Is it for a lack of knowledge? The genocide in Gaza is being livestreamed. Daily, images, videos and voice notes proliferate faster than they can be witnessed or heard or known. We have numbers, data visualizations, graphs and charts of death tolls and aid trucks and calorie counts. And we have histories, recent and canonical. And of course, human rights violation reports, health analyses, compendiums of laws. We have transcripts of government officials calling for Gaza to be flattened, leveled, made uninhabitable. We have seen these calls realized every day.

And we also know that the institutions to which we belong, through which we make our living, our art, and our work, are actively investing in making Gaza unlivable. They are invested in apartheid, in war, and in the dispossession of Palestinians. We know that “decolonizing” is not an abstract idea that we use in the titles of our syllabi but is in fact a verb. To add to it all, we are witnessing our students, the undergraduates that we teach and mentor, being targeted by universities for their activism, arrested and harassed by the very institutions that purport to be bastions of learning and freedom of speech.

It is worth asking then, what are the ethical demands that knowing makes on us? This is the problem that we grapple with as we write this text, and it is the problem for which we will certainly not present an answer, but perhaps some initial lines of thought.

To answer this question, we must dispense with the notion of knowledge as a pursuit unto itself and the raison d’être of the university. We must see the university as it is, not as it imagines itself to be. We cannot see ourselves as innocent citizens of a university system which actively participates in violence. The university is not an epiphenomenal structure; we are part and parcel of it. And we must acknowledge our role in the material structures and systems that make up the university.

And we know that the institutions to which we belong, through which we make our living, our art, and our work, are actively investing in making Gaza unlivable.

Therefore, we must first confront a clear condition of contemporary academic life: the American university system invests heavily in futures, and these futures (both in the financial and temporal senses) rely on past and ongoing injustices to propel projected growth. As we argue later, university financial regimes prefigure injustices such as the Israeli occupation of Palestine as grounds for speculation and options trading. Such practices are not new; universities in the United States and across the pond, in United Kingdom, held considerable investments in companies involved in the Atlantic slave trade and in companies that supported the apartheid government of South Africa. In the United States, many universities have a history of investment in private prisons. While these practices are not new, universities’ involvement in futures speculation has dramatically intensified.

Futures, in a financial sense, are contracts wherein the value of an asset is based on a predetermined price on a future date, such that additional value is generated by exploiting the speculative difference between present and future prices (Miyazaki 2013, Meister 2021). In this sense, futures revolve around the “creation of difference” (Miyazaki 2013). Financial futures work as virtual realities which are then actualized. But these financial technologies are also creative, narrative technologies, populating the past and future with “counterfactual economic imaginaries,” thus establishing capitalist growth as a necessary precondition for present day experience (Beckert 2016). Modern financial imaginaries of the future rely on past valuations, knowledge which sets expectations for the future.

Our universities invest in these futures, but they also generate the knowledge which is used to imagine–and actualize–these futures, futures which do not include a free Palestine. Today’s university students, faculty, and administration, although they occupy different roles within the university, are increasingly implicated in institutions that do not prioritize education but rather function as hedge funds, siphoning tuition dollars and donations into areas such as military weapons manufacturing and energy extraction. From within this context, arresting student protesters can be seen as part of an institutional strategy that consists in protecting Universities’ investments (Members, forthcoming). Recognizing this, it is imperative, then, that we reconceptualize the very imbrication of knowledge, in/justice, and futures in university spaces from this starting point.

Scholars like Robert Meister and Clifford Ando have researched university financial practices since the early 2000s and have come to interesting questions about their operations. Their reports on the University of California and University of Chicago systems respectively indicate how university budgets have seen large-scale cuts to student education (vacant professorships, the elimination of seminar courses etc.) and a dramatic increase in tuition charges. Newly generated funds are then injected into private investments. Although these investments are not openly discussed, housing development, defense contractors and energy companies frequently appear within university portfolios.

In addition to these financial investments, universities like the University of Chicago directly partner with Israeli institutions on future-facing development projects ranging from security technology to water purification infrastructure. UChicago’s engineering schools, in partnership with Israeli universities and American national labs and federal institutions, fabricate materials to remove water contaminants and develop technologies to desalinate water. This is particularly nefarious considering Israel’s current blockade on clean water to Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. Israel has historically weaponized its water infrastructure to control aquifers underneath Palestinian territory and prevent Palestinians from collecting rainwater. It also actively destroys existing water infrastructure, most recently as it escalated its siege on Gaza and planned to flood tunnels with sea water, potentially contaminating groundwater for generations to come. Knowledge production in this partnership fails to address how its innovative solutions are used to create dire conditions of scarcity in Gaza and the West Bank (Doostdar, talk 2023).

