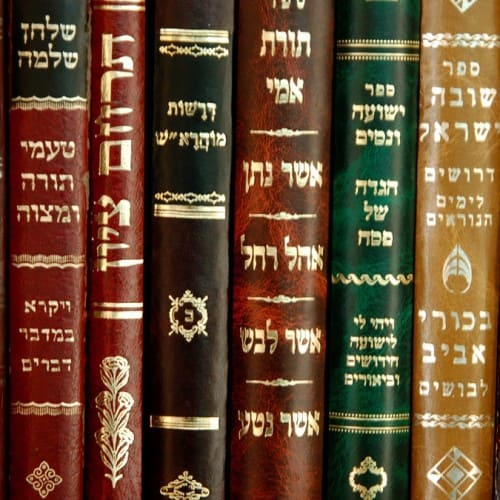

Gish Amit is a historian who has been involved in non formal education for twenty years. He taught cinema and literature at the Arab Democratic School in Jaffa, and lectured in philosophy and critical theory at Tel-Aviv University and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Amit’s book Ex-Libris: Chronicles of Theft, Preservation, and Appropriating at the Jewish National Library just came out (in Hebrew) with The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute last year, and in Arabic with Madar, the Palestinian Forum for Israeli Studies, Ramallah. The book tells the story of three events that took place within the Jewish National Library: The “Diaspora Treasures” project, which after World War II brought to Jerusalem hundreds of thousands of books owned by Jews that had been looted by the Nazis; the collection during the 1948 war of 30,000 books that were owned by Palestinians; and the gathering of books and manuscripts from Yemenite Jews who arrived in Israel at the end of the 1940s and the beginning of the 1950s. In the context of our thematic week on AAA, BDS and #Palestine, Allegra sat down with him for a virtual conversation on the cultural aspects of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Julie: We, at Allegra, are delighted to be able to feature your work, especially because your book has not been translated into English yet (and we hope it eventually will). Before we discuss its content in greater details, could you tell us a bit more about the reasons for which you became interested in researching the National Library? Why, in your view, is it an interesting site from which to unpack the current Israel-Palestine conflict?

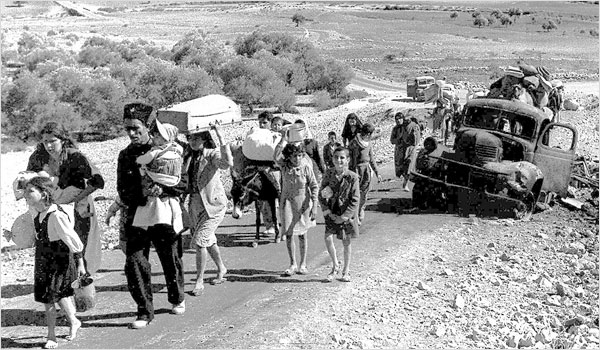

Gish: Thank you, Julie. The starting point of my research was an unsettled feeling that though the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been discussed and analysed from many perspectives – the refugee problem, the consequences of the war, etc., there is one crucial aspect that gained very little attention – namely, the cultural aspect of the conflict. From this point of view, we should be aware of the fact that the struggle between the Zionist movement and the Palestinian people was not only over territory and self-determination, but over memory itself, which is strongly connected to the question of culture. As soon as I realized this, it became clear that I wanted to reveal the unknown story of the ways by which Zionism succeeded in claiming not only the land, but also its pre-Zionist history.

And yet there was another issue that deeply influenced my work – as you probably know, there is a common distinction between military power and cultural institutions, as if culture is separated from the realm of political violence. Even though we know very well how futile and dubious this distinction is, I believe it still has a strong holding in our life and ideology.

Judith Butler, building on the work of Raymond Williams, Theodor Adorno and Michel Foucault, defines critique as a way of « disclosing spaces that are secluded from us ». One would not automatically think of the National Library as such a space, precisely because it is a ‘public’ space, theoretically opened to everyone…

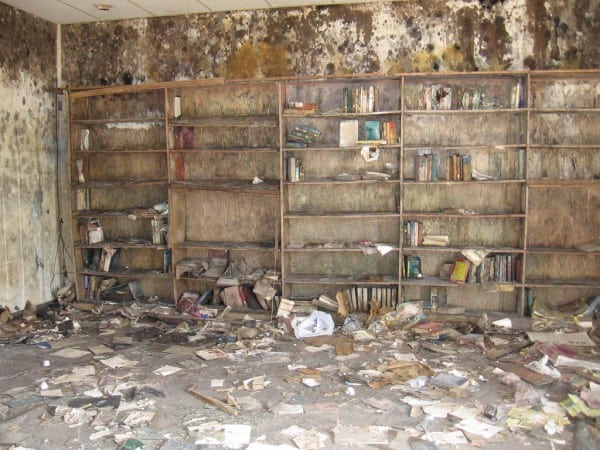

Yes, it’s true. As I already mentioned, the national library is not the first space that comes to mind when we think of political theory and past wrongs. But this is precisely why this place is so critical to the very process of acknowledgement and reconciliation, since it preserves, within its walls, the traces of cultures and memories that had been buried and repressed; these traces, these books, not only of Palestinians but also of Yemenite Jews and Holocaust survivors, have been waiting in the library for so long, waiting in this liminal position: they are an inseparable part of the past, and yet an essential element of any future process of recognition and forgiveness – however unimaginable this process may seem to be in these horrible days.

