In Brazilian squats, a ‘local population struggles for their ‘right to the city’ and a ‘migrant’ population tries to establish and improve their lives (temporarily) in multiple places simultaneously. These different processes and experiences of displacement and emplacement correspond, intertwine and, eventually, can also contradict each other.

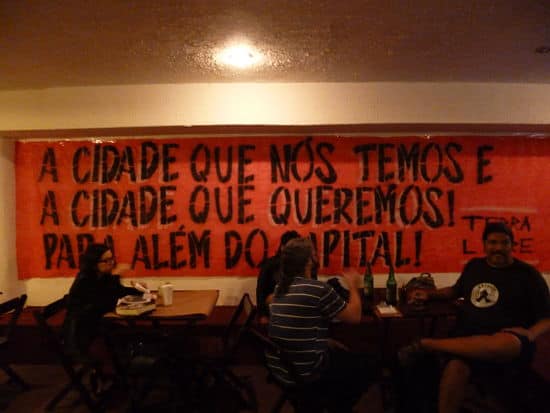

Everybody listened while Isabel[1] talked seemingly endlessly, nobody interrupted her. Isabel was obviously in a bad mood. A Brazilian woman in her 60s, who had fought against the fascist military regime half a century earlier, she knew how to draw the attention of the group sitting around her, mainly young men and a few women – migrants and refugees from different African, Asian and some Latin American countries who had reached the city of São Paulo within the last year. They were all inhabitants of this squat in the ancient city center and had, thereby, automatically become part of the Frente de Luta por Moradia (FLM), one of several social movements that had emerged as a response to the privatization of public space. This and other comparable social movements have been making use of the absence of the state in the policy field of urban living since the early 1990s; they appropriate buildings that have been vacated by the housing market and, subsequently, resignify national law, in which the social meaning of property is confirmed as a protected social right (Earle 2017).

Isabel, one of the movement’s leading figures, had arranged a meeting on this particular day to express her deep frustration about the migrants’ lack of integration into the movement’s social and cultural activities. Isabel talked for more than 30 minutes, admonishing the inhabitants regarding the importance of participating in the active, political struggle against the neoliberal effects of segregation, gentrification and economic precarization.

Here, at this place, it does not matter where you come from. We are all the same, we are all poor, we’re all displaced. You understand: We are all displaced! We all fight the same fight. This is not your home! Living in this building means being part of a political struggle. You cannot expect to live here and do nothing. The moment that we stop struggling, we will receive nothing. And you have to go back sleeping in the street. (translated from Portuguese).

“Deslocamento” (displacement), one of the key words in Isabel’s statements, is a powerful term in contemporary Brazil. Firstly, it is used by the political left to sensitize about the multiple different types of losses that people experience when their belonging to a specific place is forcibly taken away. This can occur, for instance, through the dispossessive forces of, urban regeneration projects, agrarian land reforms or man-made environmental disasters caused by mega-dam constructions and mining operations. When Isabel questions the meaning of home (“this is not your home”), she challenges the social value of property per se. For political activists like her, living in an occupied building needs to be understood as a particular means to an end, a political act which strives towards the collectivizing of basic needs, such as access to housing. Secondly, the notion of displacement can also refer to a policy-oriented, often humanitarian category of ‘displaced persons,’ which intends to capture the specific experience of being involuntarily on the move, especially among those who had to leave their familiar social conditions in and through a context of war, violence and emergency. Hence, deslocamento, in this context, carries both connotations: It can denote unifying sameness, but also a politically laden category of difference.

While the other persons present listened patiently, I felt irritated. I was wondering about the different experiences of deslocamento that apparently merged in this large room. My gaze fell on Dosnel, a self-assured Haitian man in his late 30s, who sat silently next to Isabel, looking his hands in his lap. Last week he had shown me his room on the 11th floor; he lived there together with his wife Guerline and their baby. “We came from all over: Africa, Haiti, India, even China. Several other families also came from Haiti,” he said in a mixture of French and Kriolu, while we were climbing up the dusty, dimly lit stairs to their small, lovingly and precisely furnished room, which consisted mainly of a large bed, a chest, a small wardrobe and a tiny kitchenette, comprising an electric stove and a fridge. The garland of plastic flowers that surrounded the small flat screen on the green-painted plywood wall undeniably completed the look of a homely home, an intimate place of belonging that reflected its inhabitants esthetic sense of care.

