Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle (Saale) / Germany

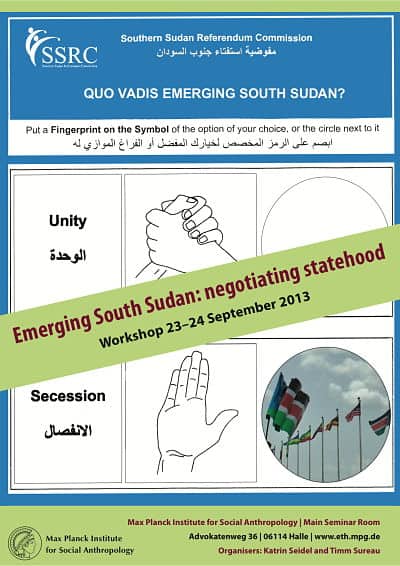

September 23rd – 24th 2013, Organisers: Katrin Seidel, Timm Sureau

Recent analyses of the situation in emerging South Sudan are often based on short-term research and on external sources and policy-driven assumptions. By following an underlying Weberian concept of statehood, current studies often draw -uncritically- on rather ‘classical’ constitutive elements of statehood, such as territory, sovereignty and an efficient bureaucratic system. The state is assumed as an a priori conceptual object. This reductionist approach has consequences for the analysis of statehood.

It “obscure[s] an otherwise perceptible feature of institutionalized political power, the state-system” (Abrams 1988, 79). It concentrates on assumed state functions and less on the people’s perspectives on the state, thereby neglecting an important part of state formation: the inner perspective. The realities of emerging South Sudan show that the concept of ‘state’ as such is not (yet) completely accepted by the people. Therefore, a primary concern for state formation appears to be the creation of legitimacy and ‘coherence’ in order to promote societal consensus. Thus, analyses of the people’s perspective and of the attempted production of legitimation are crucial. This concern lies behind the initiative of this workshop, which seeks to gain an accurate understanding of current processes of state formation in South Sudan.

Our hypothesis is that from a South Sudanese point of view, the imagined reality of the ‘state’ is currently under construction through negotiations and practices that allow for expectations and interests (regarding the state) to be expressed. Due to the participation of state bodies’ representatives, those negotiations and practices are labeled ‘governmental’: currently state bodies’ representatives are convincing not only the people but also themselves that the state as such exists and that they are its legitimate representatives.

In other words, the above-mentioned reductionist approach found in current research does not sufficiently take account of the complex interrelations of local, national, regional and international individual and collective actors involved in the processes of state formation. It ignores the deep(er) intricacies of collective identification processes and their interrelations in a changing societal context (Schlee and Watson 2009).

These collective identifications in the case of South Sudan are shaped by exposure to new technologies, ideas and cultural variations as well as by structures of (geo-) politics and policies. Interdependent endogenous and exogenous structures and models (e.g. local power relations, monopoly of violence, programs of DDR, Transitional Justice, Rule of law/Access to justice) have force and impact on state formation: they may be accepted, appropriated, adapted or resisted. Individual and collective actors give these structures meaning, through processes in which they articulate identities and position themselves (Schlee and Watson 2009).

Empirical data show that besides state bodies’ representatives, a complex array of social actors such as urban dwellers, returnees and IDPs, local and ethnic groupings, religious movements and institutions, employees of (I)NGOs, and inter-state agencies are involved in the negotiation processes of state formation. The negotiations include conventional debates with state agents but they also range from cooperation to resistance, and open and hidden adaptations.

Furthermore, state bodies’ representatives in particular are confronted with exposure to multiple sets of ideas and technologies of the ‘State’, and as a consequence the ideas of the state remain vague. Those ideas are translated in different practices, influencing state formation efforts.

The state appears to be a contentious resource for which individual and collective actors compete (Schlee 2003). Efforts are oriented towards securing and manifesting existing as well as expected future advantages, including control and power. In practice, however, these efforts may well turn out to narrow the negotiation space for the creation of a legal framework. Governmental actors therefore need to carefully balance the assertion of their personal or group interests, the acceptance of competing interests and the demands of international actors regarding the application of state laws and apparent promotion of a ‘coherent’ and ‘legitimate’ state, in order not to threaten the ‘project’ of state formation.

To achieve further progress in the ‘project’ of state formation and to gain internal and external recognition, normative regulations and the establishment of institutional frameworks such as a constitution or a nationality/citizenship law may prove to be relevant legal tools. Both, those normative frames themselves and the process of their formation open up spaces for negotiation where different actors, both from inside and outside South Sudan, including prefabricated models and ideas are, so to speak, brought to one table.

In the emerging South Sudanese state, negotiation processes are not very institutionalized, and that also includes the spaces of action and the participating actors. The ongoing discussions offer a unique opportunity to analyze the scope and influence of the multiple actors that are involved in such a process of state formation. In sum, our starting hypothesis for this workshop is a double hypothesis, based on two presuppositions, which we want to submit to the discussion: the first is that institutions and mechanisms – masks which prevent seeing political practice (Abrams 1988) – are not yet well established and routinized and thus do not yet obscure the negotiation of South Sudanese statehood. The second is that this absence to a certain extent facilitates the study of the political and legal processes and practices that accompany the formation of the South Sudanese State.

Thus, the focus of this workshop is on the inner-perspective based on long-term and empirical research, which is currently underrepresented but indeed crucial. The aim is to get at a deeper understanding of what kinds of negotiations take place and who is involved. Furthermore, it will examine how the South Sudanese state itself, as well as the perception the local population has of it, is shaped through those negotiations and what manifestations and outcomes become visible.

We propose the following key questions:

• What kind of negotiations and practices of state formation are taking place?

• Who participates in the negotiations of state formation in your particular case?

• How do people perceive the current state of South Sudan, its representatives and their practices? And through what kinds of actions (and non-actions) are these perceptions produced?

• What are the different current expectations that local actors have of the South Sudanese state?

• (How) does statehood manifest itself in the lives of individuals?

To address these questions, three main themes for individual contributions have been selected:

I. Post-conflict reconstruction

– Disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR)

– Infrastructural challenges

– Socio-economic reconstruction and cross-linking to neighboring countries

II. ‘Law and justice’

– Interplay of statutory and local normative orders

– Negotiating “citizenship” / nationality

– Transitional Justice (rehabilitation efforts, involved actors, institutions, etc.)

III. ‘Non-state’ actors

– “Diaspora” communities (returnees, IDPs)

– Religious movements

– (I)NGOs

Contact:

Timm Sureau, Tel: 00493452927147, email: sureau@eth.mpg.de

Katrin Seidel, Tel: 00493452927315, email: kseidel@eth.mpg.de

References

Abrams, Philip. 1988. “Notes on the Difficulty of Studying the State (1977).” Journal of Historical Sociology 1 (1): 58–89. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.1988.tb00004.x.

Krohn-Hansen, Christian, and Knut G Nustad, ed. 2005. State Formation: Anthropological Perspectives. London; Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto Press.

Schlee, Günther. 2003. “North-East Africa as a Region for the Study of Changing Identifications and Alliances.” Report // Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology 2002/2003: 163–170.

Schlee, Günther, and Elizabeth E. Watson. 2009. Changing Identifications and Alliances in North-East Africa: Volume II, Sudan, Uganda and the Ethiopia-Sudan Borderlands. Integration and Conflict Studies. New York: Berghahn Books.