When the picture of Alan Kurdi’s drowned body first hit the headlines, it was instantly iconic. For many, the simple horror of the image suddenly made the refugee crisis real – and galvanised a moral and political will to respond. World leaders expressed sympathy and dismay, or defended their asylum regimes; initiatives to collect and transport clothes, blankets, and food sprang up across Europe, and donations to aid organisations skyrocketed.

Before the year’s end, the same image appeared in a highly controversial Charlie Hebdo cartoon satirizing sexual assaults widely attributed to refugees in Cologne. Above an image of pig-snouted men, with their tongues lolling and their hands groping after screaming women, it invited its audience to imagine what Alan Kurdi would have grown up to be. The outrage stirred by the cartoon clashed with the outrage caused by the assaults, in a context of growing discord around how Europe ought to respond to the unfolding crisis. Hebdo’s reimagining of Kurdi as an adult rendered him a threat, even after his death; cartoons drawn in response, emphasising his foreclosed futures as a father, or doctor, reasserted a counter-narrative mourning lost hope and frustrated potential for good.

The catalogue of similar images of children in crisis is as long and varied as the history of political conflict and humanitarian disaster – ranging from the naked, napalmed girl in Vietnam, to the Ethiopian child collapsing with starvation in front of a watchful vulture.

Images of suffering and endangered children shape our imagination of disaster perhaps more powerfully than any other, and continue to generate moral and political obligations to respond.

At the same time, images of children are especially prone to drastic shifts in interpretation; and the repercussions of our response are often equally fraught, ambivalent, and unpredictable.

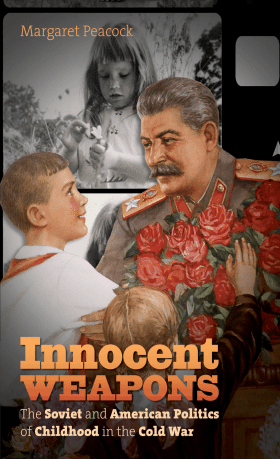

The real battle lines of the Cold War, she concludes, lay not between capitalism and communism, nor between America and the Soviet Union, but between the producers of discourse – the ‘architects of consensus’ (p. 223) – and their intended audiences.

Gradually, however, inconsistencies between the ideals portrayed through such representations and the lived reality of the Cold War became too glaring – in America, the Soviet Union, and the battlegrounds of Vietnam. Peacock demonstrates that similar representations of children then became the major means of satirising, destabilising, and resisting the Cold War consensus – whether through satirical film, propaganda flyers, or nationwide advertising campaigns and activism. The same means of generating consensus, in other words, were used to destroy it; and the shared experience of conflict generated a newly-oriented consensus in its place.

In constructing this argument, Peacock’s comparisons sometimes feel stretched – Part II sets an analysis of American milk boycotts, conducted to protest atmospheric nuclear testing, against close interpretations of Soviet films produced during Khrushchev’s Thaw – but their juxtaposition draws out their differences and specificities, while highlighting uncanny connections. The result is a compelling proof that ‘[t]he construction of Cold War kids was a shared project that crossed the East-West divide’ (p. 222), in many ways produced it, and ultimately deconstructed it.

While Peacock’s work is primarily historical, it offers a range of insights for anthropologists. In it, for example, we find one provenance of the universalised, idealised child to which much contemporary humanitarian discourse is oriented. Liisa Malkki (2010) describes humanitarian representations of the child in very similar terms – as embodiments of goodness, as sufferers, as seers of truth, as ambassadors of peace, and as embodiments of the future – and argues that these representations are deployed to produce a global community. The explicitly apolitical affect evoked, its deliberate political aims, and its unpredictable effects, all resonate deeply with the insights of Innocent Weapons. To this extent, Peacock’s work provides a perspective on the ways humanitarian projects – especially those dealing with children – might be unsettled and disrupted by the very images through which they justify their interventions.

Peacock is explicit that her work is ‘not about real children’ (2014,1). And yet it is, perhaps inescapably so. Some of the best passages in the book resonate precisely because they are about real children and real people: ten-year-old Svetlana Zhiltsova, for instance, nervous for her speech to the Eleventh Congress of the Komsomol, and her later reappearance as the irreverent, provocative host of a youth television programme; or the protestors of Women Strike for Peace, with their children in tow, disrupting proceedings when called to testify at the House Un-American Activities Committee.

What these passages bring out so strongly, without engaging it directly, is the political agency of children and youth.

