“Obviously, a school that makes active children sit at desks studying mostly useless subjects is a bad school. It is a good school only for those uncreative citizens who want docile, uncreative children who will fit into a civilization whose standard of success is money.” (A.S. Neill 1960, 8)

Experimental object? Arguably, this is what children and students are becoming under the new pedagogy of financiation. It demands better “results” in less time with fewer teachers in less schools and universities. Complicating the existing well-working education system makes no sense, but it is happening. For example, in Finland – a small country proud of its excellent schools and learning results – about one billion euro has been cut from the education system during the last years. When pedagogy is increasingly based on individual recourses and motivation rather than on democratic and open learning, schools stand a danger of becoming sites for the production of ultra-individualistic personalities. If education will encourage self-interest in young people, they might grow up with a difficulty to attach any positive value on meritocracy.

Therefore, it is highly legitimate to ask if gross savings in education investment will result in increasing injustice in our society, in creating stricter boundaries between what is deemed as successful and non-successful personal lives. My case study here will be Finland, a liberal and democratic country which maybe has had little impact at the level of global politics but which has invested in education as a national strategy; a country previously proud of its leading PISA results trembling now at the fringe of “confused Scandinavia”, as The Guardian recently put it. Finland is a good example of the democratic Nordic education systems, but it is also a unique case as it is facing a rapid demolition of its education system at the hands of right-wing liberal politicians supporting international businesses cashing in on the national economics of a very small welfare state.

The liberal ideal of people as individuals looking out for their own personal good, a strong motivation in British and US education, does not fully match with Nordic pedagogy ideologies which developed in the course of profound socio-political discussions in the 19th and early 20th centuries. There was always space for the utopian in the Nordic education sphere, especially at times of larger societal changes. While Nordic countries each have their own pedagogical histories, complexes of many contingent traditions, the comprehensive school that offers 10 years obligatory, free of charge education for all children was one shared major utopia materialised.

Ideals of alternative education and “free school” (a non-profit-making, independent but state-funded school which is free to attend but which is not controlled by a local authority) were also circulated and localized in Nordic countries. For example, the Summerhill School offered some testing ground ideas for the developing comprehensive school in the late 1960s Finland.

It seems likely that the current stress on individualism will again be prompting some radical resistance in the education sphere (in Finland, a movement campaigning for the establishment of an alternative school has become active during the last few years, and an online home school has already been established, an experiment drawing partly on Summerhillian ideals). Here, a relevant question for experts in legal anthropology is to ask if the emerging alternative schools, in attempting to divert their curriculum from the state schools, could avoid being dovetailed with neoliberalism’s interest in encouraging individual “choice”. This question touches not only the relations between the individual and the culture but also those between social movements and the state, as utopian sites always have a complex and complicated relationship to mainstream culture and its norms.

It is thus time to think about past struggles and alternatives for education in order to imagine what kind of young people do utopian educational places may potentially produce. To frame my discussion, I will first cast a brief look at the history of the Summerhill School, since its revolutionary education ideas continue to impact alternative pedagogies in many countries. In the current ear of individualism and self-gain, it is of particular interest to investigate how Summerhillian sites, which stress both the particularity of each child and the autonomous nature of children’s’ own communities, actually affect the self-images of children. In the second part, I will look at the history of education in Finland, because it will help to contextualise the embeddedness of individual experiences in the wider education culture. This theme will be studied in the third section, which looks at the implications of one’s own childhood history in experimental pedagogy in terms of construction of the self.

