Hautalk is an opportunity to reinvigorate and remake our disciplinary identities. But how can we move this discussion beyond disciplinary boundaries—into spaces where we practice our craft? This essay makes the case for refashioning anthropology to re-imagine our labour practices outside academia as a form of principled engagement.

I do not think it would be erroneous to say that there has been a proliferation of discussions around #hautalk over the last several weeks. This hashtag—now a shorthand, really—has come to refer to the specific allegations of physical and emotional abuse, misappropriation, and misconduct made by former Hau staffers against the journal’s now-suspended editor-in-chief, Giovanni Da Col; the attempts to cover up the controversy, which Hau’s editorial board referred to as “destabilizing efforts” early on; and, the discussions around precarity, workspace abuse, and the persistent problem of coloniality, sexism, and other forms of disempowerments within the discipline.

This discussion has included some brilliant, incisive, and thoughtful responses: Anand Pandian’s mediations on openness, LaFlamme and others’ on open access, and Jason Jackson on scale; Zoe Todd’s call for decolonizing and radically reimagining the discipline, and Mahi Tahi’s incisive critique of colonial appropriation; Ilana Gershon on the structures of exploitation like pyramid schemes, which enable such abuse to take place, by rewarding “assholes,” as Elizabeth Dunn writes; or how, Nayanika Mathur reminds us, we are complicit in such silences; and efforts to redirect energies towards engendering relations of respect and care in collaborative work.

As an early career anthropologist and independent researcher,[1] I find myself in emphatic and absolute agreement with such interventions. These signal the possibilities of anthropological engagement in rich, nuanced, and meaningful ways—ways that we often take for granted, or which may be considered expendable in the political economy of academia and professional work.

I write this essay with a view to expand the conversation about abuse, precarity, and ethics outside of our disciplinary boundaries; to ground this discussion in a field where its consequences can be discerned, contemplated, and acted upon. So, while there are potentials that our insights from the Hau debacle inform how we practice our discipline in spaces of disciplinary reproduction (e.g. through journals, classroom teaching, or the blogosphere), I want to ask: How can we take these very insights to the spaces where we practice our craft to make a living? How do we transform them into a genuine “never again!” commitment?

How do we use the Hau controversy, and our collective learnings from it, to further pedagogic and professional conversations about sexual harassment, workspace abuse, and the ethics and politics of producing knowledge?

Towards a triad of ethical principles

Ethical dilemmas about the nature and methods of knowledge production—and of “putting it to use”—are seemingly woven into the very fabric of anthropological endeavours. Our discipline’s complicity in colonialism, the persistent coloniality of knowledge, the silencing of anthropologists who are black, indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC), aren’t simply issues in the discipline, but have a deep bearing on our collective professional identities. Added to this, of course, are the continuing efforts to make our discipline accountable to the people we work with and study.

The ethical debates of the 1970s and 1980s are a good point to start, since they put to the fore the very political nature of anthropological knowledge and practice.

In a significant way, these debates were about the changing nature of anthropological practice as it was moving outside the academe into the “professional” world of government and corporate services. This, Gerald Berreman (2007: 308) warned, could be a “license for unfettered free-enterprise research.” As a staunch opponent to the use of social sciences in US military interventions, Berreman argued that anthropology and anthropologists, whether in academia or professional settings, should adhere to a unified set of ethical principles: responsibility to those being studied; avoiding clandestine or secret research; accountability towards the scholarly community; and, bearing positive responsibilities to society at large.[2]

Berreman’s concerns about unethical anthropological work are well-founded, since ethics derived from scholarly practice can be at odds with professional practice, the latter being often driven by profit motives which reduce liabilities for employers. He believed that it was possible—if not desirable—for anthropologists to be “humane students and advocates of humankind,” because there was “no place anywhere for unprincipled anthropology or anthropologists” (314).

Peter Pels (2000: 140, 145), on the other hand, is much less polemical than Berreman and more attentive to the ambivalence and relative weakness in anthropological ethics which, he points, is paradoxically accountable to the interests of sponsors as well as research subjects. A part of this weakness is that the code of ethics essentially depoliticizes anthropological practice, since the bearer of ethical responsibility is an isolated individual practitioner. To counter this, Pels argues, we need more “emergent ethics” which places politics back inside, historicizes methodology, and takes the anthropologist as a “relational subject,” whose practice is located in the negotiation of individual and communal interests (162-163).

It is no coincidence that feminist ethnography and practice have offered more cogent and relevant responses to this dilemma.

