Once again, in November 2019, I found myself in an SJVN waiting room. But it was a new waiting room. Many things had changed in the two years since my last visit to the Arun valley in Northeast Nepal. Most importantly, after ten years of planning, measuring and assessing, construction work for the Arun-3 hydropower project had started. Also, the developer SJVN – Sutlej Jal Vidyut Nigam, or Sutlej Hydro Power Limited – had taken full possession of the large plot of land close to the airport in Tumlingtar that had been bought by the government of Nepal during the first attempt to build this dam in the 1990s. Over the past decade, I had visited SJVN offices in Khadbari, Kathmandu, and New Delhi, but this here was something new: a real compound, with high brick walls and a main gate with security personnel. In front of the main gate we ran into three young Indian engineers. Udisha introduced herself as a PhD student working on Indian dam building in Nepal and Bhutan and said that we had come from Kathmandu to talk to one of the executives. One of the engineers, let’s call him Manish, called his superior, announced our arrival and asked us inside the compound.

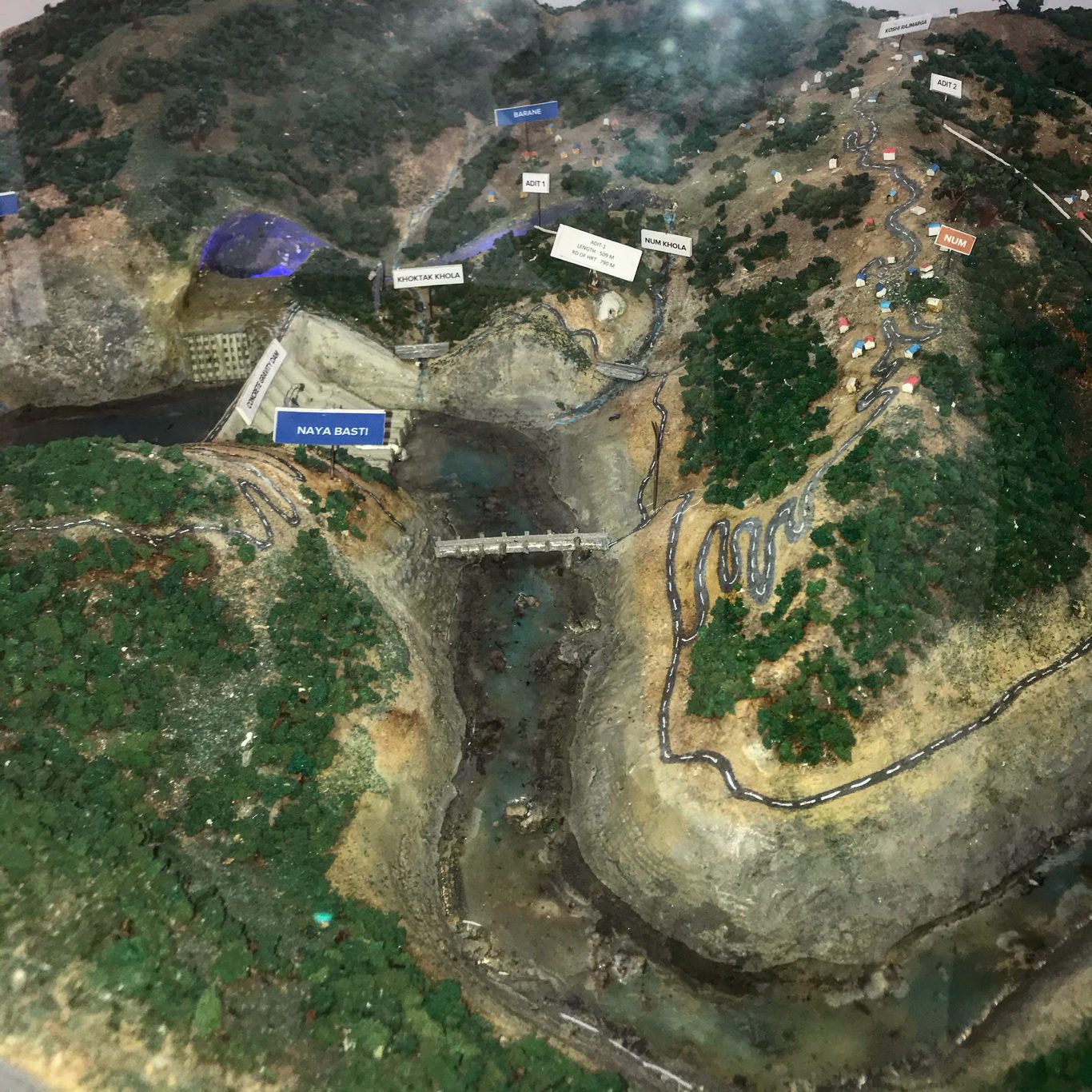

It took Manish half an hour to return. In the meantime, I took pictures of the model of the hydropower plant that was located in the entrance of the building and wondered whether the high walls were connected to several instances when homemade bombs had been planted around the project site over the past years. When the young engineer came back, his face had darkened. He was very sorry, but his superior would not be able to see us because we did not have a written permission from the Investment Board Nepal (IBN). When we replied that indeed we had and showed him text messages from a senior staff member, he became even more obscure. Even if we had a written confirmation by the IBN, he mused, we might also need a document by the Indian embassy confirming our good intentions. “I’m very sorry, but some bad people have come recently. It is very difficult for us.” He was clearly uncomfortable throwing us out like this.