Self-regulation as the basis for an alternative system of justice

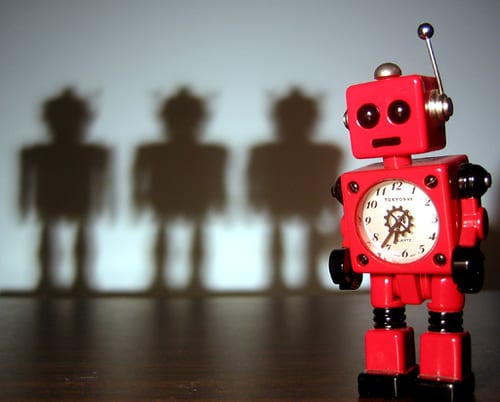

The ideologist behind Summerhill is A.S. Neill (1883 –1973), a Scottish educator and author. Neill started his first experimental progressive school in Germany in the early 1920s. Many of the pupils of this Hellerau School were Jewish children who later, tragically, ended up in concentration camps. After Nazism started to gain ground, Neill moved to the UK where he opened the Summerhill School in 1923. After nine decades, the school still operates according to his principles with about 80 pupils, many from abroad, now under the supervision of Neill’s daughter Zoe Readhead. Summerhill is equally famous for its philosophies of freedom from adult coercion and for its community of self-governance. Neill himself believed that the function of children is to live their own life, not the life that anxious parents and other adults think they should live or one governed by the purpose of educators who think they know what is best for children. Interference and guidance on the part of adults only produces a generation of robots, Neill thought.

Nowadays, Summerhill is the most famous concrete utopian site for independent education in the world. This is reflected both in how Summerhill has negotiated its existence with the dominant order in the UK and how it has inspired alternative education outside of England. It has faced continual disapproval on the part of British authorities, particularly with regards the practice that children should not be forced to attend classes, a practice that does not fit with the dominant education ideology’s stress on obligations. Further, the tradition of the School encouraging children to explore their own sexuality as well as the practices of touching between adults and children has raised moral suspicion, in particular since the discourse on child sexual abuse has gained ground in the UK since mid-1990s. Accordingly, in 1999, the British Government ran an inspection of the school, which resulted in a number of complaints being formally brought against it. Summerhill appealed against the findings and won their case, with only minor changes having to be made – a result which gained wide support from the educational community around the world. The government proposed a compromise settlement, and the school asked for time to consider it, subsequently holding a school meeting in the courtroom to determine collectively whether to accept it. The High Court proceedings were stopped and government officials were forced to wait while a group of school children held a vote to decide whether or not to accept their proposal, as Davina Cooper describes the event in her book Everyday Utopias (2014).

Then again, what makes Summerhill unique is precisely the fact that it is based on the principle of children’s self-regulation. The community makes rules by voting in school meetings. Disputes are brought up and discipline decided upon out in the open, with the pupils – along with the staff – deciding on a punishment that fits the ‘crime’.

Everyone, staff or pupil, has an equal vote. As these meetings serve as both a legislative and judicial body, they form an alternative system of justice, as appeals are possible at the end of the meeting. According to Neill (1960, 21), “no culprit at Summerhill ever shows any signs of defiance or hatred of the authority of his community” since they all have an instrumental part in creating and sustaining it.

Neill was also assured about the importance of individual possession. This idea follows, at first glance, the liberal ideal of the benefits of private property as the basis on which one learns to take responsibility. Summerhill, however, as a practical utopian site, has attached the value of property to community and belonging in ways that stretch it “beyond the subject-object relationship to encompass other kinds of institutionalized belonging”, argues Davina Cooper (2014). In this way, school property boundaries are brought into sharper definition, which again affects both positive and negative external perceptions of Summerhill, because it does not follow the prevailing norm of private and public property, or private owning.

At Summerhill, the laws of an external authority are elided in favour of the authority and self-made laws of a democratic community. Summerhill children are apparently quite conscious of the contradictory response from their immediate environment and wider society, but at the same time, they are highly protective of their school, notes Cooper (2014). Neill himself believed that “free children are not easily influenced; the absence of fear is the finest thing that can happen to a child”. It has been claimed that, consequently, adults who spent their childhoods at Summerhill (theoretically) have an integrated and secure identity that is not easily open to outside threats and neuroses. Gorman (2014) argues: “The natural rebellion against the ‘father’ that codifies the Symbolic Order is partially avoided as well – there is no ‘father’ at Summerhill to answer to”.

