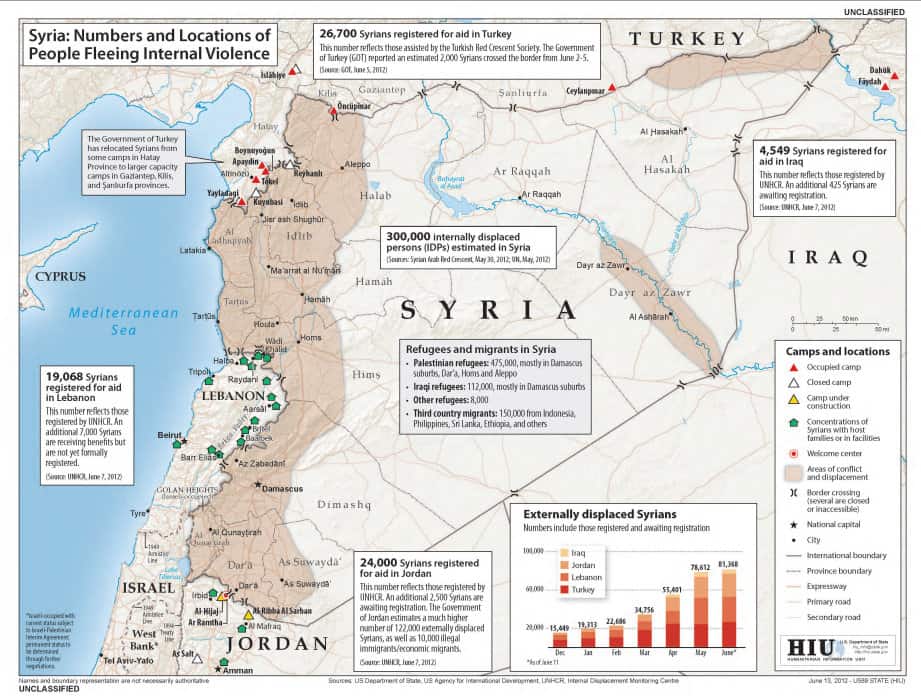

Over the past five years, Syria is going through an unprecedented internal crisis and a civil war generating extreme violence and insecurity. Since the outbreak of the uprising in 2011, Syrian civilians have been forced to flee their homes, cross the borders and seek protection in neighboring countries such as Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, Egypt and Jordan. According to the latest UNHCR data, 3,726,988 Syrian refugees are registered in this part of the Middle East Region (1), including 619,160 in Jordan. Representing approximately one tenth of its population, the country hardly managed such an important influx of refugees and has rapidly needed external assistance to respond to the Syrian crisis. For that reason, camps have been established, since then managed by UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency (whose role is to provide assistance and protection to refugees and other persons of concern), in collaboration with a wide range of humanitarian partners and NGO’s.

While about 80% of Syrian refugees live in Jordan urban and rural areas, the remaining 20 percent live confined in those camps. Although not explicitly prescribed by the 1951 Geneva Convention (2), such solution rapidly became a political compromise between, on one hand, an immediate response to the refugees’ need of protection and, on the other, the security and economic concerns of host states.

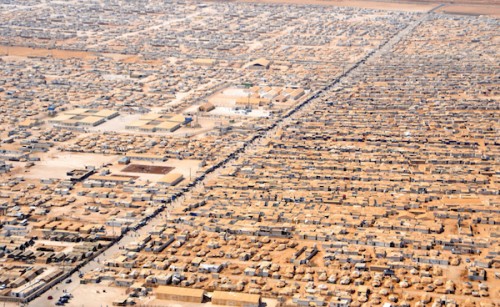

Opened in July 2012, in a windswept desert located 10 km east of the city of Mafraq, the refugee camp of Zaatari was initially conceived for temporary purpose. However, due to the continuing Syrian conflict and the lack of resettlement/relocation policies in European and neighboring countries, the camp progressively expanded, now welcoming between 80,000 and 93,000 refugees (3) and covering more than 530 hectares (4), making of Zaatari the world’s second-largest refugee camp and the fourth largest city in Jordan. And yet it might be recalled that the long-term encampment situation faced by Syrian refugees in Zaatari is far from being an isolated case.

