‘[…] I will preserve and protect

The honour and independence of my country

With my life!’

First light: a deep purple over the edge of the camp, as the young conscripts bring themselves to attention on the parade square, their equipment arrayed neatly around them. The words of the Singapore Armed Forces (‘SAF’) Pledge echo across the dull brickwork, and across the camps and barracks where others, like them, are undergoing two years of mandatory military training – alongside a corps of regulars, reservists and a handful of volunteers.

Since 1967, all Singaporean males aged eighteen and above have been liable for full-time National Service (or ‘NS’, as it is better known), and around 25,000 of them join the ranks of the SAF yearly. Over five decades – and several generations of fathers and sons – NS has come to feature heavily in pop culture depictions of Singaporean life, its rituals of hardship and solidarity configured as a rite of passage. Indeed, beyond routine declarations of allegiance and acts of service, NS has become a touchstone of Singapore identity, if not of myth.

The close association between NS and nationhood, however, belies the fact that a significant number of these young soldiers are, in truth, foreign nationals. Current figures are hard to obtain, but in 2011 the Defence Minister revealed that 8,800 second-generation Permanent Residents (who are subject to the same obligations) had been conscripted in the preceding five years. When I joined up two years later, I met colleagues who held passports different to my own, and spoke a dazzling range of first and second languages. Many had relocated to Singapore with their parents at a much younger age, in search of work or better educational prospects.

Permanent Residency, in the words of one government website, is a legal status short of citizenship for those who have chosen to ‘call Singapore home’. In many liberal democracies, the status is seen as a pathway to citizenship, and guarantees individuals many of the same rights as citizens. By contrast, Permanent Residents in Singapore face a widening gap between their entitlements and those afforded to full citizens. Moreover, despite being liable for NS, Permanent Residents are not assured citizenship. On the contrary, those who do not fulfil their obligation, or renounce their status before being conscripted, risk being denied permission to work, study or remain in Singapore thereafter.

What would it mean for a non-citizen to leave his old life at the gates of the camp, and learn to shoot and kill in the name of another country?

What did it mean, day by day, for my peers who found themselves arms deep in the wet Singaporean mud, and were made to yell the words of the Pledge along with the rest of us – but whose position here, at the end of two years, was no less precarious? It would take me years, and my own journey through NS, to find out.

*

I first learned those words at eighteen, fresh out of school and cockily eager to see what all the fuss was about. Up to then, I had mostly gone to what were known, in Singapore’s no-nonsense patois, as ‘elite schools’: institutions which made no bones about the idea that we were crème de la crème, and hot-housed us into thinking that we were meant for greater things. Even NS – which at least in theory was meant to be a melting-pot of all backgrounds – promised to be a breeze. As we gleaned from friends and seniors, we would join a ‘leadership cohort’, and take a special regimen intended to test our suitability for positions in the officer corps.

As it turned out, I would not spend more than a few months in the army, before being granted leave to complete my studies overseas. By the time I made it back for the remainder of my two-year obligation, my time abroad had given me new ways of seeing the camp.

In one sense, it was a site of rigid hierarchies where our worst instincts of elitism and class snobbery, not to mention misogyny or racism, could too easily be amplified. At the same time, having done my postgraduate year in the rapidly-expanding field of Refugee Studies, I was inspired by how my professors were applying Agamben’s ideas on the ‘state of exception’ to the refugee camps at Calais and elsewhere, and realised that the army camp that I would soon return to also produced ‘bare life’, in its own way. While the citizen-conscript was perhaps the conceptual opposite of the stateless refugee, he was subject to arbitrary restrictions that, similarly, whittled down his sense of personhood and voice. With this in mind, I began to think of the army camp as an exceptional space, created as an exercise of state sovereignty, and meant to sustain that very sovereignty.

A new perspective on the camp wasn’t complete, though, without a sense of the lives within it. And partly because of the time I had spent advocating for refugee rights in the UK, partly to reckon with coming home to a country that felt so suddenly distant, I wanted to take a good, close look at the relationship between citizenship and conscription, two strange and powerful ideas in themselves, as it played out in the experiences of those around me.

So I hit the library. On weekends, as our officers released us to the outside world, I read about the Jourdan Law of 1798, which declared that ‘every Frenchman is a soldier and must defend his country’. In one stroke, the French First Republic consigned the feudal army to history, and brought a new political compact into being. Much wider citizenship rights were now on offer, in return for equally onerous responsibilities: the duty to die for one’s country, an old ethic made new. As the modern era unfolded, male conscription became tied to various citizenship entitlements, from housing to healthcare, as well as a slew of nation-building myths that equated a militaristic, masculine identity with service to the ‘fatherland’.