Neill’s thinking on child as free was revolutionary, but also closely tied to liberal ideas which are conjoined and consolidated by the British tradition of interest politics: groups of individuals positing a free will uniting to protect their shared interests and rights against the authoritarian state. Hence, there is also a strong stress on the concepts of rights and freedom in Summerhill ideology. Neill followed Rousseau in seeing the doctrine of “original sin” as a means of control.

This thought invokes Rousseau’s idea of children being born innocent and good, tabula rasa, with society corrupting them and making them miserable and cruel. Neill was also deeply influenced by Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Reich – one of the most radical members of the second generation of psychoanalysts after Freud and the author of the renowned analysis of fascism’s mass psychology – in his belief that children should not be denied sexuality: otherwise they would inherit adult fears. The core idea of Summerhill was ‘release’: “Allowing a child to live out his natural instincts”. Neill believed in self-examination and often invoked the concept of “self-regulation”, adopted from Reich (1930; 1931), who famously defended the right of youth to genital satisfaction, suggesting that all behavior should come from the natural self of the child.

I will now briefly frame the history of education in Finland in order to contextualise the arrival of A.S. Neill’s ideas to the education sphere in the country. After this exploration, in the last section of the essay, I will again return to the question self-construction in a Summerhillian utopia through actual experience.

Does the Child Belong to Itself – or to the State

Generally, Finnish culture and academic society were strongly influenced by German literature and philosophy until the mid-20th century. What is often forgotten is that Rousseau heavily affected the conditioning of German education culture in the late-18th and early-19th centuries, probably even more than neighbouring France, as Paulsen (1918) notes. Accordingly, in Finland, the education discourse was deeply affected by the German idealistic tradition, which again was heavily engaged in a complex dialogue with ideas originating in liberal traditions in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. It was therefore influenced by both Rousseau’s and Hegel’s thought in terms of the aim of education and the idea of the child.

The ideology of comprehensive schooling was first debated in Finland in the late-19th century, when two principal ideas about the content of this new concept were in competition. The first line of thought underlined the concept of Sittlichkeit, originating in Hegel’s philosophy. It refers – roughly put – to the habits of the nation combined with the political courage to make judgment when needed. The Finnish national philosopher, J.V. Snellman, was the advocate of this line. For him, education was never universal but always aimed at raising a specific historical person – Finnish, female, agrarian, or something else. He saw the child as a future member of society and the state. Therefore, the child needed to be educated to understanding fully what the membership of the state means and requires. (It is worth pointing out that Snellman, who is usually seen as Hegel’s interpreter and translator in Finland, also refers to Rousseau in his major works.) The second line of thought stressed positivism, science and innovation. It was promoted by Uno Cygnaeus. For him, the origin of education sprang from the Nature itself, and its target was to develop and cultivate the personal internal ethics of each singular pupil. This latter view was more successful and it came to dominate the first steps of the evolving Finnish elementary school. However, these two ideological streams have both been influencing, in some form, Finnish school throughout its history.

This complicated and particular history of educational philosophy is, of necessity, also reflected in the implementation of ideas about free education in Finland. This makes Finland an interesting case in thinking about both the practicalities and conceptual lines of everyday utopias in the interstices of differing state and education ideologies in Europe.

(One can also see differences between liberal and Hegelian traditions in legislation. For example, if one looks at criminal laws in liberal tradition countries, such as England and the Netherlands, the child was culpable from early on whereas in Finland the age of culpability has been higher.)

In the US, open schooling and alternative educational concepts are usually associated with the 1960s. It is thus interesting that Summerhill was already operating in the 1920s, a period usually thought of being concerned with an entirely different set of issues. However, as Gorman (2014) puts it, both eras – especially the 1960s – “had their fair share of the impersonal consequences of a modern industrialized society”. The early decades of the 20th century also witnessed a certain shift from Hegelian idealism towards positivism and Rousseauian self-regulation in the Finnish philosophy of education. For example, Waldemar Ruin (1905), the Professor of Pedagogy and Didactics at the Helsinki University, wrote that humanism could not see the child. For him, only Rousseau had brought the promotion of the child’s happiness into focus.

