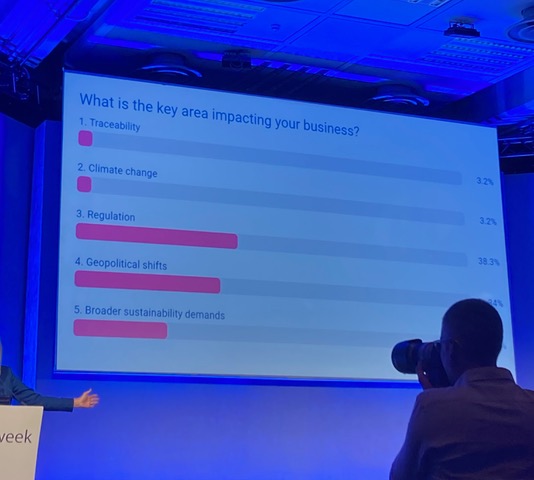

London Metal Exchange Week is Europe’s biggest annual gathering of actors in the metal sector — representatives of mining companies and smelting industries, as well as bankers, brokers, and commodity analysts. It usually takes place around the beginning of Q4 or the fourth quarter that is in October. The event sees 900 participants crowd into a venue just outside the Houses of Parliament in London. A single stage format ensures everyone follows the same talks. Their themes are “the future of metals”, “global outlook”, “investment trends”. Occasionally, a BBC journalist hired as an emcee jumps onto the stage inviting the audience to partake in polls on the conference’s themes using a smartphone app. Fittingly, as I was drafting this article, a poll in the 2024 edition asked participants about “the key area impacting your business” with suggested answers of “traceability”, “climate change”, “regulation”, “geopolitical shifts” and “broader sustainability demands”. In the final count, “regulation” won the poll. The word “regulation” is rarely a precise referent in these corners. It is more a shapeshifting spectre conjured with an exceptional vigour by the governments of the EU that haunts the companies that mine, refine, smelt, recycle and trade metals. It nudges or compels them to track and curb their environmental impacts, take responsibility for suppliers and business partners around the world, or specifies which companies to avoid altogether due to sanctions.

Regulating metals across their value chains resembles—at its best—an endless game of whack-a-mole.

Regulation is a necessary reaction to industries that are inherently damaging the environment. But it also raises the question whether it indeed protects the environment, redefines that protection along business friendly lines, or whether it is only playing catch-up with capitalism’s ability to invent new frontiers of accumulation and unchecked harm. As I listen to LME presentations and talk to the actors in the sector, I cannot help but think that regulating metals across their value chains resembles—at its best—an endless game of whack-a-mole where one of the important roles of regulation is to distribute ‘mallets’ to ever more stakeholders and to ensure that such mallets have a long reach across state borders.

LME week 2024 poll. Photo by author.

The metal sector is strategic and widely seen as indispensable. Unlike phasing out fossil fuels or limiting air travel, little has been said about limiting mining, refining, smelting or recycling. Rather, experts predict that demand for metals will grow, partially due to needs of clean energy transition and expanding digitalisation. This creates a paradoxical situation that is on full display in the 2024 report by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) introduced with the following paragraph: “mining and metals are some of the world’s most carbon-intensive sectors (…) however, the metals and mining sector has a crucial role to play in the transition to a low-carbon global economy”. Julie Livingston has coined the term “self-devouring growth” to denote a situation in which growth-oriented economic activity meets preset-day necessities whilst undermining the very conditions such as availability of water or land that make that growth possible in the long run. In recent years, governments and supranational institutions like the EU have tried to balance this contradiction by creating strategies for securing metals, on the one hand, while relying on regulation to reduce the sector’s carbon emissions and pollution, on the other.

Recently, the holy grail of these regulations […] is expanding their territorial reach ensuring that the whole metal value chains improve their standards and environmental outcomes.

The UK Critical Minerals Strategy of 2022, the EU Critical Raw Materials Act, the US Critical Minerals Security Act of 2024 — all of these call for greater domestic metal production and stronger links with business partners around the world. In parallel, these regions and their industries have adopted a range of state and corporate regulations to increase reporting, limit or trade carbon emissions, and decrease risks to the environment and bodies.

Recently, the holy grail of these regulations—especially in the EU—is expanding their territorial reach ensuring that the whole metal value chains improve their standards and environmental outcomes and not solely industries that fall directly under the countries’ jurisdictions. This is partly a representation of civil society and movement pressures that oppose the outsourcing of environmental harms. And — more importantly—it is an attempt to even the playing field for domestic companies whose operational costs have been affected by the regulation. This is put more crudely with a simple and resonant question: “How to ensure that people don’t simply end up buying cheaper metals from places with less stringent regulation?”. Regulation here is a strategic gamble—one that will increase the cost of operations but promises to bring better outcomes for the environment and social license to operate affirmed by the recruitment of young talent and the increase of financial investment. The outcome of this gamble largely depends on the ability to increase both the supply and demand for such ‘green’ solutions, especially with regards to the big metal player in the global market—China.