As Elizabeth Enslin (1994: 539) argues, feminist ethnography and research draw from a rich genealogy of political struggles grounded in the material conditions of women, and has continually aspired to—and been successful in—disrupting the dichotomy between “theory and practice,” “academia and activism.” Enslin attempts to move beyond conventions of “writing” or textual strategies as outcomes of engaged research by focusing on praxis. She argues that our mode of doing research and presenting our research findings in written forms may radically change if we are more attuned to dynamics of political accountability, and if this informs the choices we make about what we study, and where we study it (558).

In this way, writing can be a way of furthering our engagements—one option among many viable/visible forms of engagements—not all of which are valued in the political economy of academia, but become indispensable in our practice and conduct with our collaborators, participants, and subjects (559).[3]

From this very brief review I can offer the following triad which can chart out and explain how ethical principles can potentially be developed and practiced in a unified way. Such an ethical framework includes:

[a] Principled and humane commitments to do no harm and strive to do good, which are [b] Orientated towards politics and power relations, rather than neutrality, and are the basis of [c] Developing and refining methods of research, communication, and multimodal engagements with different stakeholders, which are based on care, reciprocity, and critique, and applied within and beyond disciplinary boundaries.

Now, let us try to sketch what this triad would look like in different fields of engagement outside disciplinary practice.

Partial notes, provisional practices: Two dilemmas

My interventions certainly do not encompass a wide range of professional anthropological practice; instead, I limit it to contexts that I know best, such as public health, development, and non-profit work. These sectors also involve working with vulnerable and marginalised communities, thus making the need for ethical discussions quite relevant. The first dilemma, then, is about negotiating professional engagements as a part of engendering ethical responsibility; and the second, deriving from the Hau issue and the Me Too movement, is how we may ethically intervene in instances of sexual harassment and abuse in workspaces.

With regard to the first, as many other practicing anthropologists know well, employers, administrators or colleagues are often unaware of the background and history of anthropological epistemology and methods, and look to us as generic “qualitative” researchers. This constrains the depth and open-ended nature of our professional engagements through pre-defined mandates, shorter timelines, and the demand for (quantitative) evidence.

This characterises much interdisciplinary work in the outcome-oriented political economy. Ethics, insofar as they are required, are quite formalised, usually obtained through bureaucratic structures like government or medical communities. They function more to reduce liabilities for organisations and their clients, rather than being directly accountable to the communities or people they might engage with.

Berreman’s concerns are thus quite valid here, since such imperatives may indeed fuel laissez-faire research, which abandon principles for certainty and speed. But, if our work must be informed by the principles outlined in the triad above—and, like Berreman, I insist that they must—then what we need is a way to combine legitimacy and legibility.[4]

So, how can the triad be of use here? Both [a] and [b] are, for practical reasons, difficult to achieve—and even if they are, they are rendered invisible in the final outcomes of our work. But [c], on the other hand, is inherently attuned to “what we do” and “how we do it”—and actually informed by [a] and [b].

One way, then, would be to explicitly draw attention to how inequalities and marginalisation are also ethical problems that researchers must deal with, which have direct bearings on the nature and utility of the knowledge produced.

During my fieldwork, for instance, one of my colleagues/collaborators said that many NGOs increasingly employ the “bhasha” (language) of “projects,” rather than that of “andolan” (social movements) (Chakraborty 2016). While his statement is certainly a critique of depoliticization of NGO work under neoliberal regimes (Bernal & Grewal 2014), I believe that it also points to a novel way of “using” such a “language of projects,” utilising ethnographic methods to translate critical insights into hitherto apolitical actionable agenda items that adhere to the values of social movements.

Here, we must seek to become very different sorts of “insiders” in institutional and organisational networks (Riles 2002), working ethnographically, bureaucratically, as well as in activist modes—producing fieldnotes, ethnographies, as well as manuals, protocols, drafts, and other materials within a unified ethically-informed framework. As both Pels and Enslin rightly point out, much of this remains either invisible or unwritten; thus, it is in our best interests to centre such efforts in new, innovative ways (see, Hale 2006; Osterweil 2013).

Now, let us discuss the second dilemma: the issue of harassment and abuse in workspaces. Admittedly, much of this conversation is inspired by the Me Too movement; but neither does that alone mean it is easier to have the conversation, nor is it enough.

Feminist anthropologists, gender-based violence (GBV) scholars, and activists have long been aware of the rampant, structural nature of sexual abuse and violence.

It thus was necessary for scholarship and activism to be unified from the beginning to attend to survivors’ needs and welfare and reflect realities of power. This is true for domestic violence and abuse, as well as workspace abuse and sexual harassment, where the latter are also experienced more acutely by black, indigenous and women of colour, and gender non-conforming and trans individuals. Both forms of abuse are about the concentration and exercise of (male, white, patriarchal) power, and are directly linked with the political economy of work and labour—informalisation, precariousness, wage gap, and so forth.