Rousseau stressed the importance of learning through concrete things in a natural environment, with the help of the senses. The same idea was adopted in Summerhill where children were encouraged to build tree houses and play in the forest without adult control, a practice that quite clearly originates in Rousseau’s ideas. In Émile, he promoted Robinson Crusoe as the ideal (and the only) book that a child should read before its 15th birthday – provided that those parts where the “corrupting” Friday enters the scene were cut.

As a result, Robinson Crusoe was the first fiction book that was read in all parts of society in the global North thereby instilling two centuries of children with ideals of courage and fearless enterprise.

In line with this Rousseauian praise, the Finnish school reader contained a short story about two boys who wanted to play Robinson. The story was considerably adjusted, however, as the adventurous boys, looking to encounter nature independently, soon returned from their deserted island to the safety of the family, where mother’s pancakes and the joys of the domestic sphere were awaiting them. The success narrative of individual genius was thus not impressed quite so heavily on Finnish children as it might have been in other countries: while it was fine to try to go it alone, failure to cope was also permitted, even embraced. Immediate “results” were not expected in learning how to be independent, as society in the form of the family network was readily at hand, supporting the child in growing up “slowly”.

Experimental Education and the Modernizing State

It was only in the 1960s that A.S. Neill’s ideas were actualized in Finland, in a concrete way. Generally, the decade of the 1960s is of a particular national importance, as a deliberate shift in governmental politics from an agrarian society to a modern state was taking place, and rapid urbanization and democratization processes were changing the country in profound ways. A group of liberal and leftist intellectuals worked tirelessly throughout the decade to modernize the course of Finnish education, legislation, economics and the social policy system. The notion of comprehensive schooling had already been seriously discussed after the war, as it became more common for children to go to middle and upper secondary general school, and as from the 1960s also tertiary level education expanded rapidly as families got wealthier and wanted a better education for their children.

The after-war challenge in Finland was to fit all the children in the large age groups into primary schools. Finally, as a result of a somewhat heated political debate, experimentation with the comprehensive school began in the late 1960s, aiming at guaranteeing primary school education to all children. A law on the basis of the education system was enacted in 1968, introducing a 9-year universally free municipal comprehensive school. It was implemented from 1972, starting from the north of the country and working south, completed finally in Helsinki in 1977. The current result is a statutory school age, covering the age groups 7 to 16, and a person cannot be freed from it.

Those actively creating the new democratic schools in Finland also often welcomed Summerhillian ideas. The main ideologist of the comprehensive school, Erkki Aho (Head of the School Ministry from 1973 to 1991), for example, was present at the inaugural meeting of the Free Experimental School Association in 1969 in Helsinki. The meeting consisted of a wide array of psychiatrists, MPs, psychologists, journalists, professors, artists, theologians and students, and it was moderated by a well-known feminist activist, Marianne Laxén. The meeting decided to invite A.S. Neill to become a support member of the advisory board of the association.

The original idea of the Free Experimental School Association was to establish a Finnish Summerhill School. But during the tumultuous period that marked the implementation of the comprehensive school system, it did not appear to be an appropriately democratic project.

However, to the most enthusiastic Finnish Summerhillians, it made sense to create a free kindergarten, which could later be transformed into a school. Hence, Lastenpaikka, a Summerhillian kindergarten, was opened in 1970. It was seen as an experimental site that could work as the basis for creating and testing ideas to feed the evolving Finnish preschool system. The school has yet to be actualised in Finland, the idea has been revived recently by activists in social media and meetings in Turku. One idea that has already been implemented has been to establish a ‘free’ online Feeniks School. It follows the pattern of home schools first made popular by hippies, and later adopted by extremist Christian sects, mainly in the US.

