Hundreds of thousands of migrants from the Horn of Africa have systematically crossed international borders throughout Africa into Europe in the last decade. Among them were over 150,000 Eritreans fleeing the lack of freedom and poverty in their country. In order to reach Europe, many of them had to cross at least three international borders undetected: from Eritrea to Ethiopia or Sudan; from Sudan onto Libya; and finally from Libya into Italy.

However, these borders are not easy to cross for those – refugees, in the first place – who have almost no possibility to obtain a legal visa, due to their typical lack of passports and the impossibility to provide any guarantee of return upon the expiry date of their visa. Refugees have to travel through impervious paths where they are less likely to be discovered by authorities. As they usually lack the knowledge and the means to cross these borders by themselves, they have to pay professionals who can enable them to do so.

These professionals are usually depicted as cruel exploiters in the public debate, but my fieldwork with Eritrean refugees in Sudan and Ethiopia en route to Europe points in a different direction.

First of all, it is important to consider that the word ‘smuggler’ in the Eritrean context includes a wide variety of professionals with very different responsibilities: there are guides, who accompany migrants across the borders on walk; drivers who take them by car; middlemen who put guides and drivers in contact with customers. Middlemen can do business in more or less professional ways. Some may occasionally connect customers with drivers and guides in order to receive a cut of the total price. Others work more systematically and turn the role of middleman into their main source of income. Middlemen can arrange different parts of the journey based on their contacts, or different kinds of services, such as the provision of fake documents and marriages of convenience.

During my fieldwork, I met two professional middlemen who were operating on the route from Eritrea to Libya. They were Eritrean refugees themselves. One of them, Tesfay, an ex-military man in his late twenties, had started the business after few years spent in a refugee camp in Northern Ethiopia. The other, 23-year-old Michael, had been in the smuggling business even before escaping Eritrea. Indeed, he told me that he had spent several years in the worst Eritrean prisons because of it. To me they were both kind and friendly: they believed that by talking to me they were helping inform the world of what their people had to go through in order to escape the lack of prospects and freedom in Eritrea.

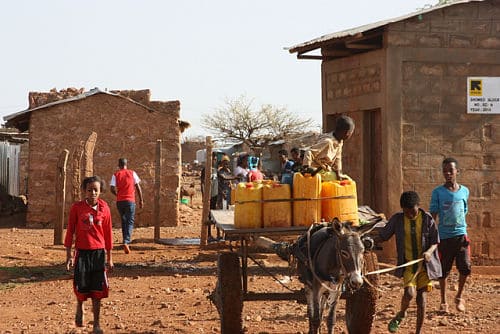

Photo by EU/ECHO/Malini Morzaria (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In contrast to common images of ‘smugglers’, Tesfay and Michael were well-integrated in their national communities in exile. Tesfay regularly frequented church and contributed to its activities. Alongside his workmates, Michael used to spend time with a large group of Eritrean families and friends he had known since his childhood in Eritrea. He was generous to them and was manifestly loved by them. Although both Michael and Tesfay tended to keep their business separate from their interactions with their closest friends and family, they did not seem to be too secretive about it or to be ashamed of it.

Asked how he felt about his own business, Tesfay replied with an interesting metaphor:

“You know, in life good things go together with bad things. Even a doctor has to do things that imply a high risk and sometimes the death of his patients. For example, when a doctor takes his patient into a surgery room, he has to ponder the possible risks and positive outcomes of the operation. Similarly I have chosen to look at the positive outcomes of my work: if my customers go through the surgery [and it is successful] they will have huge advantages.”

Unlike mainstream narratives, Tesfay did not consider his job as contributing to worsening the situation of his people. Rather it was a “remedy”. He was just providing the means to quench people’s thirst of a better life and freedom of movement.

Among refugees, middlemen were not judged negatively unless their services had proven to be untrustworthy. Gerre, one of my informants in Khartoum, once commented about a middleman we had just met: “He is an honest one, all the people he sends are getting safe to their destination”. Other Eritrean informants in Italy relayed that they were still morally indebted to those middlemen who enabled their safe passage to Europe. Certainly, during my fieldwork I also collected several accounts of dishonest, inhuman smugglers, who cheated their customers or even sold them to traffickers known for torturing refugees in order to extort ransoms in the thousands of dollars from their families abroad. However, smuggling was not a despicable activity in itself according to my informants, but could become extremely condemnable in some circumstances.

A middleman should be trustworthy.

Customers and middlemen alike said this to me repeatedly, the latter especially stressing this several times during our time together. “I take responsibility for the people I send”, Tsegay told me once with pride. Likewise Michael stated on another occasion: “I care for my customers….do you remember the other day when I told you that I was busy? It was because a truck of people from Ethiopia had been caught by the Ethiopian police. I paid money from my own pocket to free them!” Tsegay’s and Michael’s caring attitude towards their customers and their claim of “being responsible for them” can be interpreted as part of their ethical code or an expression of empathy for the groups of refugees they smuggled, but it was also as a marketing strategy. In fact, they both knew that their business depended on their reputation as honest and reliable middlemen, who were able to make refugees’ dreams of mobility come true.

In the current asylum scenario, those refugees who manage to flee their countries are mainly destined to long-term encampment in the first safe country. This is due to the fact that local integration there is often not allowed or limited, conflicts back home are often long-term, and resettlement to third countries concerns a minimum percentage of vulnerable refugees (something between 1% and 2% refugees worldwide). In this context, professionals of irregular migration represent one of the few chances refugees have to move out of camps and reach a place where they will not only be safe, but also able to access a decent life. From this perspective, it is not hard to see that even cruel smugglers can turn into heroes and that refugees may not judge these individuals as negatively as the public European debate does.

Our co-producer openDemocracy offers more food for thought on human smuggling:

- Beyond common-sense notions of human smuggling in the Americas, by SOLEDAD ÁLVAREZ-VELASCO and MARTHA RUIZ

- Smuggling as social negotiation: pathways of Central American migrants in Mexico, by YAATSIL GUEVARA GONZÁLEZ

- The call to become a smuggler, by LUIGI ACHILLI

- Precarious livelihoods in eastern Indonesia: of fishermen and people smugglers, by

- Governing migrant smuggling: a criminality approach is not sufficient, by ANNA TRIANDAFYLLIDOU

- The struggle of mobility: organising high-risk migration from the Horn of Africa, by TEKALIGN AYALEW MENGISTE

- Communities of smugglers and the smuggled, by NASSIM MAJIDI