On the contrary, the issue of refugees awaiting for voluntary repatriation but finding themselves without the ability to return has been conceptualized by the UNHCR as a protracted refugee situation (PRS); a major one being where more than 25,000 refugees have been in exile for more than five years (5). Similarly to Rwandan refugee camps in Uganda or Bhutanese in Nepal, Syrian refugees are left with few options since they are restricted from permanently settling within the host state (Jordan) and unable to return to their country as long as the civil war persists. (6) At the initial stage, encampment has therefore the merit of offering an immediate response to the urgent needs of refugees, providing them with food, shelter or medical assistance.

However, once the state of emergency draws to an end, an assistance limited to staple products and basic commodities appear no longer adapted to the needs of the camp’s inhabitants.

By force of circumstances, the camp undergoes a progressive transformation. People’s needs and expectations evolve from material assistance and food aid to more sustainable livelihoods: a safe and healthy environment, more spacious places to live, a greater autonomy and, above all, recognized rights. For that reason, considering Zaatari only as a “refugee camp”, in its sole external and artificial dimension, might appear a bit simplistic. Inside, interactions and exchanges between people dominate. Consequently, when encampment lasts for years and that perspective of imminent return is almost inexistent, may we assume that life in refugee camps necessarily turns into a new, although incipient, form of society?

From individuals to community

Indeed, unlike standard asylum, relocation and resettlement procedures, a refugee camp has the particularity of being an interim protection measure for groups of people, independently of a deep and full individual assessment. Inevitably, longer is the encampment, stronger is the social and collective dimension among such (groups of) people, obliged to share living spaces with people who may differ in class background, political, ethnic, family status or religious affiliation (7). Obviously, such forced cohabitation (implying physical proximity, sharing facilities, lack of privacy etc.) is likely to cause frustrations, misunderstandings, antisocial or violent behaviors. In the long-run, a regulatory framework is therefore needed to ensure security and stability in the camp, which refugees themselves are usually aware of. Indeed, although not always apparent and somewhat subjective, it has been observed (for instance in African refugee camps) that people might show – what has been called – a ‘’legal consciousness”, i.e. by developing a special relationship to legal rules, spontaneously claiming for justice or equity and refusing to live in a “state of exception”, where they would be deprived of any legal rights(8). Although in practice the entitlement of refugees effectively to claim rights due in theory is quite difficult or uncertain in camps or temporary settlements (which are supposed to remain interim measures), UNHCR strives at least to ensure the effective application of the international refugee protection regime (mainly governed by the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol relating to the status of refugees).

But the most striking example of such ‘’communitisation” remains the progressive transformation of Zaatari from an ordinary camp towards a city structure. Indeed, after months (and now years) of encampment, the camp management has faced diverse service-related challenges, mainly due to waves of new arrivals. On the initiative of UNHCR, more than 20,000 prefabricated caravans (replacing traditional tents) have been distributed, electricity supply and clean-up of electrical wiring became a priority issue, new cycle of voucher and in-kind distributions have been launched in collaboration with World Food Programme (WFP) etc.

Besides formal adaptations, other changes, led by refugees themselves, occurred in the camp’s daily life: shops and business have been set up in the main streets of Zaatari, ranging from supermarkets, bakeries to jewelry stores, hairdressers or media stores; electricity grids and energy supply have been diverted by Syrian engineers/electricians in order to get more autonomous access; a dozen of district and street leaders have been chosen among the population, in order to prevent and to solve daily conflicts (related to water or food distribution, civil litigations…) and to play the role of intermediaries between inhabitants and the managing authority.

More generally, the very basis of a democratic society is progressively emerging from this precarious and singular situation, notably through a collective management of energetic resources and the forthcoming establishment of district and local councils.