Renegotiations of Ideas and Principles

In the Finnish Lastenpaikka, the core idea was originally to strengthen the spontaneous creativity of the child in the face of the repressive authority of adults. Children were seen as being equal persons to adults, with their own rights. Lastenpaikka kindergarten was understood as an extended family that created a safe environment for children to grow in. Education freed from bureaucratic restrictions was seen as an important element in the growth of independent life and in taking responsibility for oneself and others. This conceptualization of rights and freedom departs from traditional liberal thinking in its stress on the happiness to be found in social life. Nonetheless, in its close proximity to liberal thought it does not fully meet the mainstream Finnish traditions in education philosophy.

For example, Z. Topelius, the most influential author in the creation of the cultural figure of the Finnish “child”, wrote in the 19th century: “What is a normal child? I do not expect you to answer me: an innocent child. The child is innocent only in that it is not responsible for its acts”.

Today, Lastenpaikka continues operating in its original location in the middle-class Helsinki suburb of Pakila, characterised by 1950s’ one-family wooden houses. The City of Helsinki has reduced its freedoms in considerable ways during the last years. It struggles for its existence against the representatives of dominant early education ideology – not unlike the original Summerhill School in Britain. However, while its working principles have been adjusted and renegotiated many times, A.S. Neill’s ideals of ‘free’ education form the deep basis of its everyday organizing, for example, that children should be largely left to play and learn without knowing adults, in a site that offers plenty of options for playing.

Experiencing the Utopian

In the mid-1970s, some of the original ideas of Lastenpaikka had already been changed but it was still resolutely utopian, alternative and experimental. Matti Eräsaari, now a 39-year-old anthropologist of Fiji, entered the kindergarten at this point as a child. In what comes below, Matti is reflecting, in my interview, on how experience of two years in alternative early education influenced on his adult personality and idea of self.

In the mid-1970s, some of the original ideas of Lastenpaikka had already been changed but it was still resolutely utopian, alternative and experimental. Matti Eräsaari, now a 39-year-old anthropologist of Fiji, entered the kindergarten at this point as a child. In what comes below, Matti is reflecting, in my interview, on how experience of two years in alternative early education influenced on his adult personality and idea of self.

Antu: Matti, how would you describe your relationship to the Utopian now; have you in your adult life consciously looked for, or built, utopian-like places to live?

Matti: I LOVE Utopian as a theoretical idea but the trouble lies at the concrete level – I am much too pessimistic to believe in it. Yet I dream all the time about some utopia that I could believe in strongly enough to be able cast myself into it. Ideas and principles are, however, easier for me than a practice. I can stand behind my principles even when I do not believe that these could be actualized in real life.

Antu: Yes, I can definitely relate to this. People enter utopian sites from many different backgrounds and traumas; hence, a really strong leader is required to keep it all together– which in turn may prove ethically problematic because alternative communities are often built on equality ideal inherent in utopian daydreaming. A.S. Neill actually faced this dilemma with kids kicked out of public schools for their unsocial behaviour but “too old” to benefit from the Summerhill education – some of them became bullies and the younger kids were affected by them. I also read an interview of a former Summerhill student who was expelled from the School for theft and other harm – thus individual freedom apparently has its limits in terms of the benefit of the wider community, even in Summerhill.

After the alternative kindergarten, Matti first enrolled in the private Finnish-Russian School in Helsinki, along with other kids from his agecohort from Lastenpaikka. Soon, however, he was separated from his peer group when his family moved to the small Finnish city of Jyväskylä and he entered a comprehensive public school, which had started there in 1973.

Antu: Do you see a difference between your experiences of the children’s culture in Lastenpaikka and in the comprehensive school?

