This post is the third installment of our thread on the Moving Matters Traveling Workshop (MMTW), a project that explores migration and mobility by developing artwork, exhibitions, performances and public interventions. The MMTW will be at the Berlin Wall Memorial from June 1 to July 2. In the first installment, anthropologist and writer Helen Faller talked to Susan Ossman, Artistic Director of MMTW and in part two, performance artist Priya Srinivasan reflected on movement.

The Hairpin (AB): Do you think that only legs can take you this far? And only four of them for that matter? Look at me, I have none, but I’ve been carried around by two-legged people and I crossed so many borders, and sometimes borders crossed me. If you stay long enough in one place, the borders will surely change. Nobody remembers this and acts as if they are eternal. Sometimes humans build enormous walls to mark the borders too, and make them real. Tell me, how did you get to this museum, to Amsterdam?

The Golden Horse (OS): ‘Why’ is not a question to ask. Sometimes life seems like a chain of events you have no control over. There are decisions made elsewhere and you can be stuck in one place or rushed to another, and when asked afterwards if you had a plan, not to look a fool you just make up an answer.

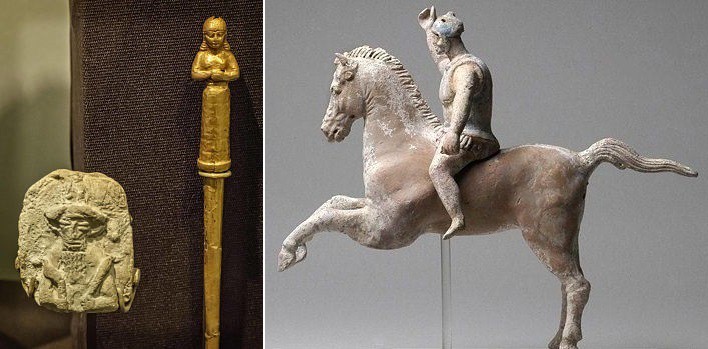

My four legs may come handy when one needs to gallop. But that was never my story. I was born in the mind of a goldsmith and wrought in the flames of his workshop in Alexandria. I was made to accompany my master to his grave. But these origins did not define my destiny. Like you, I crossed several borders, but the first one to traverse was between life and death. From what I see you must know a thing or two about death. What’s that tarnish that spoils your shine? Gold does not rust…

The Hairpin (AB): Blood does. And I have seen more than my share. I have been used as deadly weapon more than once. A disenchanted princess slipped me from her silky hair, straight across the throat of her unsuspecting brother. She then had free reign to expand the territory of the kingdom and rename cities in her family’s honor. Humans love drawing lines with blood. I could tell you so many more stories about how I was caught up in battles about border lines before I was judged so precious that I had to give up an active life and become a part of this collection.

Here, in the glass case, I am stared at by people who have no idea who I really am — like with a serial migrant: people know you are a stranger, but they cannot see the complex history until it is studied and presented to them.

The Golden Horse (OS): Archeologists and curators know our provenance but they often find it hard to verify our travels. They make us famous with articles and catalogues – at last count my image has appeared in over 20 books and at least 45 articles, most in top-tiered journals according to what I’ve heard from the grad students studying me at present.

The Hairpin (AB): But then there was that group of humans who did tell our stories. What an exciting time it was when they were running all around the museum, making music and placing strange new objects in our midst.

The Golden Horse (OS): Yes, they got a few details wrong, but it certainly was exciting. You know, that one “Olga” who played me comes back with her students. She talks about the meaning performing has for her “as a sociologist.” She tells them about the MMTW- apparently these people have all lived in numerous countries. They travel together to make art and show and perform it. They went to Bucharest in 2015 and California in 2016.

Here we are again, improvising another dialogue between the golden horse of ancient Egypt and the hairpin of a Mesopotamian princess – this time on the digital page of Allegra. The pin and the horse were characters in a performance that we staged at the Allard Pierson Museum of Mediterranean Antiquities in Amsterdam in 2014 with the MMTW. The theme was “Objects in/of Migration.” We developed the performances by studying the significance of things in each of the 15 participants’ path of migration.

What is the work that objects do or fail to do in stitching together biographies, friendships and love stories of people on the move? What do they obscure and conceal when they become a focus of gaze and objects in a collection?

We collaboratively developed a performance that was, literally, a passage. It began in the museum cafe where Priya Srinivasan mesmerized attendants with her Shiva dance. She led the audience to the stairs, which they succeeded in climbing after several starts and stops, songs and poems and stories. They emerged into a large room where Alec and I became the Hairpin and the Golden Horse in performance that shifted between the world of humans and that of things. What I remember distinctly is how quickly the space itself prompted us to step out of our personal stories, the museum collection, its history, the context of Amsterdam; these created a special intertextual, dialogical space.

For instance, artist Alejandro Ramirez boldly added present-day objects to the museum cases: a plastic water container (Evian brand), a dirty running shoe (Reebok), a used toothbrush (Braun), a portrait of a woman (a selfie?). The objects mascaraded as museum items – Alejandro’s annotations looked just like the ones for the official collection items. He brought to the open an asymmetry that defines the relationship between people, cultures and territories.