Dosnel and Guerline were obviously proud of this little private space they had created after a long trajectory following the devastating earthquake that had destroyed large parts of their country in January 2010. While we waited for the little electric stove to heat up some rice and beans, the two showed me pictures of the house they had lost in Jacmel, a small town on the country’s southern coast, which had been hit particularly heavily. When they left for the Dominican Republic, where some of their friends had already been staying for several years, the two had to leave behind a son and a daughter, both teenagers, with Guerline’s parents. This is where they had heard about the humanitarian offer provided by the Brazilian government through their UN mission, MINUSTAH. As a response to the devastating earthquake, Brazil had created an exceptional ‘humanitarian visa’ that granted a certain number of Brazilian visas to Haitian nationals per year (Moulin & Thomaz 2016). “We knew we could come to Brazil, that they would receive us here, but the way was still long,” Dosnel explained. After flying from Santo Domingo to Ecuador’s capital Quito, they took an overland bus to Iñapari, stayed for several weeks in Brasiléia, a small town in the northern state of Acre, where they had to wait another three weeks before they were taken by bus to the city of São Paulo. Here, they stayed the maximum of three months at the casa to migrante, a shelter provided by the Catholic missão paz (peace mission).

The two praised the support they had received from the Catholic mission: “We really felt well protected. This city is a dangerous place, but in the casa [the mission] everybody took good care of us. If you don’t know the city and you don’t know any Brazilian, this is what you need,” Dosnel explained. Guerline also continued to reflect on the temporary nature of their stay at the missão:

At the beginning they told us that we would get permission to stay for some weeks, and that we then have to leave and search for another place. I liked it there, at the casa. But we were not supposed to stay. At the same time, everybody was building in Haiti. We heard that they were rebuilding the city with their hands. My parents had moved to another house. We also wanted to contribute. We wanted to work [“We needed a job,” Dosnel agreed] and make some money and send it to Haiti to help with the reconstruction. That’s why we needed our own place, one where we could stay.

Guerline’s statement reveals a crucial paradox that not only shelters but humanitarian organizations share generally: On the one hand, they offer a space of arrival and inclusion where one can settle down. Most recent arrivals, especially at the very beginning of their stay, translate the controlled and securitized character of shelters into feelings of protection against the perceived dangers of a city life on the move. Some inhabitants of shelters, however, complain about this monitoring, which is symbolized through strict house rules and a daily routine which allows entry and free circulation only during certain hours. On the other hand, this spatial fixing and regulating by institutional logics is contradicted by the constant reminder that their stay will certainly remain temporally limited. Most public shelters work with a maximum duration of stay, which will only tentatively be communicated at the moment of entry. The esthetics of collective dormitories and dining halls, which undermine any feeling of individual privacy and agency, underline the provisionary nature of a person’s stay. Finding one’s place under institutionalized conditions of displacement remains a challenge.

Comparable to many transmigrants whose lives span across borders and who simultaneously feel attached to more than one place, Dosnel and Guerline searched for a way to establish their lives in São Paulo, which would allow them to also remain present in Haiti, where their family expected their active contribution to this process of reconstruction. Together with Nanneke Winters, I have argued for focusing on emerging trajectories of ‘transitory emplacement’ to understand the multiple encounters between a dynamic migrant population and local actors, and the locally specific implications of these encounters to understand how migrants get information and emotional support by linking up with local communities and keeping in touch with family and friends abroad (Drotbohm & Winters 2018).