There are currently multiple hurdles to regulating the metal sector across the production chain. First, there is little reliable data that covers the breadth and width of the sector’s environmental impact. A recent review in Nature shows for example that half the mining operations around the world are undocumented, creating serious problems for estimating their actual carbon footprint or environmental impact. Second, the consequences of mining and processing are partially predictable but historically their impact on environments and bodies is frequently discovered only after some delay. Research points to links between metal industries and the loss of vegetation, biodiversity, food security, and increase in social conflict, air pollution and destruction of water bodies. Third, a large body of evidence shows that the metal sector makes use of resource frontiers where regulations are less stringent, which is precisely why extending the regulation is so important.

In recent years regulation, especially in the EU, has tried to address these hurdles through increasing requirements around reporting, industrial standards and sanctions, and — most controversially from the perspective of the sector—by increasing responsibility of companies for their business partners in global supply chains. The best examples of these latter motions are two recent directives adopted by the EU — Corporate Sustainability Reporting (CSRD) and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDDD). They are more demanding than their equivalents in other jurisdictions and yet they are also stripped-down versions of original drafts after intense lobbying from the private sector. Most notably, their initial implementation is limited to larger corporations operating in the common market. From 2024 onwards, these affected companies—including in the metal sector—will have to take more responsibility for their business partners around the world. The Directives address—at least on paper— what Anna Tsing (2015: 63) calls ‘salvage accumulation’ that is corporate amassing of capital while relinquishing the responsibility for the conditions under which commodities are produced. Yet, they are also different from each other in terms of philosophies and practices that they encourage.

The CSRD is a directive focused on reporting. It speaks to trust in the markets and principles of cooperation between the state and private companies. In as far as the Directive requires reporting, it relies on consumers and investors to do with the information what they see fit based on their own values or estimations of risk and opportunity. The CSRD is relatively business-friendly in that it builds on competences that companies already have as they already participate in different forms of voluntary reporting like the UN’s Global Compact, CDP survey, and Ecovadis sustainability assessment. What’s different is that the CSRD asks to report about the entire value chain which requires training business partners around the world to generate new types of data according to specific frameworks.

In comparison, the CSDDD which will be implemented in 2025-6 is trickier as it enforces a civil liability for the behaviour of large companies’ business partners around the world meaning that EU standards hold beyond its jurisdiction. The CSDDD reflects pressure from social movements. Some 700 civil society groups and trade unions alongside half a million petition signatories lobbied for the Directive to pass. To the extent that it regulates companies, the Directive has drawn critical voices. A Columbia Law School blog post penned by two professors deems it an imposition of ‘Europe’s values and political preferences on the ways business should be transacted practically in every other country…’ and undermining ‘any country’s choices on how to ensure its firms’ international competitiveness’. In a similar tone, other voices called it out for ‘rewriting the corporate law around the world from Brussels’ and undermining the ‘fiduciary duty of the board of directors’. These reactions show that what is feared about the Directive is its ability is to decrease the power of companies vis-à-vis other stakeholders in the sector (whilst increasing the power of the EU as an arbiter). Yet, the Directive’s power depends on how much of the global metal sector falls under its purview and that in turn is related to the global reach of its multinationals.

These Directives reveal regulation as a space through which people within and outside organisations are empowered to hold companies accountable and responsible for ever more variables related to their environmental and human rights record. In this context, it is crucial to see in how far these people—sustainability experts who collect new environmental data, human rights organisations who represent harmed communities, and all sorts of other actors — feel that they have a real say and how effective their ‘mallets’ are.

Having attended the LME for two years in 2023-4, alongside a number of other metals sector conferences in Europe, it is apparent that the industry is under increased scrutiny, with ever more obligations to inform the public about its environmental impacts. Reporting gives all sorts of people access to data through which they might spot suspicious patterns but it is ultimately the ability to influence operations or sanction wrongdoing that determines if the ability to witness will translate into powers of change. It is key that people who report and monitor do not feel isolated or incapacitated having to individually manage the sentiment that they are sitting on a bombshell.

Sustainability efforts are spearheaded by staff who are more female and junior.

