Researching with social movements (environmental activism, makerspaces) brings ethnography’s nuanced, embodied and collective sense-making to the fore. I also argue that anthropological research within academia is important in its own right.

I have always been puzzled by the vastly different ways people relate to environmental change. Why, I wonder, do other people not fear the same things I do?

As a graduate student at the start of the 1990s, this puzzlement led me to pursue anthropology in what was then an unusual place. My peers in the early stages of their PhDs headed mostly for far-away or socially marginal places, but I put my bicycle on a ferry destined for a European town that I had selected for its ordinariness. Its main draw was that it had an active population of environmental activists. Looked at another way, I had chosen to study a place where literal environmental changes could be visible. Some, but not all, of the city’s denizens had begun to try to take action to prevent further environmental damage.

I was acutely aware that I was very much like them. In fact, I knew that I wanted to learn from them as well as about them. How does one campaign against toxic waste transports or motorways? How can scientific findings be used in environmental protest? How do activists keep going when they are dismissed as utopians?

Here I reflect on how these early experiences brought me to this exciting conversation as part of #colleex about experimental ethnography. It has never been my explicit intention to use or develop experimentation as a way to understand emergent social issues. Nevertheless, my professed sympathies for the various activists I have worked with and written about appear to have put me into situations where my sense-making and their sense-making are so mutually entangled, that some word of warning about my approach – perhaps “experimental” – has often felt appropriate.

Working increasingly with design researchers for whom interventionist methods are old hat, I have also started to think about experiments that might serve serious intellectual as well as political purposes.

Thus, with my friend Hanna Kaisa Vainio we did a community art project[1] walking and sharing stories about changing urban landscapes in Helsinki, seeking more convivial ways than usual for articulating feelings about environmental change. We produced a one-off zine or fictional newspaper, Skutsi Huutaa (Call of the Forest). For many who participated, the whole process was more rewarding and significant than we had expected. We are now looking at developing urban walks explicitly using the terminology of experimental ethnography.

Background – living in unnerving times

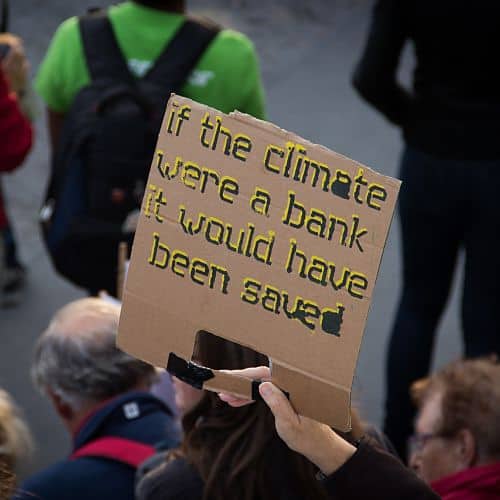

My research has focused in recent years on self-organising urban activists in Helsinki, particularly groups spurred on by global environmental concerns. Working with environmentalists I often feel they are totally justified when they describe ours as “the age of stupid” but it could equally be the “unimaginative age”. Even many people who profess to be green find it impossible to imagine a world beyond accumulation and individualism. At the same time, it’s interesting how many activists appear delighted by my disciplinary background.

They would like to find anthropological evidence that life could be organised differently.[2]

Certainly we need to open up the space of politics and imagination while also respecting what we know through technoscientific means about what dangers human society is facing. The problem is not new. For instance Marilyn Strathern and Donna Haraway spelled it out well thirty years ago. They sought ways of holding onto “an account of radical historical contingency for all claims to knowledge” and maintaining “a (proportionate) commitment to truthful, faithful accounts of the world” (Strathern 1991: 31).

Yet reductionism pervades collective decision-making. Political subjects are expected to be clear about “whose side” they are on.

Scholars are of course taking note and even pushing their own work closer to more journalistic rhythms, engaging more deeply and effectively in social life. Since 2011, the journal Cultural Anthropology has offered space for scholars to comment with an urgency not usual in academic life. A recent example, in a series on ‘Trumpism’, was Michael J. Fischer’s call for forms of counter play “that can move people toward dialogic platforms and organizational networks” even in the apparently post-truth environment where slogan words and other simplifications “‘magically’ divide friends from enemies”.

Anthropologists have picked up on this problem and combined experience-near ethnographic knowledge with analysis of large-scale pressures on social life. In Fischer’s words, “Anthropologists have the ethnographic skills and community connections in places they have studied to give journalists and historians and other social scientists, the on-the ground access that make statistics, mapping, modeling, and other techniques have bite (or be shown up as mirages), rather than just satisfying statistical measures and margins of error in abstract models” (Fischer 2016).