But could these myths still hold? Serving in a supply platoon with men of mixed nationalities, I was in the perfect position to observe how that centuries-old relationship was coming undone. For them, conscription was not so much tied to citizenship, but simply the price of living in the same city as their families, or retaining the option of making a life in it. Few intended to remain in Singapore for the rest of their careers – an unattractive prospect for these mobile millennials – and questions of national identity or allegiance seemed, at best, outmoded. The famous lines from the World War I poet, Wilfred Owen, came easily to mind. If the myth of ‘dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori’ had already rung hollow in his day, I had a hunch that here, in our basement storerooms, it had long lost its sway.

Writing an ethnography seemed the best way of getting at these questions, but I was also wary of starting on one. The discipline has had a troubled history in our region, and it is difficult, even for the most sensitive researcher, not to reproduce the fraught dynamics of knowledge production in a former colony. Yet here was an opportunity that I would not again have: to be conscripted alongside my interlocutors, subject to the same restrictions as them and, under the eye of our commanders, for a matter of months, to share in their hard work and heartaches.

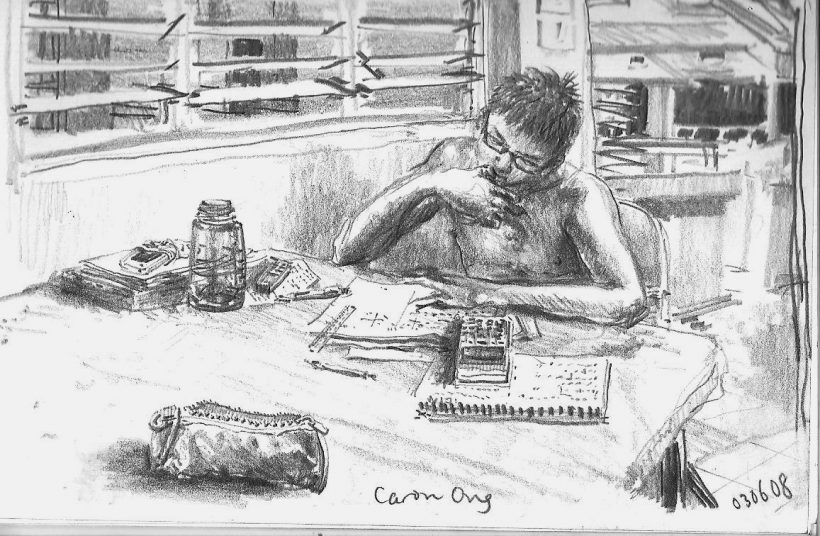

I began to take my notebook into camp: as a citizen, a conscript, and a collector of stories. My battalion were already my people. Now they would also be my ethnos.

*

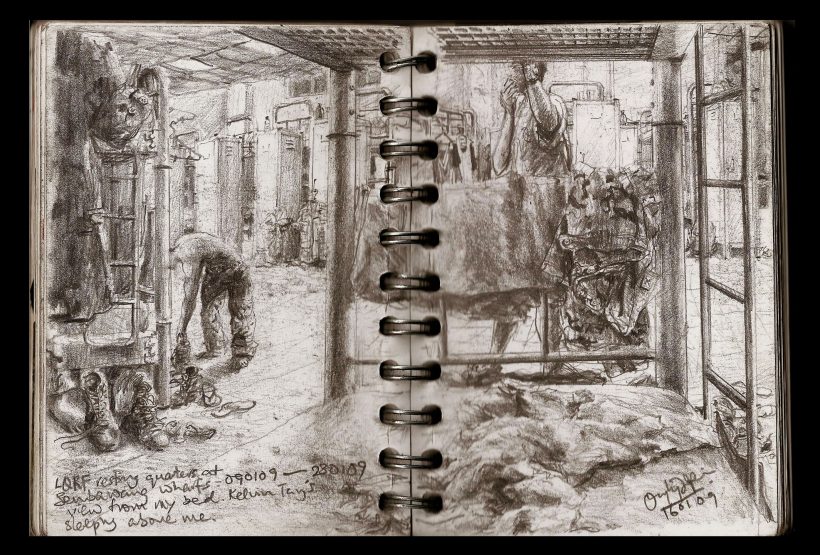

Even so, I didn’t know where to begin. I wanted to start conversations as naturally as possible, but where in the camp were the men truly at ease? In the bunks, there was always the risk of an impromptu spot-check; and given that it was where they had a semblance of private time, I was reluctant to intrude. The alternative was in the shade of the storerooms or garages, where the weight of their vocations would be especially salient. But encounters in these spaces were so contingent that I was rarely in the right place with my notebook at the right time.