Your book has made quite a lot of noise in the press since it came out last year. It seems to reveal a story that very few people in Israel and in the world more largely are aware of. Why, in your view, revealing these interweaved stories has been so controversial ?

It’s true. The book has made quite a lot of noise. I can think of three reasons: first, very few Palestinians, not to mention Israelis, knew anything about the Palestinian books that had been collected or looted by the national library during the 1948 war, and there are not, of course, too many Jewish Israelis who are willing to discuss the event, as well asthe other events that constitute my book, in the context of plunder and injustice. For the great majority of Israel’s public opinion, if at all, these episodes should be discussed only from a perspective of grace and salvation (this does not mean, by the way, that aspects of rescuing were not part of these events. As a matter of fact, what interested me most was a kind of ambiguity, combination of plunder and preservation that prevail these three events).

It’s true. The book has made quite a lot of noise. I can think of three reasons: first, very few Palestinians, not to mention Israelis, knew anything about the Palestinian books that had been collected or looted by the national library during the 1948 war, and there are not, of course, too many Jewish Israelis who are willing to discuss the event, as well asthe other events that constitute my book, in the context of plunder and injustice. For the great majority of Israel’s public opinion, if at all, these episodes should be discussed only from a perspective of grace and salvation (this does not mean, by the way, that aspects of rescuing were not part of these events. As a matter of fact, what interested me most was a kind of ambiguity, combination of plunder and preservation that prevail these three events).

Second, most liberal Israelis still hold an illusion that culture is not part of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and many of them have a strong sentiment toward the national library, which apparently represents and symbolises the noble of Israel. It is simply too hard to admit that the national library and the Hebrew University played an important role in the process of conquering the land and the concealment of the Palestinian history.

And finally, it’s worth mentioning that even today it is almost impossible in Israel, to think about the Holocaust and the Nakba as historical events that are related to each other. As a matter of fact, in a period of national radicalization and aggravated racism, it becomes even more difficult. However, this is precisely what my book tries to do, to think about the denied connections between these two catastrophes, without, of course, ignoring the fundamental and principle differences.

Your work highlights an aspect of the conflict that is rarely considered by historians who specialise on the region, namely the complex link between literature and sociopolitical violence. Why, in your view, is culture a central ‘battleground’ in the specific context of the Israel-Palestine conflict?

In addition to what I already said, my work argues that these three events are deeply intertwined in the way they reveal the manner by which Zionism has separated between people and their culture and heritage as part of the formation of national identity. I try to paint a new portrait of the National Library: not a site of secluded history, which is permanently decided and determined, but rather a continuous present tangled up with its own past — a space of injustice that also enables processes such as reparation, recognition and forgiveness; a vulnerable fragile space that carries the memory of disaster, that preserves the traces of disaster and its remains. A site that subverts the concept of past and gives the past lively, unsealed dimensions; a space that isn’t a past, but rather, in Jacques Derrida’s words: “an answer, promise, and responsibility toward the future.”

Your book discusses an important episode in the making of the Israeli state, namely the ‘nakba’ (the ‘day of catastrophe’), or the massive exodus and displacement of Palestinians which preceded and followed the independence of Israel in 1948. This displacement was accompanied by the systematic collection of Palestinian cultural assets. But there seems to be an ambiguity here: were these precious books and manuscripts collected for preservation purposes or were they simply stolen? Is there even such a simple way to describe this event and its intended and unintended outcomes?

For me, what makes these events so peculiar is the fact that it makes any kind of clear distinction between appropriation and preservation impossible. Contrary to such differentiation, I try to show how these two aspects always function hand in hand, in order to shape a complex duality. In this regard, we should remember that all three episodes were described by their perpetrators in terms of grace and salvation. At the same time, each of the affairs was meant to establish the identity of Jerusalem intellectuals who were involved in the events– among them Gershom Schole, Martin Buber and Yehouda Leib Magnes – as Western, while helping them escape the embarrassment they experienced as a result of the images of the European Christianity and Orientalism. And in all three affairs, intellectuals and bureaucrats whom acted out of a commitment — complex as it was — to the Zionist project had taken the right of representation from those who could not speak up or were denied of representation in history. This all happened within the walls of the National library.

There seems to be no end in sight in this conflict which has been going on for almost 60 years now. But in spite of the little hope that media reports leave us with, your book opens up a space for thinking creatively about recognition, correction and forgiveness…

History has known moments of reconciliation, even between bitter rivals. Yes, there seems to be no end in sight, but Israelis and Palestinians are living together on the same land, and therefore we cannot give up hope. And there is one more thing – if, as I believe, recognition is the first step towards forgiveness, then the library, being a site of so many symbolic significances, is a great place to begin.

Featured image by chany crystal, CC BY-ND 2.0.