Áine Mangaoang

The nicest prison walls in the world?

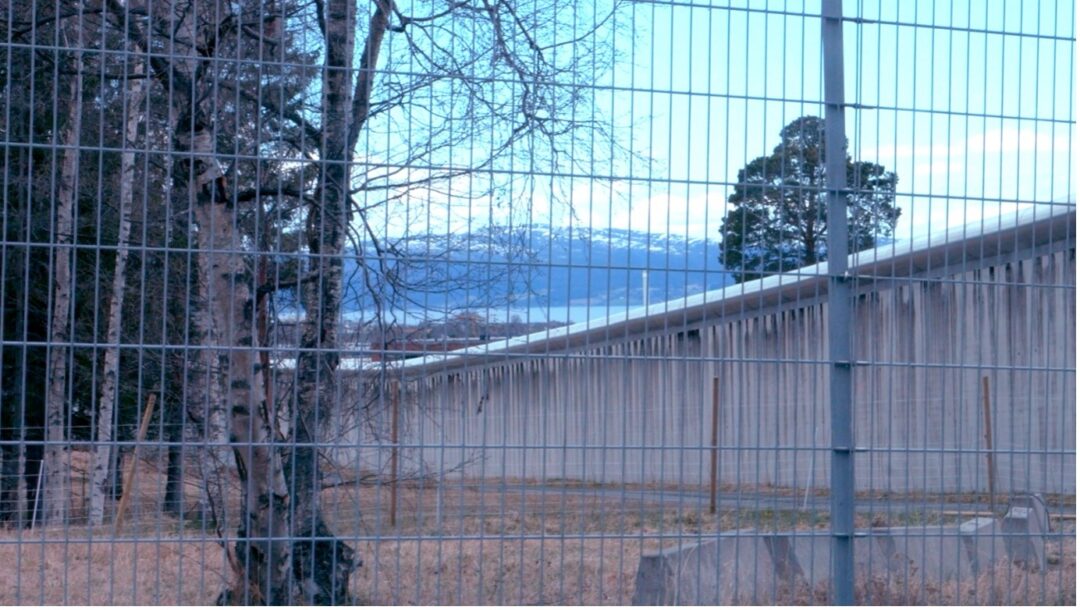

The prison begins, and ends, with the wall.

Ten-feet tall, smooth grey concrete, stretching around the perimeter of the vast prison complex to form a perfect enclosure. Nothing but one great, green metal door to get in and out of this high-security facility.

Outside of these walls, you are free. Free to do what you want, when you want. Free to be whoever you want to be, see whoever you want to see. At least that is how it seems, I’m told, from the inside looking out.

You show up at this gigantic green door one morning, 8 o’clock sharp, palms sweaty, stomach churning. You stand outside the wall and breathe in slowly, as if the air will somehow change when you walk through the threshold.

“Everything is going to be okay”, you tell yourself. “Norway has the nicest prisons in the world”, the newspapers say. “This must make these the nicest prison walls in the world”, you contemplate.

You wait a bit longer and eventually ring the bell. A voice inside the prison answers the electronic buzzing sound, asking questions through the two-way intercom. Introductions are made, explanations are given.

“We’ve been expecting you.”

From above, the security cameras confirm your identity to the voices behind the walls so that the gate slowly opens. An officer in uniform arrives to escort you in, and you hear the gate slowly close with a clang. Metal detectors ring “beep, beep, beep”. Your muscles tense up. The officer picks up a handheld metal detector and moves it slowly up and down your body, searching until he locates the item that triggered the alarm. A belt buckle is revealed to be the culprit and removed. Belongings are confiscated, to be stored in a locker and returned when you leave.

Walls, locks, and video surveillance – a holy trinity of static control.

As you walk through the hallways, you count all the cameras surveilling your every move. Nine, ten, eleven… twenty-two, twenty-three… you lose count as there are cameras all over. You are being watched everywhere you go outside of the cell. These audiovisual technologies cannot overcome the walls, but reinforce and re-channel their functions. Walls, locks, and video surveillance – a holy trinity of static control.

In the days and months that follow, you quickly learn that inside these walls is an entire world separated from the one outside. A school, a workshop, and a little library. A doctor’s office, a grocery store, and even a chapel. A village, almost, with pockets of normalcy, almost. In this enclosed village, half the people come and go every day. The others must stay inside until their debt has been repaid. For the safety of society.

In this manner, these walls separate and categorize, disconnect and designate the innocent and the guilty. The walls keep you apart from the community, while still, paradoxically, a part of society – yet one that remains invisible to those outside the prison walls.

