that so often remain beyond the pale in academic writing.

This pleasure—well, pleasures really—emanate from an ethnographic writing workshop in which I was recently involved as organizer, lecturer, workshop leader, and audience member. The first pleasure came when the student co-organizers, Tanja Ahlin and Silke Hoppe, approached me in mid-2015 to propose that I work with them on “some kind of writing class for PhDs.” Like them, I thought it strange that students were offered so little guidance on writing at the University of Amsterdam. Given that we are so often told that the thing we do most as anthropologists is write, one would think that more time, money and effort would go into thinking about and teaching techniques of ethnographic writing. Because much of my work is, like Tanja’s and Silke’s, situated in medical anthropology and science and technology studies, it also seemed to me that some sort of coaching should be made available to students who were expected to write for multiple audiences in the domains of (medical) anthropology, public health, global health and health policy. In our department, students also have the possibility of writing a dissertation based on articles or a book-length manuscript, yet they are not given training in these different modes of writing.

Photo by Liam Kearney (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Having previously taught a course on ethnographic writing that was cut due to budgetary constraints—despite students rating the class highly and asking that it be taught again—I was truly pleased when Tanja and Silke approached me to organize ‘something’ to address their desires to improve their writing. Although I was not thrilled that we were expected to do this ‘extra-curricularly,’ in our own time, I was happy to hear that there was a small fund we could draw upon to invite external lecturers. Together, we drew up a proposal that was eventually funded, we identified and invited two great writers of ethnography known for their generosity toward students (Julie Livingston and Robert Desjarlais), and began to plan the workshop. We knew we wanted to keep the class size small, so that we could workshop the writing in the way creative writing courses do. Given the great demand (more than 30 people signed up in a week!) we decided to offer plenary lectures in the morning and work in three groups of 10 (eventually 11 to accommodate the desperate to attend) to workshop ideas and writing samples in the late morning and afternoons.

For me, the workshop offered many additional pleasures, and I’m not just talking about the nice food in the beautiful Villa Mattern. Most importantly, I enjoyed getting to know the PhDs better. In my day to day work, I tend to focus most of my energy on ‘my’ PhDs, which brings its own pleasures, but hearing about the projects of other PhDs in the department made me more aware of the depth and breadth of our department.

I listened with wide open ears as students talked about their struggles to write up the densely packed ethnographic research materials they had collected.

We laughed and cried together as people shared paragraphs about chronic illness, growing old, physical impairment, drug addiction, loneliness, loss, love and death. Others, first year students mostly, attempted to develop an ethnographic voice that sounded both reflexive and informed. All in all, scary business. I was at times overwhelmed by the bravery of students who dared to experiment if front of their peers, not all of whom were friends.

Nothing, however, prepared me for the greatest pleasure of all: The Friday morning Ethnography Slam Event! Although we had conceived the event as a way to get people to experiment with writing styles and to practice performing rather than simply presenting their research, the truth is, we didn’t really think too much about it. Or at least I didn’t. I rather suppose that Tanja and Silke did a lot more work on this front. I remember that on the morning of the event I drank a triple espresso before leaving the house, assuming that I was going to have to work hard to appear attentive during the four hours of scheduled back-to-back presentations in front of me. The night before, most of us had had a bit too much to drink at the closing social event of the week, and I was certainly a bit foggy brained. I’d been warned in advance from several participants that I should not expect much. I was told some people were even angry at me (at me??) for insisting that they perform publicly, that they didn’t feel safe. Also, they didn’t have time to prepare; the night before over drinks nearly everyone said they weren’t at all ready.

Photo by Zeal Harris (flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Yet, from the first presentation, I was enthralled. I felt like a proud parent as writer after writer got up and performed—yes, PERFORMED—his or her ethnographically-informed theatre piece. Poems, multi-media presentations, short essays and just-so stories delivered with great ceremony and aplomb. Who ARE these people, I wondered? Are these really my students, my colleagues? Are these the people I pass in the hallway and nod at? The people I chat with at the coffee machine about methods and deadlines? Before the first hour was up, my phone and Cloud storage was full. No more room for videos and photos. Devastating. Devastating beauty, that is. When the performances came to an end, Tanja asked me if I or one of the other lecturers/teachers would say a few words, to reflect on the day.

But there were no words. We all agreed. It was impossible to follow such exceptional talent, emotion, and bravery with a mundane academic round-up.

The pleasure did not end there. In the days and weeks following the workshop, I was regularly approached my participants and their PhD supervisors. It seemed the effects of the workshop were already visible in dissertation and article manuscripts, that students who had been blocked before the workshop were finally writing again. Many were even enjoying it. Recently, I had the chance to watch one of the workshop participants deliver a paper-academic style. I felt deeply proud (even had a tear in my eye) as she opened with a vignette that she had begun crafting in my workshop a few months earlier. She’d honed it to perfection and everyone was on the edge of their seat. How grateful I am to have played a small role in helping an amazing woman find her voice and gain the confidence to use it. The definition of pleasure.

Featured image (cropped) by Carla de Souza Campos (flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)