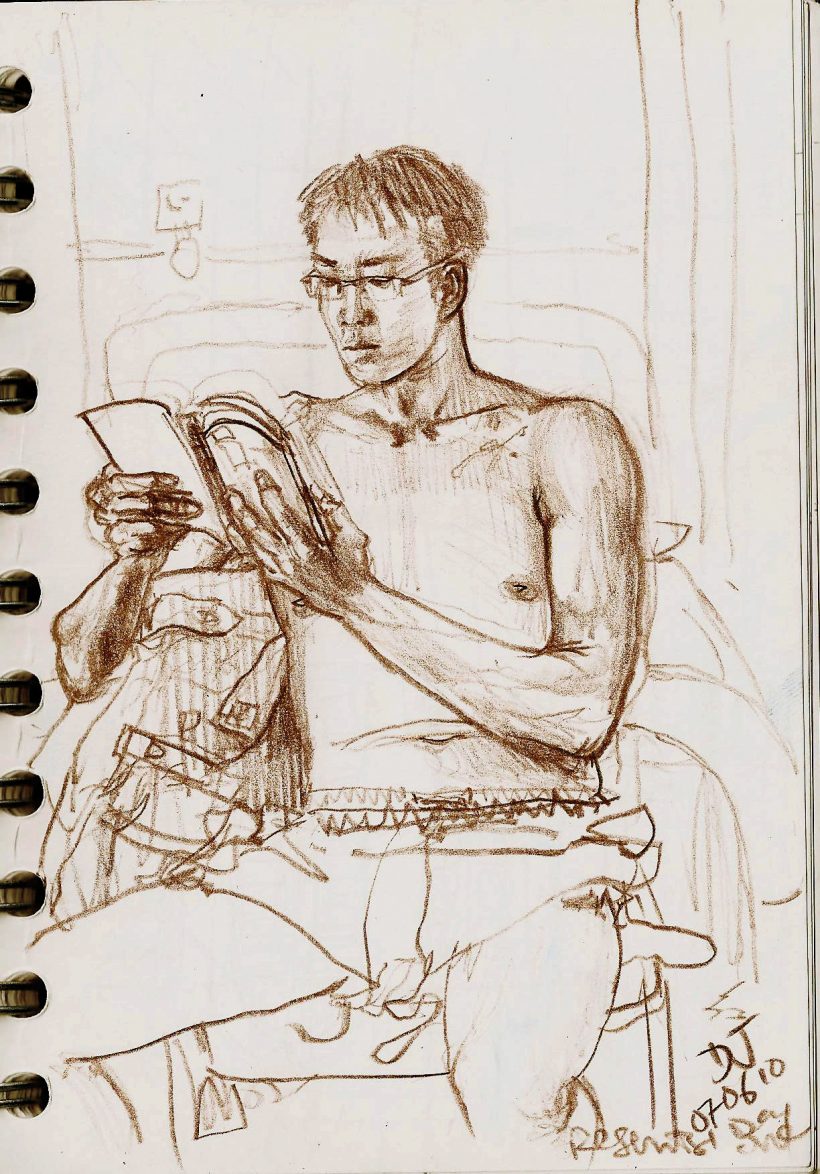

Eventually I decided on the office, which being air-conditioned was where the men retreated from the afternoon heat, to enjoy cookhouse desserts (ice-cream on Tuesdays, fruit otherwise) or sleep off the morning’s heavy lifting. It was also where hierarchies were established and solidarities formed, ‘dead time’ was made productive through gaming or small talk, and conversation flowed most freely across the manly distance created by a work-desk.

In this way I had the opportunity to interview fifteen men: citizens of China, India, Malaysia, Taiwan and the Philippines. All had come from very different social and familial backgrounds, and gained a wide range of experiences in the army. Some were designated as Supply Assistants, in charge of a range of logistical and (largely) menial tasks, while others were selected as commanders, and were trained as Officers or Specialists. Each had passed through quite different unit environments, and told stories that were in turn hilarious and harrowing .

With a few, talk flowed for more than an hour around the open-ended question of their dreams and plans. There were others with whom I sat down for several shorter conversations, interspersed with the demands of their official duties (or viral videos on Tiktok). The wider battalion became part of this process too as the other conscripts, overhearing my conversation with one of their friends, would so often step in to embellish a story or dispute a point.

At the end of each week, I parsed my notes from these conversations, reading and re-reading them against theoretical frameworks of duty and belonging. Unsurprisingly, their narratives were rich and varied. But some patterns emerged, and I was able to identify among them three ‘frames’, which I thought of as their ways of relating, and relating to, the ideas of citizenship and conscription. In the first, relational frame, which was most commonly held, conscription was seen as a mode of identification: as a carrier of personal or societal values – both desirable and not – that were seen as uniquely ‘Singaporean’. Others held a more transactional frame, where conscription represented a cost to be squared off against material entitlements linked to citizenship status; while a third, smallest group expressed an aspirational frame, where conscription was seen positively as a bridge to achieving their transnational ambitions, further afield.