As the genocide continues, universities continue to hold massive investments in this global financial scenario. Not only are universities tied to such present violence, but they also actively trade in financial futures that necessitate Israeli occupation, military operations, land development, and energy extraction for their profit.

In his recent book Justice is an Option, Robert Meister connects today’s financial futures trading with a temporal relationship to injustice through the concept of “optionality.” Options trading, the hedging of speculation on future financial outcomes, occurs through the management of investment portfolios and the purchase of movement between those financial futures (Meister 2021, 8). Today’s trade in options is made possible through a relegation of historical injustices into abeyance. Past and ongoing injustices, such as the settler-colonial displacement of Palestinians, and Israel’s formation as an apartheid state, are made into necessary preconditions for present-day financial possibilities for investment in gas drilling or water infrastructure. In essence, university investments hold “counterfactual power” over the past and a dependency of the future on a present “in which we remain free to choose based on our prediction of what the future will be without therefore believing that we can change it” (Meister 2021, 80). Universities rush to push things like Israel’s occupation of Gaza to the near past to justify their financial predictions.

As the genocide in Gaza continues unabated, the knowledge materialized in our university spaces feels both prolific and inert to stop it.

And so, what does this mean for the veneer of knowledge production that universities continue to define themselves by? In a world where universities act as hedge funds, students and faculty are made into clients of such futures. Knowledge production at universities orients itself in relation to institutions’ investments in these same futures, whether it is in the direct form of engineering projects like UChicago’s partnership with Israel’s water purification program, or in less apparent pathways like through the humanities. Indeed, the formation of area studies programs, in particular after World War II, have blurred the line between university and state interests. Today, many humanities programs that discuss the “Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” or “Modern Middle East History,” function to legitimize American foreign policy (Chow 2006, Khosrowjah 2011). Within such programs, Israel’s ongoing campaign of extermination becomes shaded with a sense of humanitarian inevitability, a post-hoc justification for what is pushed behind as “near east history.”

But when the dire problem of Israeli occupation emerges again and again, and scholars of a wide variety of disciplines must face it, scholarship suddenly feels “stuck.” What kind of knowledge is a knowledge that feels stuck in the present (Scott 2014) between the violence of a past that is supposedly past and a future that requires investment on behalf of this past? Academics of every variety confront the real pressure that the fulfillment of university investments means a fulfillment of their own investment in the university – for jobs, stability, and above all, “optionality.” And they are faced with the perniciously tempting desire to “see it play out,” and then, in the case of some, theorize about such violence in the past tense. If university finances secure themselves by locking-in a present condition (Meister 2021, 2) and anticipating the future’s valuable accumulation from ongoing atrocities – such as in Gaza, then university personnel often find themselves feeling similarly locked-in. In the case of researching and teaching about ongoing genocide in Palestine, these university affiliates are trained to lie-in waiting for that moment when violence has supposedly ceased, and researchers can safely discuss the retrospective innocence of victims and the culpability of perpetrators (Meister 2012). This is a politics that delays justice while benefiting from the proceeds accumulated in that delay.

As the genocide in Gaza continues unabated, the knowledge materialized in our university spaces feels both prolific and inert to stop it. Such knowledge is so truncated that it ceases to be experienced as a form of knowing but instead feels dispersed and impoverished. The knowledge produced at universities has degraded into mere information, characters and pixels lacking any conviction. Information here has no moral or political impetus. In the present, it has no force. This disfigured kind of knowledge can only produce a radical politics in retrospect, as part of an archive that can no longer incriminate us. We can know only as historians, nestled safely in the aftermath of established facts and accomplished history, unclouded by the complex and sensitive exigencies of an unfolding catastrophe.

So, we linger in abeyance, letting information wash over us, unprocessed, ineloquent. For once information takes a form, it makes demands upon us. Once bits of information are given names and attributions, once they coalesce into a structure, they become knowledge. As knowledge-makers, this is precisely what we are called upon to do, and yet we seem to have embraced an informational approach to knowledge. One in which facts are commensurable, exchangeable, and neutral, stuck in epistemic purgatory, under-articulated and yet to be known. As Palestinian human rights attorney Rabea Eghbariah wrote in an essay that the Harvard Law Review refused to run, “does one have to wait for a genocide to be successfully completed to name it? This logic contributes to the politics of denial” (Eghbariah 2023).