There are many others also, particularly in design, for whom ethnography is a key to addressing world-wide problems. This work shows that ethnography can be done well anywhere (Light 2015) and most anthropologists have fortunately let go of the old view that ours is the only discipline that can make sophisticated use of ethnography. If efforts to make sense of life (a not unreasonable gloss on ethnographic research, I think) are intensifying everywhere, ethnographic methods are bound to appeal.

I have myself become more confident with the value of my own adventures in ethnography. This is despite the knowledge that their results are meagre compared to the avalanches of information and reportage emanating from higher-impact research outlets, think-tanks and corporate research ventures. Increasingly though, “human stories” are valued, and there is a greater recognition that they “are not the opposite of data” (Quagiotto 2017). However, the stories anthropologists share are overwhelmingly sombre. The discipline can even be characterised as specializing in the darker and sadder implications of recent planetary history (Ortner 2016).

Even in my work, always carried out in lucky places – middle-class Germany, England and Finland – the anthropological stories I have drawn out through ethnographic encounters have frequently concerned processes and conditions that embarrass or upset “polite society”.

Since 2010, I have participated in various Helsinki groups working towards a more liveable future environment. Unsurprisingly, one of the most rewarding as well as academically productive parts of this has been an urban garden. Getting my hands into the dirt there satisfies what feels like a physical need. Solving and creating problems together with activists keeps our spirit alive. Exchanging ideas and making plans and organising events, doesn’t just push our thinking. I believe it generates a form of collective imagining (Gatens and Lloyd 1999) that seems as necessary for my friends there as it is for me.

Ethnography as learning together

This corporeal vocabulary points to a key feature of all ethnographic research: The researcher’s body-mind is the most important tool of research. At the same time, the insights generated only exist in the overlapping spaces occupied by collective body-minds. To wit, if my experience of ethnography has been that it is a process of learning together, it is also an embodied one.

Recently together with my colleague Cindy Kohtala, a design researcher who has done ethnographic work in several makerspaces more or less explicitly seeking to contribute to sustainability transitions, we have been playing around with the idea of ethnography as a form of collective but productive confusion.

Doing and thinking together is how humans learn. And that is core to what all ethnographers do, in design and in anthropology.

The argument we are developing explores how activists in makerspaces almost relish the confusion and lack of rigour that reigns in their activist life. Self-consciously tolerating the confusion that permeates their shared experiences is what allows them to generate material things, knowledge and above all new questions. Among the literature that inspired us were methodological reflections by anthropologists (Corsín Jiménez and Estalella 2016, Smith et al. 2016) on how to attend to marginalised forms of materiality, experience and knowledge. At the same time we were aware of how ethnography as part of design is a professional practice that has cultivated probing and experimental practices in a distinct set of conversations that sometimes cross with the critical anthropologists’ interventions.

In fact, the hallmark of experimental ethnography for me is that it combines nuanced descriptions of how things are with constructive ways to probe the way things might be.

Perhaps even more intriguing, and more existentially rewarding, is the way this kind of work highlights and spells out the shared intellectual yet also embodied as well as morally laden work of opening up the “black boxes” of the modern heritage (Corsín Jiménez and Estalella 2016, also Fortun 2014). Here working alongside, with or even sometimes as an activist, the task appears as one of making the world or the environment something one can learn.

Borrowing from Corsín Jiménez and Estalella, ethnography shades into a series of exercises in learning autonomously but not in isolation.

This does, however, provoke anxiety concerning the authority of our ethnographic efforts. Anthropologists working among professionals (Holmes and Marcus 2010) have long had to negotiate their way out of the anxieties and uncertainties that have come from producing knowledge alongside sophisticated and respected experts in their own fields.

Those of us who work with social movements are luckier I suspect. For activists are always social analysts in their own right. Working with social movements as academics amounts to a dream situation of being with highly reflexive interlocutors who are themselves often experimenting with how to talk and to listen and who are highly aware of being caught up in distortions imposed by power (Jasper 2016: xvii.)[3]

Ethnography out of academia

A scholar of the political life needs, in some way, to go native. Whatever the epistemological framework, as I discovered during my first fieldwork with highly qualified German environmentalists (Berglund 1998) scholars and activists do similar things (Osterweil 2013, Jasper 2016). I also suggested above, that normalizing ethnography as a mode of knowledge production has gone hand in hand with the growth of design’ social role. We can all be ethnographers now!