This makes it quite difficult to apply any form of ethics, where the need for, and function of, them are quite different. Many formal ethical guidelines certainly are needed, and many exist in the form of human resource guidelines, fieldwork guidelines, or laws as a result of sustained feminist activism (e.g., the Vishaka Guidelines against workplace sexual harassment in India, or Monash University’s Guidelines for Responding to Allegations of Sexual Offence). But as decades of feminist practice has taught us, at times these are insufficient, are sources of violence themselves, or fetishised as “due process” without any structural change.

We are confronted here with an issue that is admittedly vexing, and any interventions that anthropologically-informed principles or ethics can make are somewhat limited, since they might be complicit in such structures of violence.

But if the responses to the Hau controversy are any indication, the possibilities are there.

For one, our sensitivities perhaps need to be modelled after the historical labour of front-line workers who have worked towards caring for and supporting survivors of violence and abuse (Wies & Haldane 2011). Echoing Mathur’s critique of “our reluctance…to be ethnographic enough when it comes to our own quotidian and institutionalised practices,” this means we extend our professional, scientific, and principled sensitivities to these “whisper networks” with the explicit aim of taking the “evidence” seriously—the [b] of the triad, i.e., “be political, not neutral.” In many situations, there are also no other options than to insert ourselves into spaces where our presence and ethical principles—the [a] of the triad, i.e., “strive to do good”—can have positive outcomes for survivors, whether it be through women’s or grievance redressal cells, or HR committees.

This means that our engagements with this dilemma must, essentially and necessarily, move beyond our academic or professional roles, but require the existence of anthropology’s conceptual vocabulary of engaging with “others.”[5]

Following Haldane (2017: 6-7), the [c] of the triad requires the practice of “interpretive labour”—an imaginative identification with an “Other,” that also sympathises with them (Graeber 2012).[6] In performing this interpretive labour, as principled anthropologists, we need “to understand [survivors], to feel compassion for their struggle, and to make sense of what their needs are.” However, this does not mean that we become caregivers ourselves, which would be both naïve and dangerous.

Our training does attune us to empathy, but that is not a substitute for professional therapeutic or psycho-social care that survivors may require (indeed, doing so might cause harm to them; it is our responsibility that we strive to find out what structures of care exist, and ensure these are accessible to them).[7]

The triad of ethics sketched above isn’t a terribly original idea, nor are the two dilemmas where I’ve applied them exhaustive of the ethical quandaries that confront us. But they are a step in the direction of articulating things that have been left unsaid in our discipline—Mathur’s “shocked, not surprised”—when it comes to our ethical conduct beyond and within our disciplinary boundaries, or lack thereof.

Perhaps what we need in such times aren’t revolutionary resuscitations of old, white and male anthropology, but the persisting labour of our peers, participants, and other activists who are attuned to, and practice their politics in radical but quotidian, principled ways.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Ned Dostaler and Aakash Solanki for helping shape this conversation early on. I’m deeply thankful to Hillary Haldane for her encouraging comments on the earlier draft, and to Julie Billaud for her editorial guidance. I’d like to thank David Osrin, Nayreen Daruwalla, and my other colleagues, collaborators and research participants in Mumbai for their continued inspirational work in preventing violence, and their struggles to build better, more equitable worlds.

[1] Disclaimer: My recent and ongoing professional engagements are with an NGO that involves women front-line workers in their violence prevention intervention in various urban poor neighbourhoods in Mumbai, India. I am currently associated with them as a research consultant, and my work profile includes using ethnographic methods to conduct formative and evaluative research, as well as producing deliverables, and providing training to field staff. I thus describe myself as both an applied and practicing anthropologist. All views expressed in this essay are my own, and do not represent the beliefs or values of my colleagues or collaborators.

[2] These were a part of the Principles of Professional Responsibility (1971) before they were deleted in the 1984 draft of the Code of Ethics.

[3] Intersectionality is an indispensable part of this configuration, and I regret not being able to make a more in-depth analysis of how feminism, critical race studies, indigenous activism, queer activism and theory, and other counter-hegemonic modes of knowledge production and social action can—and have—made rich, lasting contributions to sort of ethical praxis and principles I hope to elucidate in this essay. Further, as Hillary Haldane pointed to in a comment, Ruth Behar and Deborah Gordon’s Women Writing Culture was an explicit challenge to the male-centric Writing Culture.

[4] I would like to thank Aakash Solanki for a short, but insightful conversation we had on these issues. I’d also like to point that alternatives are both available and possible, as much of my experience with front-line workers has shown. Many organisations do find utility in ethnographic methods, and it is incumbent upon anthropologists, both of the academic and practicing varieties, to harness the potentials.