Thinking about all this outside of a formal academic institution was a challenge, and I took every opportunity to test my ideas with anyone who could be prevailed upon to sit down for a cup of coffee. I was fortunate, too, to be able to share some of the work in its gestational phases with an informal workshop of researchers studying aspects of forced migration in Singapore, and at a bustling conference in Sydney, a world away from the starched silence of the camp. For most of the time, though, my best confidants – and sternest critics – were the men themselves, who forced me to clarify my ideas, and perhaps most importantly, made sure I was having fun.

*

As the months in the camp wore on, the office became the site of many other observations, not all of which were directly related to my project, but which spilled easily into a series of brief sketches and longer essays. These ‘field-notes’, as I called them – only half ironically – made their way to friends near and far, telling them how I was getting on in the army, and sharing a little of the NS experience with those abroad. What I didn’t realise then was how much the writing would help me, too, make sense of the upheavals and transitions in my own life, and nudge me towards a way of understanding myself again in this city I had grown up in.

Returning home, after all, hadn’t been easy. Against the backdrop of Trump’s election victory and the interminable Brexit process, my classmates from grad school were off to do big things in the world: advocating for undocumented children in New York, or fighting human trafficking in the Mediterranean. They had taught me to recognise my obligations to distant strangers, but back here, conscripted on a small island, what were my obligations to those who served beside me in the camp?

Day by day, my informants drew closer to completing their period of conscription, and we celebrated the end of their NS together, with what simple snacks we could carry with us into camp. I continued to meet with some afterwards, as they struck out to turn the aspirations they had shared with me into reality: some taking on part-time jobs to support their families and others, against all odds, going to university. By the time I felt ready to share my research with an academic audience, all of them had returned safely into the civilian world, and begun new lives., I sent off the draft of the paper I had written – containing as many of their voices as I could weave into my narrative – on the day I left camp for the last time.

We, who finished our time unscathed, were the lucky ones.

In late 2018, news broke that Liu Kai, a full-time National Serviceman conscripted around the same time as us, had been killed in a training accident. It had not been a good year for the SAF: a series of conscript deaths, including one in an elite Guards unit, had already prompted public outcry and serious soul-searching. But this was different. Observers pointed out that Liu had been a citizen of the People’s Republic of China, and a Permanent Resident in Singapore. On the popular internet forum Hardware Zone, some wondered why a non-citizen would give his life for a country that wasn’t his ‘homeland’, while others hit back with statements of solidarity: ‘since he served NS, I consider him [a] true blue Singaporean’. Most commenters were quick to count Liu as one of ‘our boys’.

At the time, the same sentiments echoed around the camp, in snatches of conversation in the cookhouse and corridors. Yet who were we to speculate on the value of a life? None of us would ever know what Liu was thinking at the end, whether he felt, in those final moments, if he was making good on the Pledge’s too-heavy words. All we could do was ask the same of ourselves: what did it mean, after all, to be serving out this time ‘with our lives’?

No ethnography, I knew, could possibly answer this question, and I hardly knew if I could answer it for myself. But I was glad for the window I had been given into the lives of these men – and in the end, for what precious and dreaming lives they were.

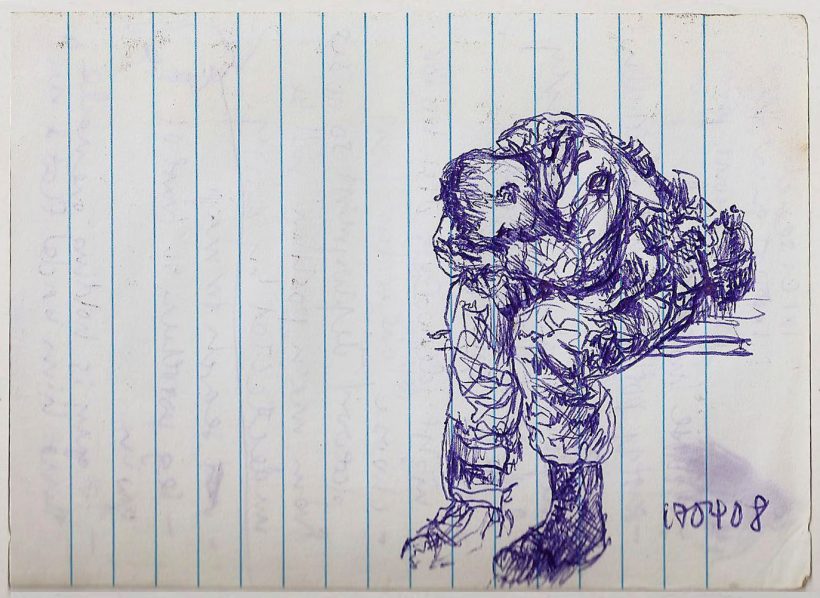

Featured image by Alvin Ong.