While media attention is focused elsewhere, a new phase of the “European border crisis” is unfolding around the snow-covered mountain passes between Italy and France. What might the experience of the African migrants there, and of the activists trying to help them, tell us about the social life of intra-European borders today? This post explores this question, moving in two instalments. Part 1 draws on an encounter with migrants in an Italian border town. Part 2 examines the politics of local pro-migrant activism.

It’s a frosty February night in Bardonecchia, a skiing resort in Val Susa, some ninety kilometres west of Turin. The doors to the waiting hall at the train station are locked. ‘The management kindly informs that only holders of a valid railway ticket are permitted to stay on these premises’, reads a note. The room where the migrants are, in another wing of the building, is small and undecorated, with yellowish-painted walls and ochre floor-tiles. It is fluorescent-lit and stuffy, but stuffy is good, stuffy is warm, with radiators working full steam. In one corner, orange camp-beds on aluminium frames are stacked. In another, there’s a heap of blankets, and two pairs of boots are drying under the radiator. The third corner is occupied by a thick mattress on which three men are sitting, doing nothing much: glancing at their phones, talking intermittently. Others are squatting by the walls, next to the power sockets, waiting for their phones to charge. Sitting on chairs. Listening to music on their headphones. Walking out and back in. Waiting. On the whole, there’s ten of them here tonight, all men, young, between their late teens and perhaps early thirties, all from sub-Saharan Africa. Phones are ringing all the time. The migrants talk in a mixture of tongues I don’t understand, among which I only recognize French, spoken with an accent I’m unable to tune in to. Two men are squatting around a phone watching a football game. It’s Paris Saint Germain against Real Madrid. A goal is scored. A half of the room cheers, the rest seems indifferent.

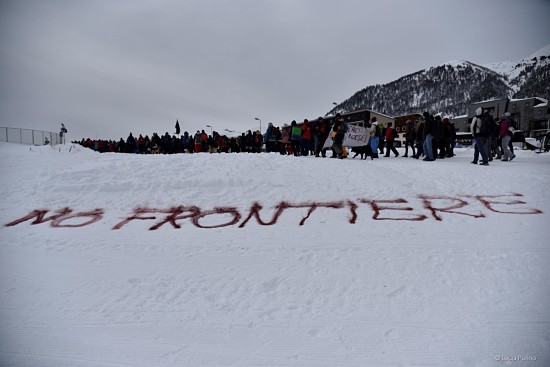

Since the border crossing between Italy and France at Ventimiglia, on the Azure Coast, was shut down in 2017, Val Susa has emerged as the main route for African migrants trying to cross from Italy into France. Throughout this winter, between five and fifty migrants have attempted the snow-covered mountain passes every day. According to Rainbow4Africa, a humanitarian organization helping the migrants, one thousand people were rescued in Val Susa between December 2017 and March 2018. As local activists stress, however, a full-blown ‘emergency’ is likely to erupt in spring, when the snow melts. So far, there hasn’t been any consistent response by the Italian state, but diverse networks of activists are trying to confront this unfolding conjuncture, while a cottage industry of illegal parasitic passeurs has been quick to develop. The irony of this situation lies in the fact that Val Susa is Italy’s perennial gate to the Transalpinum: it was through here that Hannibal entered Italy with his elephants in 218 BC, and Julius Caesar crossed in the opposite direction a century and a half later. As an anthropologist, I have never studied borders or migration, and I ‘stumbled’ upon this topic while doing research in Val Susa on something else, so my knowledge is very limited and my claims must be modest. However, glimpses from this emerging next episode in the ongoing ‘European border crisis’ (for a critique of this notion, see Cabot 2015) suggest insights on the social life of borders and their violence.

I’ve come to Bardonecchia with three members of a local youth activist group who come here every Wednesday night to bring food and drink, and see if anyone might need more help. They coordinate with other groups who cover other days of the week. After a while, a Rainbow4Africa team arrives, headed by Pietro and Leo.[1] Pietro is a short middle-aged man, wearing a yellow high-visibility vest that reads ‘DOCTOR’ across the back. Leo comes from West Africa, but has lived in Italy for a long time. He’s a ‘cultural mediator’: he talks to African migrants, trying to understand what they’re up to and persuade them to accept help. The two greet us and shake hands with several of the African men. Pietro taps one young man on the shoulder and, turning towards us, says: ‘He wants to go to France to join a football school. He wants to be a star player.’ A broad bright smile flickers across the young man’s face. Leo describes the situation tonight as ‘calm’. Just ten men and no emergencies. But then one of the young activists receives a text message: there are twenty more people, including women with small babies, at Claviere. They’re determined to cross over to France and refuse even to consider any other option.