That Czech protestors as young as ten not only took to the streets in protest against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, but triggered trepidation at the highest levels of political leadership across the Eastern Bloc when they did so (p. 219), underlines the extent to which children and youth were – and are – a real, and highly volatile, political force. Peacock effectively challenges anthropological portrayals of childhood as strictly culture-bound (see, i.e., Lancy 2008), prioritising the effects of socio-political context. But she stops short of examining the disjunctions between the unstable images of childhood, and the behaviour and reactions of actual children – in spite of presenting material richly suggestive of those disjunctions. Might such sharp inconsistencies have been as destabilising of the Cold War consensus as the indeterminate image of childhood itself, or moreso?

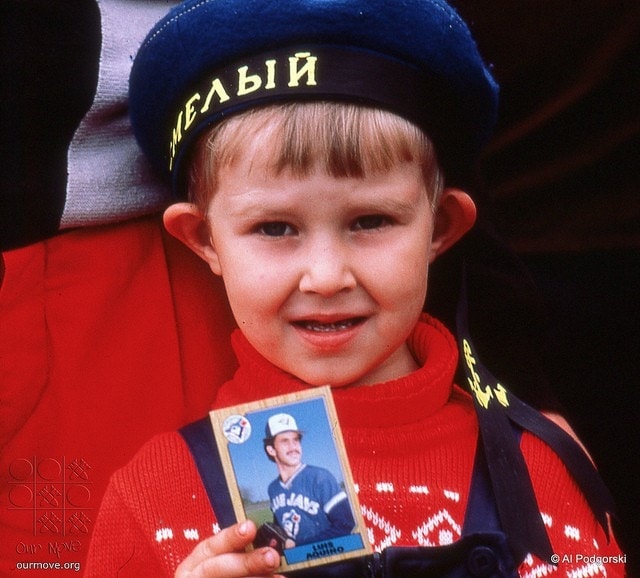

Photo by Our Move Archives (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

There is another notable silence in Peacock’s account – which is perhaps as much about Soviet and American portrayals of the family, as it is about portrayals of children. Renderings of children as innocent or dangerous, redemptive or destructive are tied tightly to the presence or absence of families, and their capacity to care for and contain their offspring. As the Cold War dragged on, Peacock notes that ‘rising delinquency rates’ emerged as a central concern for both America and the Soviet Union; and in both cases, it was ‘blamed on negligent parents’, helping ‘to justify a new form of state intervention in private life’ (2014, 90). Where purportedly deadbeat dads and coddling moms were unable to provide the sort of upbringing the nation needed, the nation stepped in: everything from parenting manuals to state-linked organisations like the Boy Scouts and Pioneers became means of policing, rehabilitating, and mobilising parents, positioning the state as a sort of surrogate parent in turn. There is a parallel story to be told here, about the sort of power the family instantiates and represents, and the ways the state models itself upon and attempts to appropriate that power. While it doesn’t pursue these possibilities, Innocent Weapons points to a rich avenue of investigation for anthropologists to follow, supplying a wealth of historical perspective and context for such an endeavour.

Peacock’s book leaves us with a deeply uneasy sense of the political polyvalence of children and childhood – not simply during the Cold War, but for our contemporary political moment, as well.

The image of Alan Kurdi generated an outpouring of humanitarian aid, taking goods and volunteers to refugee landing zones and informal settlements from Lesvos to Calais. By the same token – as prefigured by the Hebdo cartoon – his washed-up body has come to symbolise a threatening transgression, ‘an eschatological emblem of all that could not be protected’ (p. 225): children, refugees, and borders alike. And that transgression underpins new and ugly fears, articulated in the send-them-home rhetoric of the Republican race in the United States, or the take-our-country-back rhetoric that recently won a Leave victory in Britain’s EU referendum. The murder of MP Jo Cox in the lead-up to the latter vote remains murky in its motivations, but her advocacy for child refugees was well-known. While the significations and actions of children in times of political precarity may be too unstable to offer a sense of what is to come, they may show us how and where the battle lines are being drawn – and may remind us that those battle lines conceal other, deeper, and widely shared mechanisms of reproducing power and inequality.

References:

Lancy, David. 2008. The Anthropology of Childhood: Cherubs, Chattel, Changelings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Malkki, L. 2010. Children, Humanity, and the Infantilisation of Peace. In In the Name of Humanity: The Government of Threat and Care, eds. I. Feldman and M. Ticktin. Durham: Duke University Press.

Peacock, Margaret. 2014. Innocent Weapons: The Soviet and American Politics of Childhood in the Cold War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 304 pp. Cloth: $34.95. ISBN: 978-1-4696-1857-9

**********

Featured image by BrunoBrunan (flickr, CC BY 2.0)