At his workplace at a food factory, Dosnel got in touch with another migrant who lived in one of São Paulo’s squats which belonged to the Frente de Luta por Moradia (FLM) – a social movement targeting the interests of those who struggle for decent living. Continuing to describe their trajectory, Dosnel and Guerline talked about the strict rules that were applied by their mouvman (the movement), especially regarding the acceptance of new inhabitants. “They don’t accept just anybody who is simply looking for a good place to stay. In this city, so many people live on the streets. That’s why they have to choose.” Living in an occupied building is cheap compared to a regular apartment. The two of them pay only 200 Rs (approximately US$ 60), which allows them to send the largest part of their income back to Haiti. While Dosnel described the procedure of admission: The form they had to fill in, the assembly in front of which they had to present themselves and the house rules they had to learn, Guerline showed me the movement’s membership card, which is used for documenting her participation at the atos – political acts which demonstrate the movement’s active membership, such as a demonstration or uma invasão, the invasion and occupation of an empty building, which often entails confrontation with police violence. Dosnel continued his explanation:

This occupation is very well organized; everybody knows what he or she has to do. We have a committee for cleaning, one for organizing the library, and we have a doorman [gadyen] who keeps thieves or other criminals outside.

Heike: “What about your participation in the political struggle?”

Yes, this is also very important. They contact us via WhatsApp. When I am at work, I receive a message, and I will see whether I can go. It depends. A demonstration is possible, they usually take place on Sundays. If I don’t work on Sundays, I go. But we are many. Not everybody has to participate.

Dosnel apparently interpreted the request to engage more actively in the luta (the political struggle) as a formal requirement for living in the squat. According to him, these relatively strict rules needed to be accepted in any type of collective housing which would provide physical protection, social integration and eventually the access to some kind of upward or middle-class social mobility. I found this statement paradoxical, as the lives of the more-and-more self-segregating middle classes is what the Brazilian activists actually struggle against.

My mind returns to the meeting and to Isabel’s voice when she talked about the ultimate social state in contemporary urban Brazil, in which millions are being dispossessed of the spaces they have formerly called their homes and have to live in favelas or on the open streets. While my eyes turn to the window and wander over the seemingly endless sea of surrounding buildings, I listen to Isabel’s clear positioning in the collective anti-capitalist struggle and the movement’s aims, which would certainly strengthen the interests of the urban poor, the inhabitants of favelas, other types of irregular housing and mobile populations coming from other countries and continents.

Different processes and experiences of displacement and emplacement correspond, intertwine and, eventually, can also contradict each other in these squats in which several groups live, interact and strive towards a more decent way of living. On the one hand, we have a ‘local’ population struggling for their right to the city and, on the other hand, a ‘migrant’ population trying to establish their lives (temporarily) and strive towards a middle-class position in multiple places simultaneously. While they all manage to construct new sociabilities and forms of social belonging (Glick Schiller & Çağlar 2016), these processes of emplacement are apparently filled with controversial expectations and ideas when they refer to a physical place, signified through an address or a doorman, or to a transnational family life extending beyond borders, or to a social movement in which a common political agenda is shared. In the end, all these marginalized actors position themselves in relation to power asymmetries in which the reliability of place and social belonging cannot be considered self-evident.

References:

Drotbohm, Heike & Nanneke Winters 2018: Transnational Lives en Route: African Trajectories of Displacement and Emplacement across Central America. Working Papers of the Department of Anthropology and African Studies of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, 175.

Earle, Lucy 2017: Transgressive Citizenship and the Struggle for Social Justice: The Right to the City in São Paulo. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Glick Schiller, Nina & Ayse Çağlar 2016: Displacement, emplacement and migrant newcomers: rethinking urban sociabilities within multiscalar power. Identities, 23:1, 17-34, DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2015.1016520

Moulin, Carolina & Diana Thomaz 2016: The tactical politics of ‘humanitarian’ immigration: negotiating stasis, enacting mobility. Citizenship Studies, 20:5, 595-609.

[1] All names are pseudonyms.