[5] While I write with the collective pronoun “we” or “us” referring to those in the anthropological community, a necessary caveat is in order: it is especially incumbent upon those of us who enjoy the relative privileges of being white, male, cisgendered, and/or upper class/caste that we pay special attention to such ethical conduct. Unless we check our privileges, our claims to principles are insufficient and worthless.

[6] Although Graeber has coined the concept in the context of structural violence and bureaucratic work, it is quite ironical that he was unaware of its gendered connotations before writing the essay, and more so that his Guardian essay post-Me Too was focused solely on his mother’s experience of abuse, rather than the historical and structural nature of violence against women, even within our discipline. Once again, I have Hillary Haldane to thank for our discussions on this issue.

[7] This is a lesson that I have learnt the hard way in my work with survivors of domestic violence. As a colleague of mine said, half measures are dangerous, and avoiding them is at times the most ethical thing to do to prevent harm.

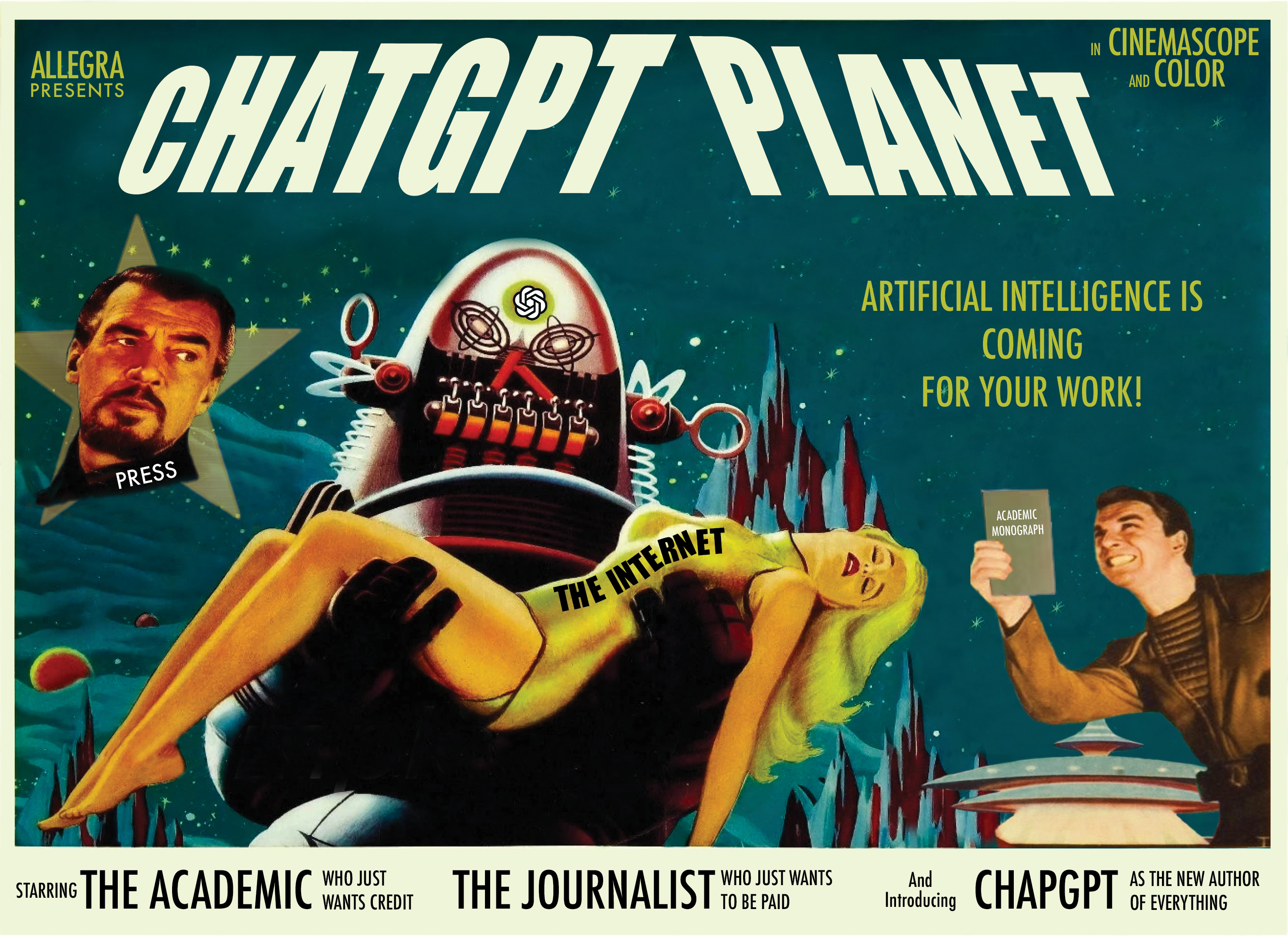

Featured image by Akshay Paatil on Unsplash