I, on the other hand, was surprised. For a decade, I had interacted with SJVN staff on at least a dozen occasions, most times without prior notice. Once, as a first year PhD student, I just walked into their New Delhi office and asked to talk to the head of the international department after three days of unsuccessful attempts to get an appointment by phone. I was handed some tea and asked to wait. My preferred interlocutor was not available because he was on assignment in Bhutan, but after ten minutes, one of his assistants asked me into his office and took an hour to discuss the company’s international strategy.

Obviously, something fundamental had changed.

Udisha and I stuck around in this awkward moment for a minute or two, restated our purely academic interest in the dam, but it was clear that Manish had been told to get rid of us and our time inside the compound was over. We asked him to tell his boss he should check back about us with the Investment Board and left our business cards with him. I told him to give us a call if things would change as we would be heading up the valley in any case. “Oh really,” he asked audibly irritated as he walked us back to the main gate, his voice insecure, “you are going up to the dam site?”

The Arun-3 is a peculiar dam: for a whole generation it has refused to materialize. From what we know right now, the project will probably start producing electricity sometime in the mid-2020s. This will be forty years after the project was first proposed in 1984. At the time of its inception, it was a big dam for Nepal, but from the perspective of the World Bank – the lead investor – it was a decidedly unremarkable project. A so-called peaking-run-of-the-river hydropower plant with a 60m dam and 402MW of installed capacity, a 50-hectare storage lake, 300 meters of hydraulic head and an 11km tunnel to divert the water to the turbines. On top of that, initial assessment had indicated little complication concerning social and environmental problems. No villages would be submerged, just a few dozen families would have to be resettled for the access road. But until 1995, when the Bank cancelled its credit negotiations with the government, this unremarkable dam somewhere in a remote valley in the Himalayas had made global news.

Arun-3 had become the symbol of everything that was wrong with the World Bank’s form of international development: environmental degradation, social upheaval, rampant corruption, excessive indebtedness of recipient countries in the global South. In its cancellation, Arun-3 suddenly also became a possible symbol for a new development paradigm.

While the anti-Bank activists in the global North celebrated, Nepal’s politicians and their counterparts in the Bank were shell-shocked. The activists in Kathmandu who had started the campaign were unsure what to make of their unexpected victory and whether it would help or hinder their demand for “better” dams. To many people in the Arun valley, once they learned about that decision made in Washington, DC, it was a big disappointment.

They understood that without the dam, all the other promises were obsolete: no dam meant no road, no employment, no development.

Many of those who could afford it had already bet some money on the promise of the dam and had bought land along the two possible routes of the road, hoping to profit from the increase in land value. Almost twenty-three years later, in May 2018, at a luxury hotel in Kathmandu, two men pressed two buttons. Prime ministers Krishna Prasad Oli of Nepal and Narendra Modi of India had remotely laid the foundation stone of the Arun-3 hydropower project. The press pictures showed the model of the dam Udisha and I inspected at the SJVN compound in Tumlingtar.

Two days after our failed meeting in Tumlingtar, Udisha and I reached the construction site near Phyaksinda. Unsurprisingly, the place was hardly recognizable. It had never been much more than a river crossing, just a few houses and some small fields on the left bank of the river, a place for a quick lunch of rice and lentils before a steep climb up either side of the valley. Now all of that was gone. The construction site had taken over the whole valley floor while high above on the other side of the valley, excavators were working on the rock face, dropping shovelful after shovelful maybe 300 metres down into the river. During the last monsoon, we learned from a group of engineers, the Arun River had taken away the lower access road, so they were rebuilding it that way. Udisha struck up a conversation with the engineers who once again were interested in us but unsure who we were and what our purpose was. Normally there was no work on Saturdays, they told us, but they had made an exception that day to remove excavated material from the main tunnel system. Every few minutes a fully loaded lorry left the construction site on the road uphill towards Num. Most of them had North Indian number plates from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, some were from Bhutan.

Six hours later, on my walk back up to Num, after many conversations at the dam site and the villages around it, I ran into the first local who had actually scored a job in the project. He was working as accountant for the Gujarati company in charge of the electrical engineering. Clearly, he was happy about the dam and the development it would bring to the region. His optimism was very much in line with the stories I had heard over a decade of fieldwork. But now, it seemed, he was in the minority. All the old acquaintances I ran into had a much bleaker outlook.

Now that construction had started, most of the promises had vanished into thin air.

The landowners whose land was crucial to the project had received generous compensation packages, but otherwise nothing was settled. Nobody knew when the so-called “directly affected households” would receive the promised electrification and free electricity. The much anticipated “local shares” – the option to buy stocks of the hydropower company at a subsidized rate for local people – had been delayed to the end of the construction phase. Also the promise of employment for local people and “skills development” was clearly not executed. Even the unskilled labourers were mostly from other parts of Nepal. The most disappointing part of it was, a friend told me, that suddenly the Indian engineers were no longer talking to local civil society leaders. “With the old staff, their office door was always open. But they have all left for India. The new bosses don’t talk.” To him, our expulsion from the SJVN compound thus came as no surprise. I wondered: Is this what going native for an anthropologist of infrastructure feels like?

To peruse all issues of Roadsides, visit the journal’s website: https://roadsides.net