The decision of people in Britain to leave the European Union has come as a surprise, even a shock to most of my friends and colleagues who work in academia here in England. While the EU’s neoliberal tendencies and never-ending crises in banking, sovereign debt and migration made the deficiencies of the organisation clearly evident over the past years, most of us had not expected that a majority of people in England and Wales would consider a drift back into nationalism to be the appropriate response. Sure, it is not usually our job to deal in short-term predictions of social trends, and anthropologists have famously missed the rise of important political currents in the past. [1] But to many of us, the extent to which we have misread the mood of people in large parts of Britain today feels highly unsettling.

This surprise is partially grounded in the fact that the economic case for leaving the EU was unconvincing. Economic analysts inside and outside of Britain had made clear that the net weekly savings of £350m promised by the leave campaign were a myth, that abandoning the EU was likely to cost Britain far more than its actual weekly contributions, and that the British economy substantially increased its risk of recession as a result of Brexit. Michael Gove, the Conservative Justice Secretary and a key figure in the leave campaign famously countered these arguments by declaring that the people of Britain “have had enough of experts […] saying that they know what is best and getting it consistently wrong.” Today, it seems, that voters in the referendum may have tired of economic reasoning altogether. The leave vote turned out to be strongest in those parts of the country that are most economically dependent on the EU.

Now that the votes have been cast, teleological accounts as to why the referendum turned out as it did abound, and at this point it seems too early to provide an authoritative summary of what has happened. As usual, political commentators on the right and on the left highlight predominantly economic reasons for the vote, pointing to the fact that people in the most deprived parts of England and Wales were the ones who wanted Britain out. After decades of seeing their public services reduced to shambles and their job opportunities nullified, it is likely that they wanted to show the politicians in both Brussels and Westminster that they had nothing left to lose. A clear case it seems, of popular disregard for bureaucratic elites, and maybe even a revolution by the people, in an act of popular democracy.

While this account seems plausible at first, we should be reluctant to accept it as the whole story. Generally speaking, economistic reasoning can never explain why people respond to their social predicament in the way they do. As E.P. Thompson (1967) shows with reference to food riots in 18th century England, people living in poverty do not react to economic stimuli in a spasmodic fashion. [2] They are just as likely to retreat from party politics, to resort to political activity other than voting, or they may hold on to the belief that abstract institutions represent their interests, even when that is not the case. The links between deprivation and a protest vote are not hard and fast, and we need more precise explanations of why economic circumstances led to the very specific political outcome that we now face. After all, the notion that people chose the contrived opposition between Britain and the EU in the first place makes little intuitive sense [3], and their decision to vote leave might have to be understood in a cultural context in which economic hand-outs are equated to a lack of autonomy and dignity.

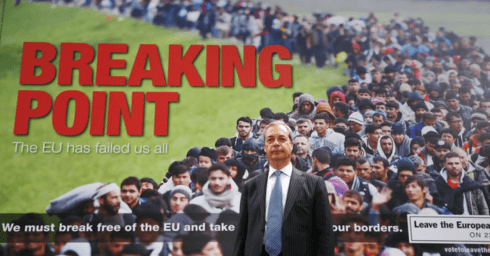

Moreover, we should acknowledge that the EU referendum has been orchestrated by political elites from the start. Far from being a natural result of widespread economic inequality, this political process was instigated by the Prime Minister David Cameron to ensure the continuous support of Conservative party members. His equally privileged rival Boris Johnson pushed the economic case for saving EU membership fees and fuelled anti-bureaucratic sentiments against Brussels, while former commodities trader, lobbyist and right-wing figurehead Nigel Farage successfully equated Britain’s EU membership with a lack of control over immigration. Their attempts at heightening and using “integralist” sentiments of romantic collective belonging, cultural difference and alienation from modern society [4] failed in Scotland and large parts of Northern Ireland. In England and Wales, however, the absence of a strong opposition allowed their triumvirate of political incompetence, an empty will to power and anti-intellectualist xenophobia to win the popular vote. It turned what could have been a measured re-assessment of political allegiances into yet another exercise in escalating tensions along national and religious lines within Europe [5]. So while the referendum has surely been shaped by economic inequality and deprivation, it has also been an illustration of right-wing elites capturing the public discourse so as to to steer public grievances toward ethnic and racial “others” – and away from their own austerity policies.

This is where the humanities and social sciences come in. The current rise of ethnic, racial and religious prejudice throughout Europe – and the United States for that matter – are a call for action to us as academics. We have not been outspoken enough on these topics over the past few years, and should respond to Brexit by consciously renewing our engagement with the public. If we refuse to do so, we risk repeating the mistakes of conservative and liberal intellectuals in 1930s Germany, who all too often responded to the rise of xenophobic populism by means of “inner emigration”, i.e. the retreat into spaces of like-minded interlocutors.[6] Put off by what they considered the aesthetic sensibilities and argumentative incoherence of the populists, these potentially critical voices chose not to engage a broader audience. It may be tempting to behave like this again today, but Britain’s decision to leave the EU so as to control immigration, and the recent killing of British MP Jo Cox in the run-up to the referendum, are clear calls for our greater involvement in public discourse. If we ignore the rise of popular xenophobic sentiment it may have dire consequences in the long run.

Anthropology is particularly well-equipped as a discipline to challenge the current tides of national, racial and religious prejudice, before it is too late. We have long thought about many of the key terms that shape European politics today, such as “culture”, “identity”, “nation” or “tradition”, and we tend to deal in nuance, which is a quality that is sorely lacking in contemporary public debates around immigration and sovereignty. While we should certainly continue our academic work to the best of our abilities, we also have a responsibility to engage our work with multiple publics, to unsettle and challenge the accounts of the political elites fostering xenophobia and anti-intellectualism [7]. Before the EU became synonymous with violent austerity politics in the Mediterranean, it was one of the key institutional structures that successfully worked to overcome national and ethnic conflict in Europe. Maybe it is not the best such structure to continue this work today, but the goal remains important, and as anthropologists we have a lot to contribute to the broader socio-political project of bringing about a climate of tolerance and peace.

[1] Starn, O. (1991). “Missing the Revolution: Anthropologists and the War in Peru.” Cultural Anthropology 6(1): 63-91. [2] Thompson, E. P. (1967). “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism.” Past and Present 38: 56-97. [3] Hann, C. (2016). Awkward Island (a Welsh-Eurasian Perspective on “Brexit”) [accessed 26/06/2016]. [4] Holmes, D. R. (2000). Integral Europe: Fast-Capitalism, Multiculturalism, Neofascism. Princeton, University Press. [5] Eriksen, T. H. (2016). Europe’s Destructive Spirals of Distrust. Sapiens. Online. [6] Benz, W. (2003). “Widerstand traditioneller Eliten [Resistance of traditional elites].” Informationen zur politischen Bildung Deutscher Widerstand 1933-194 [German resistance 1933-1945] 243 [accessed 25/10306/12016]. [7] Compare Eriksen, T.H. & Felix Stein, (forthcoming) ‘Anthropology as counter-culture’ – An Interview with Thomas Hylland Eriksen, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

This post was originally published on PoLAR blog.

Featured image by frankieleon (flickr, CC BY 2.0)