The long-term encampment process of Zaatari and its legal consequences

However, despite people’s good-will, solidarity or determination, the persisting encampment situation in Zaatari still remains preoccupying. Legality of such phenomenon with regard to International law has also been seriously questioned in previous studies and academic contributions, especially in terms of human rights law (the idea being that beyond the very International refugee law, human rights law should apply as an independent body to refugees by virtue of their human being (9)). It is indeed stated that a prolonged encampment affects and endangers some of the most fundamental human rights and liberties granted by International treaties and conventions: the right to freedom of movement, the right to work, the right to education, the right to freedom from torture or from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, etc.(10)

Obviously, long-term encampment has negative implications on people’s rights: confinement in restricted areas, with only limited and temporary permits to leave, does not comply with the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of states, as enshrined in Article 13 (1) UDHR and Article 12 ICCPR. Additionally, due to the camp’s structure and its remote location, the right to work, consecrated by Article 23 UDHR and Article 6 ICESCR, is infringed by long-term encampment.

Even if some commercial activities take place in the camp, real employment opportunities and integration in the Jordan labor market remain severely limited for Zaatari inhabitants.

That being said, those authors usually adopt an approach focused on individuals and place the person’s rights at the very core of the legal analysis, while it might also be interesting (and in this case, perhaps more coherent) to somehow replace those human rights in a “collective” perspective, even comparing such a camp to a community or a small society. In this logic, legal consequences of long-term encampment could be assessed at three different levels of the camp’s organization, i.e. the political, judicial and administrative dimensions.

First, regarding political rights and the conduct of public affairs: while the camp has been divided in 12 districts and is currently headed by temporary leaders, designation of people’s representatives might become a complex issue if encampment persists. Article 21 UDHR and 24 ICCPR guarantee everyone the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives, to vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections. Yet, during such exceptional circumstances, refugees find themselves in a “legal limbo”: on one hand, they are deprived of their rights to vote both in the host state and the country of origin, on the other, they are not legally entitled to claim for a fair and equal participation/representation in decision-making process carried out inside or outside the camp.

Secondly, future judicial organization might also become a matter of concern, given that International Law explicitly provides for the right to a fair trial, the access to courts and the principle of equality before the law (Article 10 UDHR, Article 14 ICCPR). Once again, in case of long-term encampment, it appears that neither UNHCR nor local district leaders will be competent to deal with criminal charges or civil litigations. As pointed out by Goodwin-Gin and McAdam, punishment, discipline or police are appropriate functions neither for international organizations nor for refugees themselves, for want of representative capacity and overall accountability. (11) In addition, people are entitled by law to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law.

Consequently, in the absence of durable solution, an alternative could be to facilitate access to Jordan courts and tribunals for refugees, providing them at least with legal assistance, effective remedies and a non-discriminatory treatment of their cases.

Thirdly, administrative obstacles and deficiencies have already been felt in the camp of Zaatari. It is especially the case for birth certificates and civil status registration (12), while birth registration is a right of all children under International law (13). Given that registration and certificates are issued by Jordan authorities (in that case, the Civil Registry in Mafraq), a strong collaboration between UNHCR and the host state is needed. Still, many Syrian refugees encounter practical difficulties due to their inability to provide the documents required (identity paper, marriage certificates…), which leads to serious consequences for unregistered child who might face higher risks of exposure to violence, abuse or exploitations and have future difficulty accessing national services as healthcare, employment or education. Even further, in case of persisting encampment, the current legal framework regarding nationality in Jordan and Syria might also become unfavorable – or even increase risk of statelessness – for children born in the camp. Indeed, in both countries’ legislations, establishment or acquisition of the nationality is based on the paternal filiation (jus sanguinis), while it is not legally permitted for women to confer Syrian or Jordan nationality on their children.(14)

However, in order to conform to their legal international obligations (15), many Arab countries amended or adapted their legislations in order to admit maternal filiation in exceptional circumstances. But in practice, those national legislations (almost) always impose additional requirements: in Syria, maternal descent is taken into account when nationality cannot be attributed by the father but it “needs to be supported by birth on the territory”. Jordan, for its part, exceptionally admits attribution of nationality by jus soli (right of the soil) in order to prevent cases of statelessness but only if the child is born of unknown parents (16). In this logic, a situation of a child born in the camp of Zaatari, from a Syrian mother and a father stateless or of unknown nationality (17) might appear quite problematic.

Towards durable protection and higher political involvement?