The Hairpin (AB): To me performance creates an unmediated relationship between the body and theory on the one hand, and between the theory and the public on the other. It is embodied theoretical discourse, rendered accessible. There is a need to better communicate ideas that are enveloped in the often-times hermetic academic discourse. Contemporary art also tends to be quite elitist and hermetic. Pushed by the market logic of creating value through distinction, a lot of artists generate increasingly remote, hard to access work. Today, when the question of “the other” is made again visible by the refugee crises, and when the dominant and unfortunately more intelligible discourses are those of closing doors and building walls, we need to find ways to communicate ideas to a broader public.

The question of access is also important. There are spaces, for example, in which not everybody feels entitled to enter (including museums). I think that we need to re-evaluate and re-value the political power of the agora not only through protests and marches (themselves public performances), but also with performative acts that bring to the public on an accessible and regular basis the ideas we’d like to transmit.

So, to get back to your question I felt both empowered by performing our ideas, and limited by the particularity of the environment (the museum) that mostly attracted an always already aware public.

The Golden Horse (OS): I agree. MMTW is about tapping into a whole different reservoir of expressivity: voice, humor, body language, choreography of our somewhat staged but for the most part, spontaneous movements. I do not think we were making such novel points, but by using an array of expressive devices, we help these ideas to ‘sink in.’

We get under the skin of our audiences.

The Hairpin (AB): Last year in Riverside there was a conference and exhibition about the MMTW at the Center for Ideas and Society at UC Riverside. The exhibition occupied three different rooms. The “Mediterranean room” included Andreea Campeanu photographs from refugee camps and a new version of “Mediterranean Sea Scroll” by Susan Ossman. When my turn came to present my work as curator of this ensemble, I became so emotional that I had difficulty speaking. Thinking about the physical and psychological abuse that migrants suffer at the hands of authority, abuse that sometimes translates in literally breaking the limbs in order to stop people from moving, I was overwhelmed. What I knew was unspeakable. Crying, on-stage or off, is usually not part of academic conferences. My inability to perform the paper as scripted was a “failure” but also a commentary on the limits of the conference genre.

It was imperative to include a moment of sorrow, of empathy, of remembrance, of awareness of our powerlessness faced with the suffering inflicted by borders.

The Golden Horse (OS): That was a powerful moment. It brings me back to your point that we need to re-evaluate and re-value the political power of the agora. How can we devise artworks in association with our research to engage the public in an accessible way? One key element for the MMTW is the way we include our own stories in our work. It’s a kind of performative, collective auto-ethnography. Another is that we tap into the material we find in specific places we travel to.

In Berlin in the upcoming MMTW workshop, we will gather at a remaining fragment of the Berlin Wall and in the Chapel of Reconciliation. The site is of a tremendous imaginative power to me. A child of the Soviet 1980s, I remember distinctly the moment the Wall came down, only, I could not wrap my head around its ‘coming down’. Because, as someone else put it, ‘everything was forever until it was no more’. And the West became accessible! But what did come next? It was like a love affair — one morning you wake up and do not know what made you love this person next to you just yesterday. This may work as a parable for the experience of many Russian-speakers, and I dare to say, other Central and Eastern Europeans too. When the physical wall went down, emotional and cognitive walls went up. What looked untenable and therefore so coveted and almost mystified, in the actual and close interaction had an effect of banal alienation. But how to convey its human particulars?

The Hairpin (AB): You remind me of Derrida’s analysis of hospitality, and on the observation that hospitality and hostility are close cousins. It is fascinating how hospitality, after a certain length of time, becomes hostility if the guest does not magically transform herself into a “same” – acquiring the qualities of the host. This is sameness in narrow terms.

I grew up in Romania, so I have similar memories from the fall of the Berlin wall. But I also remember the variety of micro-walls that immediately replaced the “big one”. Invisible and yet tangible, the “newly invited Europeans” where guests that needed to magically transform themselves into the “old Europeans” through a process called “transition” – the best exemplification of a narrow understanding of what is “sameness”. This is what happens today with migrants. The extremists label them as “radically different” and the moderates hosts ask for swift integration, failing to see the fact that we are all always already integrated in the human family. It is naive to think that nation states will leave the scene without a bloody fight. We are living it today. Neighbors, populations, cities, are all prone to clash when walls of separation project fears of what is behind, and feed into fantasies of the other radically different from “us”.

But fear also creates a space of comfort – because it keeps us in the lukewarm realm of familiarity.

A way out of our labyrinth of walls once we cozy up to fear — the Ariane’s thread that has to lead us — is compassion. Compassion not only because it is a path to healing, but also because it is a path of knowledge that there is no “otherness”. We are all connected. Care for the other is implicitly care for oneself, as care for oneself is care for the other. What we consider “the other” is our best teacher about ourselves – and this is not an anthropological ‘secret’. It is a daily occurrence – while agora is the place in which we can meet our teacher and become each other’s teachers.