Bardonecchia is the last station before the border on the railway line from Turin to the French town of Modane. From here, migrants hope to cross to France, but it takes a long mountain hike through deep snow and a climb to the Colle della Scala pass. It’s avalanche season now and the trails are impassable. So, many migrants hitchhike or take the bus to Claviere, a tiny mountain town located right on the border, sixteen kilometres off the railway track. They are often intercepted by passeurs—usually Moroccans, Albanians or sometimes Black Africans, more rarely Italians—who charge several hundred Euros per person for information about the trail and possibly phone numbers of their counterparts on the French side. The passeurs operate in a grey zone they share with human-traffickers and slave-trade intermediaries. Apparently, at refugee centres in central and southern Italy, as well as the country’s railway hubs, it is possible to purchase a smartphone app, at one hundred Euros per download, containing a detailed map of the route from Turin, via Bardonecchia and Claviere, into France. The map includes information about the points where migrants can find food and shelter provided by activists. Thus, inadvertently, the activists become a part of the package the passeurs sell. Locally, a transportation company owned by an individual known to activists as a right-winger and opportunistic money-monger runs a shuttle van to Claviere. Activists are uncertain whether the guy is a freelancer or part of the passeur-coordinated package.

Photo by Luca Perino

From Claviere, it’s three kilometres along a cross-country skiing track to Montgenèvre, already in France. As Leo points out, the migrants have crossed the Sahara; escaped war or famine, or both; many have been through the prisons and slave camps in Libya; and finally they crossed the sea to reach Italian shores. ‘Do you think that mountain there, that snow, can stop me?’ they ask with irreverence. But the mountain is unrelenting. The image of a white sneaker lost by a migrant in the snow on the Claviere route has been circulating in activist social media. The sneakers are becoming a symbol akin to the orange life-vests floating in the Mediterranean. And the mountain is not alone in stopping the migrants. The French Gendarmerie routinely intercepts them and returns them to Italy. It seems that the French and Italian ‘forces of order’ prefer to avoid more conspicuous presence and mass confrontation, as earlier in Ventimiglia and Calais, while the skiing season is on. However, less spectacular push-back violence is routine. Sometimes, activists say, even migrants captured many miles inside France are brought by the gendarmerie to Bardonecchia, as the gendarmes know about the volunteer-run room there and they seek to easily get rid of the burdensome workload the migrants are to them. In late March, a Nigerian woman died following childbirth, after being captured by the French gendarmes and dumped at the Bardonecchia station. In Claviere, there is no shelter at all, so migrants returned from the skiing trail must spend the night outside.

A Spanish TV journalist materializes in the meantime. He tries to talk to some of the migrants. He picks out a young boy who understands some Italian and English. The boy answers the journalist’s questions with half-sentences and an expression of utter boredom on his face. He says he’s nineteen and comes from The Gambia. He wants to go to England where he says he has ‘family’. What family, he’s unable to say. ‘How do you want to cross to England?’ the journalist asks. The boy shrugs. ‘Do you want to pass through Calais?’ Another shrug. ‘But Calais is very dangerous, do you know that?’ The boy looks up, points his finger at the ceiling and mutters, ‘He will help me.’ Who will help you? ‘What’s the word? In Italian…?’ the lad asks. ‘Dio’, I offer, ‘God’. ‘Yes, zio’, the boy nods—‘uncle’.