I worry, nevertheless, that significant distinctions among knowledge practices can get lost here. Cindy’s ethnography as well as mine generate a particular kind of value because they put activist sense-making together with academic reflection. Juxtaposing activist with academic concerns undeniably produces overlaps. But it also prompts us to attend to particular details and ask questions that relate to discourses quite – or at least partially – separate from our fieldsites. I think we need to protect that difference.

More broadly, there are intellectual virtues within the academy that must be defended (Brown 2015). In relation to expertise and its social power – or lack of it – Kim Fortun (2014: 312) points to a related practical issue of some urgency : we may never have been modern, but we have a modernist mess on our hands. The dynamics of the complex networks of networks on which people’s lives now depend will never yield themselves to activist or stakeholder “learning”. What we need is dedicated, painstaking research that makes things visible that have been black-boxed either on purpose or through inattention. We need dedicated spaces for experimentation, not just of the ethnographic kind.

The point about academia is it takes nothing for granted.

But it needs a strong institutional foundation and more or less disciplined knowledge practices to refuse to take things for granted. To live with climate change we will need palaeontologists who can help abstract out what the stakes are. To cope with endocrine disrupting chemicals and the tragedies that come with them, we will need scientists as well as the detached science that their endeavours produce.

In anthropology, perhaps we need to carry on as we have recently, drawing attention to the sad things that those in power overlook even when they themselves are the cause. As Ortner (2016) argues, specifically anthropological reflection on colonialism creates exceptionally fertile ground for analysing how the conditions of life for most people and places are shaped.

What’s interesting about my experience of activism, from 1990s science-based campaigns to today’s guerrilla urbanists, is how it has become aligned both with this appreciation of the costs of modernity-as-usual and the quasi-ethnographic collective confusion of social movement work. In other words, experiments don’t need to be produced by professional ethnographers or anthropologists, they are taking place anyway. Perhaps we have, as many have noted, no option but to be experimental (Julier and Leerberg 2014).

But even if that is the case, not everything need be left to accidental individual trajectories like mine.

It’s time for (even more) anthropologically informed experimental ethnography.

Thanks to Adolfo Estalella and Cindy Kohtala for their helpful comments.

References:

Berglund E K 1998 Knowing Nature, Knowing Science: An ethnography of local environmental activism.

Brown W 2015 Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution.

Corsín Jiménez A and A Estalella 2016. ‘Ethnography: A Prototype’, Ethnos, pp. 1-21. DOI: 10.1080/00141844.2015.1133688

Edelman M 2001 ‘Social Movements: Changing Paradigms and Forms of Politics’ Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 30:285–317.

Fischer M J 2017 “First Responses: A To-Do List.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology website, January 18, 2017.

Fortun K 2014 ‘From Latour to late industrialism’. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4(1): 309-329.

Gatens M and G Lloyd 1999 Collective Imaginings: Spinoza, past and present.

Holmes D R & G E Marcus 2010 ‘Epilogue 2: Re-functioned ethnography’, in M Melhus, J Mitchell, H Wulff (eds) Ethnographic Practice in the Present.

Jasper J M 2016 ‘Foreword’ in Fillieule O and G Accornero (eds) Social Movement Studies in Europe: the state of the art, xiv-xviii.

Julier G and M Leerberg 2014 ‘Kolding – We Design For Life: embedding a new design culture into urban regeneration’, Yhdyskuntasuunnittelu / Finnish Journal of Urban Studies, pp.39-56. Also online.

Light A 2015 ‘Troubling futures: can participatory design research provide a generative anthropology for the 21st century?’ Interaction Design and Architecture(s), 26. pp. 81-94.

Ortner S B 2016 ‘Dark anthropology and its others: Theory since the Eighties’, HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 6 (1): 47-73.

Osterweil M 2013 ‘Rethinking public anthropology through epistemic politics and theoretical practice’, Cultural Anthropology, 8(4): 598-620.

Quaggiotto G (2017) ‘Big data meets thick data’, BOND website ‘Development predictions for 2017’.

Smith R C, K T Vangkilde, M G Kjaersgaard, T Otto, J Halse, T Biinder (eds) 2016 Design Anthropological Futures.

Strathern M 1991 Partial connections.

[1] Finnish language website at https://narratiimi.wordpress.com/

[2] A similar tendency featured in anti-growth protest in the 1960s and 1970s.

[3] This only applies, however, to social movements that we as anthropologists sympathize with (see Edelman 2001).