For if knowledge stands apart from us, abstracted and reified, it too is emptied of its moral and political character.

By conceding any power our work may have to disrupt ongoing violence, we precisely manifest this politics of denial. Now more than ever, we must resist the temptation to indulge in the aesthetics of erudition and learning, confident in the nobility of our epistemic labor–conceived of as separate from our political labor. We already have a surfeit of knowledge, and yet we are stuck. Perhaps we must admit that while there is knowledge, including knowledge that we ourselves produce, we have declined to know. For if knowledge stands apart from us, abstracted and reified, it too is emptied of its moral and political character, degraded into pseudo-knowledge, acting as a corpus of information-plus, which says nothing and does nothing.

As scholars and students, it is we who provide the universities-as-hedge funds with the legitimacy necessary to claim themselves as places of higher learning, and it is through our relationship with the university that we emerge legibly as faculty and students. The university structures and regulates our relationships to one another as well as to available resources. And so, we are implicated in the very activities of the university-as-hedge fund. This relationship is not one that we can inhabit passively. Confronting this reality requires our vigilance, but also our dissent and refusal and an acknowledgement that though we might be at odds with our universities, we are still a constitutive part of them. We must ask, “where are we? And who are we in the university where apparently we are? What do we represent? Whom do we represent? Are we responsible? For what and to whom?” (Derrida 1980).

We are responsible to inhabit our institutions such that we are not clients and in which our knowledge production, teaching, and learning, are not predicated on investments in unjust futures. Or else we are responsible to refuse the university altogether.

From the starting point of understanding the university’s role in contemporary financial accumulation upon past injustice, we argue for a redefined ethical disposition among university affiliates. This ethico-political form challenges today’s vacillation among many academics between a presumed responsibility to maintain intellectual production, and the atomization (indeed alienation) of “colleagues” in the deconstruction of their responsibility to the university (Derrida 1980). Both of these approaches fail to address the weaponized form of investment which the university today embodies. Instead, we acknowledge that radical traditions of Black, Indigenous, and colonized people within universities have long operated, indeed labored, to cultivate “another side,” a collective orientation to a different kind of knowledge and thus a different kind of future (Moten and Harney 2013: 26-27). Indeed, one in which “the generation of knowledge in the university—at the level of its form, content and practices—tends towards the knowing degeneration, disorganization and disequilibrium of the university” (Moten and Harney 2020: 3). This is not some absolute responsibility to, or even through, the university, but a shared responsibility toward one another and ‘others’ in spite of the invested future the university participates in.

Our dissent and refusal of business as usual are tools in refashioning this inhabitance. Our critique and dissent must also set the terms against which we are constructing our critiques – as scholars, and artists embedded within universities across the country, it behooves us to collectively reimagine being in the university. What does it mean for us to participate in the institution of the university? How shall we be scholars and teachers in universities? What does it mean for us to produce art or knowledge or music from within these institutions? Or better yet, as Moten and Harney (2020) ask “How do we keep work from rising to the status of ‘the work’ or, higher still, ‘my work’?”(1). “What does it mean to work against the institution you work for when your working against the institution is extracted by the institution as surplus?” (ibid, 5). How can we cultivate spaces within the university in which we share stakes with a world beyond our campuses? What does it mean for our labor to be predicated on investments whose harm spans geographies? What kinds of literal investments are we making and in what futures? The questions to be asked are endless.

We must create spaces in which refusal of the university-as-hedge fund is not only possible, but necessary.

To critique the university as a space and as a structure cannot only be an endeavor to expose its flaws and injustices as we see them, but it must also be an effort to reimagine the spaces that can be forged despite the university, and in which liberatory politics and solidarity with a world that lies outside is possible, and in which we can move beyond the institutions of the scholar, professor, and artist, in the interest of shared experience and shared projects (Moten and Harney, 2020). The ivory tower must be sullied because it was never pure to begin with. We must unsettle any notion that our intellectual and artistic pursuits are separate from and unresponsive to the very conditions of their possibility.

We must create spaces in which refusal of the university-as-hedge fund is not only possible, but necessary. Even while we might inhabit a relationship of antagonism toward the university, our sense of our own complicity is incomplete without a reckoning with the material basis that is the condition of possibility of our own work and the effect it has on people who lie far outside the borders of our campuses. We must refuse our isolation and atomization and that of undergraduates, as well as the depoliticization and instrumentalization of our intellectual and teaching practices. We must insist that we owe something to one another, and to the people whose lives, contexts and histories line the pages of our volumes and source the inspiration for our art. We are responsible to and must insist that we respond to people whose lives are affected by the activities of the university, which are the same activities that enable our scholarship.