Another of the African men shows me his phone with a car-sharing app running: ‘Can you help me find a ride from here to Paris?’ Paris is eight hundred kilometres away, but step by step I begin to understand that it’s not necessarily Paris that he wants—it’s just the only place in France he knows. I realize he speaks almost perfect Italian. ‘Have you been here for long?’ I ask. Seven years, he says. I’m surprised, but Pietro and Leo tell me that’s not unusual. ‘That other guy there’, they say, ‘has been here for five years.’ Actually, none of the men who are here tonight has lived in Italy for less than a year and a half, in and out of various forms of detention, employment, shelter. The migrants’ fates after arrival in Italy vary. Some end up de facto enslaved in mafia-run labour camps (Giordano 2016). Many are taken care of by private-run co-operatives paid by the government to provide shelter and food. Many of these co-operatives are honest, but there are also frequent complaints about places allegedly controlled by the mafia where the conditions are dismal while the management siphons off the government-allocated funds. Other migrants are placed in housing managed by municipalities across Italy. Still others make it into NGO-run ‘hospitality centres’ where they receive food and lodging, some pocket money and help finding jobs. According to the activists I talked to, conditions in these centres are generally good, but many migrants leave to try their luck passing over to France. The gamble is that once you’ve been out of a hospitality centre for seventy-two hours, you won’t be admitted back.

‘Why do you want to go to France?’ I ask. The man says, ‘Because I have an appointment in Berlin.’ This doesn’t make sense to me, but he asks me if I speak German. I nod for yes, uncertainly, and he shows me a document from the German office for aliens’ affairs in Berlin, inviting him, Abdou K., a national of Mali, to an interview in exactly one week’s time, at 9 am. I don’t quite understand the German legal jargon of the document, but from what Abdou carefully explains to me, I begin to gather a story. Having arrived in Italy in 2011, Abdou obtained a residence permit. In 2013, for reasons I don’t quite understand, he went to Berlin. There, in collaboration with a local church he launched an association to help other migrants. He stayed in Berlin for almost four years. But in December 2016, his residence permit was running out. Abdou travelled back to Italy to have it extended and filed a request with the relevant office in Turin. Since then, the only response he’s had has been that he should wait. Without a valid permit, Abdou is unable to cross intra-European borders legally. I don’t quite understand what his interview in Berlin is about, but he shows me messages from his association that urge him to come back. Somehow, the future of the association depends on his presence. Ich muss es schaffen! Abdou insists, suddenly switching into an almost accent-less German.

This vignette sheds light on the migrants’ experience of the European border regime.

While the focus of critical literature (e.g., Cabot 2014; Vaughan-Williams 2015; Fernando and Giordano 2016) has often been on borders implicitly as lines, such as the coastline, or peripheral zones of the EU, it seems that for migrants ‘the border’ is a socio-political and existential condition that extends across vast geographical spaces.

All of Italy, with its detention centres, farms, shelters and train stations, becomes a border. Borders in that sense are not simply crossed, but rather dwelt in like a limbo, sometimes for years. My account of the young Gambian migrant above is by no means intended to invite ridicule, but rather to convey the cruelty, and the human tragedy, of a situation where people like him risk their lives pursuing a vague vision of a place finally beyond the ‘border’ where one can live better—in this case, an imagined ‘England’. But Abdou’s story indicates that under the Dublin Regulation, the border cannot ever be crossed once and for all. Abdou did everything he was supposed to in order to be ‘legal’ in Europe, and then more. But he’s trapped in this transnational bureaucratic quagmire, dropped into ‘undocumentedness’, deportability and hence also clandestinity. The crossing of no particular line frees one from the border. Moreover, the vignette above evokes a multiplicity of actors who generate and inhabit ‘the border’. The next instalment of my notes focuses on their relations.

Works cited

Cabot, Heath. 2014. On the Doorstep of Europe: Asylum and Citizenship in Greece. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

‑‑‑‑‑. 2015. ‘Crisis and Continuity: A Critical Look at the “European Refugee Crisis”’. Allegra Lab, November 10, 2015. https://allegralaboratory.net/crisis-and-continuity-a-critical-look-at-the-european-refugee-crisis/

Fernando, Mayanthi and Giordano, Cristiana. 2016. “Introduction: Refugees and the Crisis of Europe.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, June 28, 2016. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/900-introduction-refugees-and-the-crisis-of-europe

Giordano, Cristiana. 2016. “Catastrophes.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, June 28, 2016.

Vaughan-Williams, Nick. 2015. Europe’s Border Crisis: Biopolitical Security and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[1] All individuals’ names have been changed.

This research was financed by the National Science Centre (Narodowe Centrum Nauki) within the framework of the postdoctoral research grant programme, grant no. DEC-2013/08/S/HS3/00277.