On sustainability cultures within companies, one demographic trend is clear. Sustainability efforts are spearheaded by staff who are more female and junior. For example, the Chief Sustainability Officer at the London Metal Exchange as well as sustainability heads in top 5 metal companies in Europe — Glencore (UK), ArcelorMittal (Luxembourg), Rio Tinto (UK), Anglo American PLC (UK) and Aurubis (Germany) — are all women with between ten and twenty years in the sector. They also tend to come from social science backgrounds with masters’ degrees in gender studies, anthropology, and development studies. This is auspicious in a context in which according to a 2019 assessment of female inclusion in the sector, women represent between 3% and 29% in some 66 metal companies sampled globally. Based on my own interviews with (lower ranked but still female) sustainability officers and the reading of their comments in the public domain, many relate their work to that of ‘reporting’, ‘communication’ and improving corporate ‘reputation’ and ‘transparency’. As for the role within organisations, it is often one of ‘learning’, ‘communicating across’, and ‘bringing together different teams’. Such careful work of communication and cooperation might strike as a quality that is commonly associated with the feminine role in society. Likewise, startups that provide sustainability services to mining companies, but are not mining themselves, are made up by more junior and female teams. These are companies like CarbonChain, which develops measurement and reporting products, or Sirus, which offers AI models to help sustainability officers respond to sustainability related queries from business partners.

Sustainability experts are unsupported to change corporate behaviour, leaving them not only stressed about the constantly changing regulation but feeling isolated.

A focus solely on reporting means that sustainability officers can feel like their importance in organisations is limited. A recent Reuters article—shared at a metals sector conference by a representative of one of the sustainability data start-ups to an audience of a panel about sustainability reporting—asks ‘has burnout made the role of the chief sustainability officer unsustainable?’. The article suggests that that poorly defined but ever-expanding reporting targets lead to overwork. It diagnoses that sustainability experts are unsupported to change corporate behaviour, leaving them not only stressed about the constantly changing regulation but feeling isolated. The conclusion of the article is that sustainability officers have been in a ‘culturally weak’ position.

The implementation of the CSDDD will give another indication if the position of sustainability officers has been strengthened or not as there is a potential of actual civil liability for big companies for the behaviour of their business partners around the world. It remains to be seen how many cases come to the court and how they are treated once they get there. Already the Directive has come under criticism from the movements due to last-minute changes that reduce the number of companies affected by the regulation, mostly meaning that only largest companies now fall under its purview.

One of the important roles of regulation in a sector that is both economically powerful and environmentally hazardous is to ensure that economic actors are responsible and accountable to ever more people whose ‘mallet’ to smack them down for harmful actions reaches wide and far. In this sense, regulation is about creating a relationship between a wide variety of stakeholders who are empowered to take action as harms occur. This inevitably gets us to the question of cultures and social life of regulation as regulation depends both on state action towards these companies but also on stakeholders’ reaction to regulation. Yet the metal sector ultimately reveals regulation’s limitations. As I listen to conference panels, the balancing act that regulation does between responding to industrial needs and compelling greater responsibility gets a buy-in from corporations because they hope that costs associated with responsibility can be paid for by greater financial returns. Regulation’s own ‘license to regulate’ hinges on corporate growth, which is in itself the root cause of environmental harm the regulation purports to address. Importantly, corporate growth occurs in the context of global competition, and should EU companies feel ‘stifled’ by regulatory costs that their competitors in China or the US are not, we will soon find out what is more important: the environment that sustains life or corporate profits that sustain GDP.

Featured image: Photo by Gisa Weszkalnys

Bibliography

Livingston, J. (2019). Self-Devouring Growth: A Planetary Parable as Told from Southern Africa. Durham: Duke University Press.

Tsing, A.L. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Abstract: Metal sector regulation attempts to balance industrial needs with environmental and social responsibility. Through ethnographic observation of the London Metal Exchange Week and analysis of recent EU directives, this article argues that to improve this balancing act regulation’s role is not solely to increase the state’s ability to intervene in the private sector but also to empower ever more people to hold companies accountable. In that regard, the crucial feature of regulation is how far it empowers individuals to challenge the corporate power and shape its operations. To illustrate this, the article focuses on recent EU directives, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD): one compels corporations to ensure better reporting, while the other makes them legally liable for the conduct of their suppliers around the world. I show that the effectiveness of reporting remains contested, as corporate sustainability officers responsible for the process often feel isolated and limited in their ability to influence change. In comparison, increasing legal liability for corporate wrongdoing around the world that promises greater ability to push for corporate change but also generates more private sector opposition. Regulation of the metal sector is emblematic for the challenges of regulation’s balancing of economic and societal imperatives: it is based on the assumption that higher regulatory costs will be offset by greater financial returns. As such, regulators’ ‘license to regulate’ hinges on growth-based model of the economy which is forever threatened by global competition.