Matti: I think that the moment when I understood that I had adopted a new “ethos” was in my new hometown Jyväskylä, maybe two years after we had moved away from Helsinki. I met a group of my old mates from Lastenpaikka and the Finnish-Russian School. There was some kid we did not want to hang out with, and I suggested that we should get rid of him. The other children told me that this was not the way to handle the situation – it would not feel nice for the kid. I then made another inappropriate suggestion: I started to share my candy with others when this “wrong” kid was not around. Again, the other children told me that it was not a right thing to do. When I defended my position by explaining that we had too little candy they corrected me: “A good person will share even if they don’t have much, a bad person won’t no matter how much they have.”

At that moment, I remembered that “this is how we always did it” in Lastenpaikka. I understood that my new mates in Jyväskylä were acting on the basis of a totally different set of rules than my old group from the free education kindergarten: that in this new “normal school” gang other kids can be shunned; that it is OK to refuse to share candy with everyone present, etc.

I had never before realized the difference between these two different spheres of rules that had been actualized in my child life. But when I realised it, I felt ashamed at once, because the morals of the old Lastenpaikka gang felt right – and my alienation from it felt wrong.

Antu: Davina Cooper argues, in her book on everyday utopias, that belonging is a constitutive part of the Summerhill School: even though A.S. Neill’s daughter owns the premises, the School also belongs to the children as “something precious and potentially fragile with which they are entrusted”. What do you think about this?

Matti: So far as I understand, Lastenpaikka encouraged exactly this kind of being and acting in the community. The background for this was the explicit ideal of equality, even though I do not remember how it was taught to us kids.

Antu: Summerhill children’s identities are more internally than externally generated, claims Gorman. In his approach, in viewing the curriculum as a development, or as a becoming, or as a pathway, or as, perhaps, a milieu, these open and ethical views can find sustenance and support in the actual lived experience of former students, and thus function as the living proof in its former students’ adult lives. What are your views on this; in which ways your self-image has been influenced by alternative education?

Matti: I would say that Lastenpaikka produced self-confident, extroverted children, but what kind of self-image can be attached to this? It is difficult to speculate on what was created in the kindergarten and what comes from somewhere else. I am quite confident, however, that the fact that I am confident about my own understanding and skills in problem solving in acute situations may be seen as a heritage from alternative education.

Antu: Did you experience some kind of a cultural shock when you entered the comprehensive school after your early years in radical kindergarten?

Matti: The shift from the combined alternative world of Lastenpaikka and the Finnish-Russian School that I had experienced in Helsinki happened like a shock when my family moved to Jyväskylä. I mean: the shift from the free education kindergarten to a very disciplined Finnish-Russian Elementary School was nothing special, since it took place together with other kids from my Lastenpaikka group. The older kindergarten children had also told us what was waiting for us. But it was the shift to a normal non-metropolitan Finnish elementary school in Jyväskylä (mid-1st grade) that came as a shock. I had no skills at all! I was sitting and raising my hand to teacher’s questions in a too disciplined manner, because this was how I was raised to behave in the Finnish-Russian School; I could not sing the normative Christian songs which all the other kids memorised without notes; I tried to teach to my new friends that one cannot talk about “Russians” (“ryssä”) in a dismissive way, and that bad guys do not fight with MIGs… Finally, I befriended a Swedish-speaking boy who was as equally “out” in a Finnish-speaking school as I was in the “normal” sphere of the comprehensive school in Jyväskylä.

Antu: Do you think that your alternative education experience has influenced your own views on education?

Matti: I have noticed that I am reflecting on my psychological inheritance from Lastenpaikka all the time with my own child: she is really strong-willed and stubborn, and I am quite proud of this! I even take some credit for it, because I have let her do her own decisions from the start of her life (and so has my spouse): “Do you want to do X or Y? Shall we take bikes or train?” Etc. I know that most parenting manuals tell you that the child should not be allowed to decide on too many things on her own, but it does not seem to have affected my daughter in any negative way. But then again, we, as her parents, have been affected: nothing ever happens quickly as the child has the power to influence things, and she never accepts ungrounded imperatives but offers strong counter-arguments if one tries to tell her what to do.