Behind these walls, the world keeps turning; yet time seems to stand still for you. The seasons come and go, observed through small windows in the cell where you spend up to 23 hours of the day. From here, you watch the snow settle on top of the walls, piling up like mini-mountains. “There’s no summer or winter once you land inside here,” as Ewan MacColl (1959) sings.

Doing time. Keeping time. Counting days. Then weeks and months until years have cleared. Ten years down and it will be the longest you’ve stayed in any one place. Still, the walls remain the same – maintaining the boundaries of exclusion, obscuring attempts to know about the world outside. Yet people in prison are inventors. Lacking the ability to physically transform this world behind bars, you concoct ways to transcend them: through letters, carefully-timed phone calls, and specially composed songs. Necessity breeds creativity. And as Angela Davis (1974) remarked, walls turned sideways are bridges. Bridges to a future unknown, just beyond the horizon.

Doing time, keeping time, counting down. Prison begins, and ends, with these ten-foot-tall walls. A foot for every year (Heaney 1998).

References:

Davis, Angela Y. 1974. Angela Davis: An Autobiography. Chicago: Random House.

Heaney, Seamus. 1998.“Mid-Term Break” from Opened Ground: Selected poems 1966-1996. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

MacColl, Ewan with Peggy Seeger. 1959.“The Lag’s Song” from Chorus from the Gallows. Topic Records 12T16.

Nina Grønlykke Mollerup

Sensory Imagination

Walls bind our senses.

As you read this, I invite you to move yourself to a small, confined space or perhaps sit on the floor, against the wall.

Now, let’s try again.

Walls bind our senses.

They blind us to the horizon that might be visible behind it. They restrict sounds and smells which might otherwise reach us unhindered. And by limiting our mobility, they confine our tactility. We cannot touch what is beyond the wall. While this quality of walls can be a liberating and protective feature, turning a place into a home, it can also be a disruptive and obtrusive feature, making walls a powerful weapon to control others. Because walls limit and regulate our most fundamental relation to the world – the sensory.

[…] the imagination is not free. It is bound by what we have experienced […]

Yet this exact restrictiveness of walls might also be liberating. As Samuli Schielke (2019) has shown us, the imagination is not free. It is bound by what we have experienced, what we have sensed, creating material for us to imagine with. So, while walls limit our sensory engagements with the world, this might be exactly what turns them into a powerful tool of the imagination.

When you cannot see what is behind the wall, it is yours to imagine.