We must divest epistemically and materially from colonial violence and unlearn the fiction that these were ever separable in the first place; and we must demand that our universities divest from futures that shore up Israeli apartheid and enable genocide.

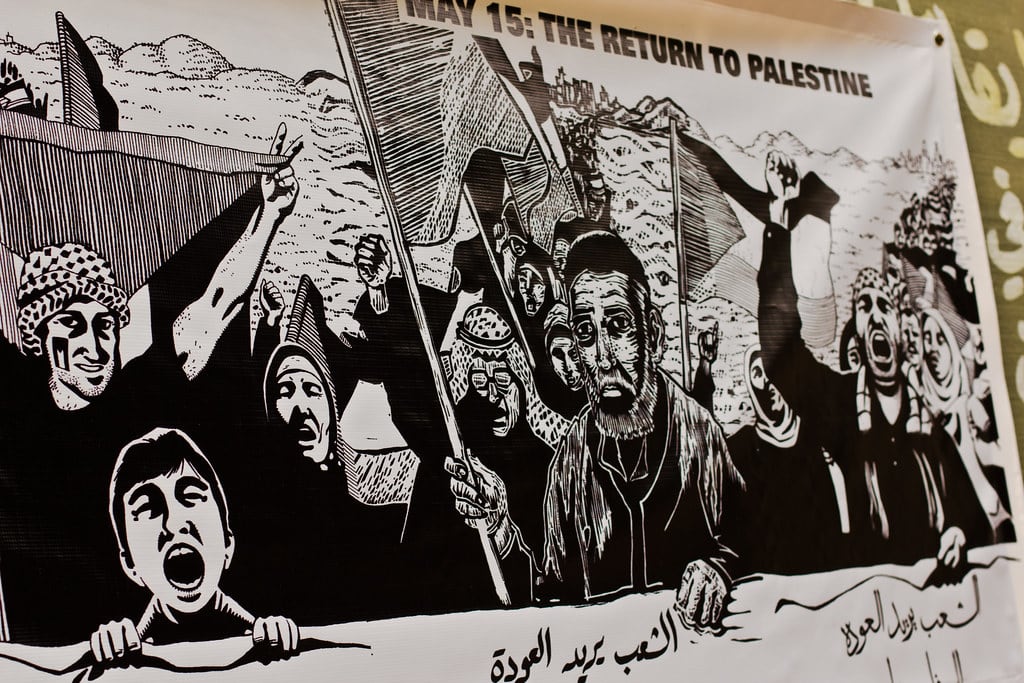

We must stand firm with a free Palestine.

Sources

Doostdar, Alireza. 2023. “Critical Perspectives on the Crisis in Gaza.” The University of Chicago, October 19.

Beckert, Jens. 2016. Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations and Capitalist Dynamics. Harvard University Press.

Chow, Rey. 2006. The Age of the World Target: Self-Referentiality in War, Theory, and Comparative Work. Next Wave Provocations. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 2004 (1980). “Mochlos, or The Conflict of the Faculties.” In Eyes of the University: Right to Philosophy 2, translated by Jan Plug, 1st edition, 83–112. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

Eghbariah, Rabea. 2023. “The ‘Harvard Law Review’ Refused to Run This Piece About Genocide in Gaza,” November 22, 2023. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/harvard-law-review-gaza-israel-genocide/.

Khosrowjah, Hossein. 2011. “A Brief History of Area Studies and International Studies.” Arab Studies Quarterly 33 (3/4): 131–42.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. 2013. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. New York, NY: Minor Compositions.

———. 2020. The University (last words).

Meister, Robert. 2012. After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

———. 2021. Justice Is an Option: A Democratic Theory of Finance for the Twenty-First Century. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Members of Uchicago United for Palestine. 2023 (December 20). “UChicago Arrests Students to Protect Investments in Israel.” The Triibe.

Miyazaki, Hirokazu. 2013. Arbitraging Japan: Dreams of Capitalism at the End of Finance. Berkeley: University of California press.

Said, Edward W. 1996. Representations of the Intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures. Vintage.

Scott, David. 2014. Omens of Adversity: Tragedy, Time, Memory, Justice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.