Secondly, refugees’ protection cannot be limited to temporary response or short-term initiatives. As clearly demonstrated by the case of Zaatari, beyond the emergency stage, a stronger protection framework is needed, especially through human rights standards and effective enforcement mechanisms. This cannot be reached however without external support and assistance from both international organizations and host countries. While the former should better adapt structures of the camp over time, optimize the social organization and progressively grant refugees greater autonomy, host countries’ stronger involvement and support is not only welcomed but will soon become a matter of necessity. In fact, considering its geographical expansion and its population growth, the camp of Zaatari could progressively reach the borders of surrounding Jordan towns.

If this situation arises, would not it be preferable for the host state to involve in the protection response, especially at later stages, in order to optimize – and directly benefit from – this singular source of immigration?

Indeed, once the emergency phase is over, facilitating access to Jordan judicial, administrative or civil structures and ensuring smoother transition towards relocation could already improve life conditions of thousands of refugees currently residing in the camp of Zaatari; at least while waiting for a definitive resettlement, a permanent integration and the beginning of a new life.

Notes

(1) UNHCR, The UN refugee Agency, Syria Regional Refugee Response: Inter-agency Information Sharing Portal, Last updated 12 Feb 2015.

(2) 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees

(3) Based on UNHCR population figures from February 2014 to February 2015

(4) UNITAR, UN Institute for training and research, satellite data of the Al Zaatari refugee camp, 7 January 2014.

(5) G.LOESCHER, J. MILNER, Protracted displacement: understanding the challenge, forced migration review (FMR), 33, September 2009, pp. 9-11

(6) S. SYTNIK, Rights Displaced: The Effects of long-term encampment on the Human rights of refugees, Refugee Law Initiative, working paper 4, May 2012.

(7) E. HOLZER, What Happens to Law in a Refugee Camp?, Law & Society Review Volume 47, Issue 4, December 2013, p. 847

(8) E.HOLZER, op.cit., p. 840, S. SILBEY, After Legal Consciousness, 2005, 1 Annual Rev. of Law and Social Science 323–68

(9) See for instance B. HARRELL-BOND, Can Humanitarian Work with Refugees Be Humane?, Human Rights Quarterly 24, 2002, 51–85; J. HATHAWAY, Reconceiving Refugee Law as Human Rights Protection, Journal of Refugee Studies 4, 1991; A. BETTS, Towards A ‘Soft Law’ Framework for the Protection of Vulnerable Irregular Migrants, 22 International Journal of Refugee Law 209, 2010 etc.

(10) See in this regard S. SYTNIK, Rights Displaced: The Effects of long-term encampment on the Human rights of refugees, Refugee Law Initiative, working paper 4, May 2012 or E. FERRIS, E., Protracted Refugee Situations, Human Rights and Civil Society, in Loescher, G., Milner, J., Newman, E. and Troeller, G., (eds.) Protracted Refugee Situations: Political, Human Rights and Security Implications, New York: United Nations UP, 2008, 85-107. Among other negative social consequences stressed by authors, might be quoted: the increase of disease and violence, the segregation of the host population, the lack of economic independence, the incompatibility with the local settlement first goal etc. (e.g. A. Schmidt, B. Diken, G. Verdirame)

(11) G.S. GOODWIN-GIL, J. McADAM, The refugee in International Law, Oxford, third edition, P. 471

(12) In November 2013, a UNHCR’s report revealed that over 1400 children in the camp born between the end of November 2012 and the end of July 2013 had not received birth certificate (UNHCR, The Future of Syria : Refugee children in crisis, 2013, p. 55)

(13) e.g. Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 24 ICCPR

(14) G.P. PAROLIN, Citizenship in the Arab World: Kin, Religion and Nation-State, IMSCOE, Amsterdam University press, 2009, P. 95

(15) E.g. UN Convention on the Elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (CEDAW)

(16) Jordan Law No. 6 of 1954 on Nationality (last amended 1987), 1 January 1954.

(17) For instance, Kurds people called ‘’maktoumeen”, unregistered and stateless in Syria. (See e.g. UNHCR, Lacking a nationality, some refugees from Syria face acute risks, December 2013)