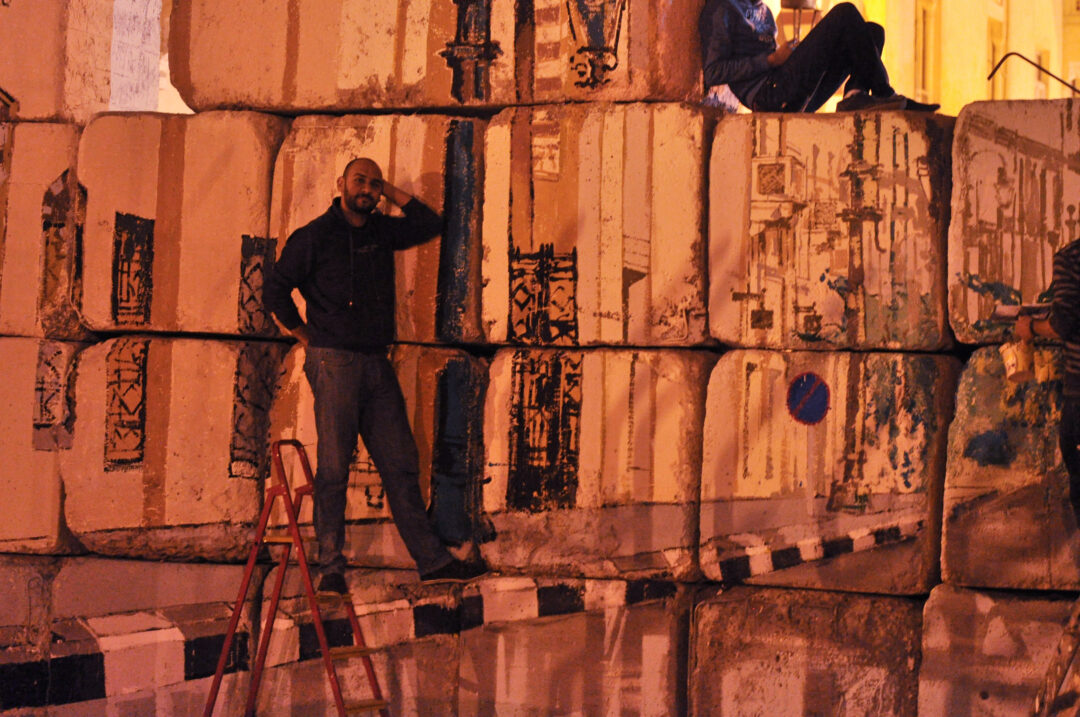

Cairo. Late 2011. The military has built large walls that completely block off streets around downtown to control the movement of protesters and, especially, to keep protestors at a distance from the Ministry of the Interior. These walls fundamentally alter movements in the city. A quick five-minute walk has turned into a 45-minute trek. But Cairo in late 2011 is not any place and time. As Alaa Abdel Fattah (2022) has pointed out, revolution is a time of imagining things differently. And in this sense, Cairo 2011 is most certainly a time of revolution. Despite the repressive function of these walls, they inspire imagination. Street artists turn walls into canvases through the pensive strokes of their brushes, and a new city emerges. A city made out of imagination, espoused by these walls.

One wall is painted as a continuation of the street which is no longer visible, complete with buildings, trees, and military police in full riot gear arrested in their movement towards the peacefully observing viewer, unable to do harm, controlled by no one but the artists now. Another wall is adorned by a rainbow and children playing, ushering in a time when streets in downtown Cairo were taken over by children playing in the streets for a brief moment in history.

Other places. The time that followed. While walls have inspired imagination and play in new ways, walls are also increasingly used to restrict movement in old ways. Prison walls. Walls that are not being used to distinguish the innocent from the guilty. Protesters are locked up. Political dissenters are locked up. Journalists are locked up. Unlucky passersby are locked up. Thoughts are not arrested, but their movement is. Sometimes, books and newspapers, paper and pencils are allowed to move in and out of cells. At other times, they are not. Prisoners find ways of speaking together, co-writing even – though writing is a different type of endeavor here, dependent, amongst other things, on the ability of sound to not be entirely bound by walls. Occasionally, scribblings on whatever paper is available are smuggled through. At other times, family and friends note down words when visits are allowed. In different ways, thoughts escape. Thoughts driven by an imagination that is unbound by walls.

Walls might bind our senses. But they work differently on the imagination.

References:

Abdel-Fattah, Alaa. 2022. You Have Not Yet Been Defeated. London: Fitzcarraldo.

Schielke, Samuli. 2019. Migrant Dreams. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Niamh Ní Bhroin

Troubling the ecological affordances of walls

Old stone walls indicate the border between our farm and the forest. With bulging boulders below and stacked with smaller stones above, these walls mediate the inside and outside of our property. They are an ancient public statement signifying protection, security, and boundaries. Like most walls, they were built to last – to keep some things in and hold others out. Our walls have survived for hundreds of years. I look at them and wonder how much effort it took to build them. There were no machines, no tractors, and no engines then. Only humans and horses with wooden levers constructed these walls on site and ad hoc from materials available in the forest.

It must have seemed very important to make a mark […] between what is tame and what is wild.

It must have required enormous strength to lift the stones into place and ensure that the wall was constructed so that it would last. What expertise, what knowledge decided how this should be done? How much of this knowledge has been lost, while the physical manifestations of intentions and meaning-making remain? I wonder how much time it must have taken – and what other tasks were set on hold – while these walls were built. It must have seemed very important to make a mark – to draw a border between what is inside and outside – between what is tame and what is wild.

When these stone walls are heated by the sun, the stones stay warmer than the air around them. This makes them a great nesting place for geckos, lizards, snakes, and other cold-blooded animals. Whether we like it or not, these creatures nest in the crevices of our construction, making our physical borders – our signifiers of boundaries – their homes. They sense and interpret the affordances of the walls in ways that are different than ours; they are indifferent to human history. The seeds of wildflowers and berry bushes carried by the wind also find favorable places to root and bloom, bringing seasonal celebrations of colors and smells to the solemnity of the stones.

Over time, even these strong walls reveal their vulnerabilities – rupturing here and there, succumbing under the pressures of the atmosphere, the passage of time, and the changing priorities and conditions of life. Now it seems that it is our responsibility to fix them: to re-erect these borders, reinforce these statements of control, and at the very least, ensure that the damage we witness does not gather momentum dragging more of these old walls with it.

These vulnerabilities signify the ultimate futility of boundaries, of the human aim to possess and control. They also raise questions about our common understanding of walls as symbols of strength and (human) dominance over nature. Over time, things change, both socially and politically, as well as materially. Even walls cannot restrict life and freedom forever. In fact, they serve both as interventions in and connections to our broader ecological surroundings. Years of wear and tear, of weight, and of pressure take their toll.

Nature takes its course.