But I think it is great wisdom to be capable of questioning things that are offered to you as self-evident, and to assess arguments that have been presented to you as something natural or righteous.

Antu: It is really interesting to note that a sort of “slow education” or pedagogy could be seen as one of A.S. Neill’s heritages. What you said, Matti, about a confidence on your own understanding of things, capability to make judgments, and skills in problem-solving, must be a very positive thing in your personal life. It sounds to me that here Rousseau and Hegel, Neill and Snellman happily shake hands with each other.

Thank you Matti for sharing your experiences and views! Big thanks also go to Pirkko H. Hynninen and Eira Juntti for sharing their expert views on education to support this essay, Marie-Louise Karttunen, and the Birmingham Law School and the Head of The School Rosie Harding for providing me a nice environment for writing it in November –December 2014.

To conclude, I would like to refer to Sara Ahmed (2014), who writes that when a structural problem becomes diagnosed in terms of will (in this case, weak motivation as an explanation for failure in education) then individuals become the problem. The idea of slow education for the masses is incredibly untrendy at the moment, but it is a utopia worth supporting and fighting for; one promising to produce not robots but “objects that refuse to be containers” for happiness.

It is better to fight for the right to create a meaning for life than to be filled by it.

Further reading

Ahmed, Sara: Willful Subjects. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014.

Cooper, Davina: Everyday Utopias: The Conceptual Life of Promising Spaces. New York: Duke University Press, 2013.

Gorman, G.: A.S. Neill’s Summerhill: A Different View of Curriculum and What It Has to Do With Children. (read 1.12. 2014).

Korpikallio, Jaakko: Yksilön ja kansalaisen kasvatus Englannissa I: Kasvatuspäämäärän kehitys renessanssista nykyaikaan [The Education of Individual and the Citizen in England I: Development of the Aim of Education From Reneissance to Present]. Helsinki: Kauppalehti, 1937.

Pakilan Lastenpaikka [Children’s Place in Pakila]. (read 26.11. 2014)

Neill, A.S.: Summerhill School: A New View of Childhood. New York: St.Martin’s Press, 1960.

Paulsen, Friedrich: Saksan kasvatusolojen historiallinen kehitys. [Das Deutsche Bildungswesen in Seiner Geschichtlichen Entwicklung. Teubner, Leipzig 1906]. 1st edition in Finnish published in 1918.

Reich, Wilhelm: The Invasion of Compulsory Sex-Morality. [Original Publication: Sexpol Verlag 1931 and 1935, Der Einbruch der Sexualmoral: Zur Geschichte der sexuellen Ökonomie]. 3rd edition published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux 1971.

Reich, Wilhelm: The Sexual Revolution: Toward a Self-Governing Character Structure. (Original Publication: Muenster Verlag 1930, banned from circulation by U.S. Federal Court order 1954,burned under FDA supervision 1956 and 1960).Re- published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux 1962.

Rousseau, Jean Jacques: Émile; or, Treatise on education [Émile eli kasvatuksesta 1-2. Ranskankielestä suomentanut sekä johdannolla ja selityksillä varustanut Jalmari Hahl. Filosoofinen kirjasto III. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1905]. English translation by William Harold Wayne, 1892.

Ruin, Waldemar: Onnellisuus ja kasvatus [Happiness and Education]. Helsinki: Frenckell, 1905.

Snellman, J.V.: Valtio-oppi [Philosophy of the State]. Kootut teokset II. Suom. Heikki Lehmusto. Porvoo: Werner Söderström 1928 (1842), 7-280.

Svanström, Maria: Oppimisen aika [On Slow Thinking]. Sukupuolentutkimus (2014) 27;4, 58-62.

Tuononen, Mika: Education in Finland: more education for more people. Statistics Finland 2007.

Topelius, Z.: Lehtisiä mietekirjastani [Notes from My Diary]. Porvoo: WSOY, 1965 (1898).