This post is part of our Encountering Precarities series. The thematic thread engages with the multiple and asymmetrical forms of precarisation and vulnerabilisation involving both ethnographers and their interlocutors in and beyond the field.

Uneasiness

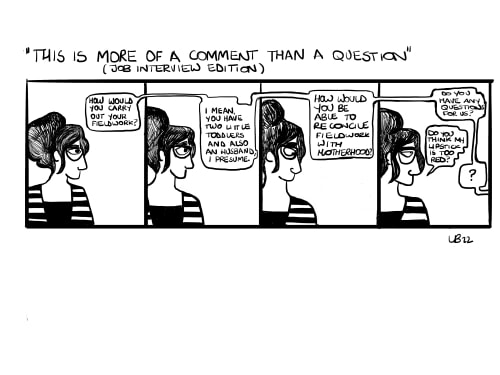

‘And how are you going to manage your family and the large time investment required by this job position?’ she asks without smiling or the slightest hesitation. I do hesitate, and smile, embarrassed. I am not sure what I should say, considering this is a job interview, and we are discussing my professional contribution to the broader research project in which I would have been involved – if only I had not had too much baggage to carry with me. My ability to respond brilliantly to any enquiry posed so far suddenly disappears. All I can think is that my lipstick definitely is too red: I should have gone for a paler shade; I really have been too bold. What was I thinking?

My mind goes blank and I am glad we are in the middle of a pandemic and this is a virtual interview. No one can hear my heart beating too quickly, or see my hand moving nervously on the side of my computer, as if searching for something to hold on to.

I could have just said something along the lines of being a professional researcher, perfectly capable of managing caring responsibilities and a high-profile job, proof being that I had been doing just that for years, and, if I may, pretty well, too. I could even have – since I already wore that bold red lipstick – brought up one of the many examples of how being a mother had, on different occasions, added value and had been a bridge for my access to fieldwork, as also highlighted in recent literature on the topic (e.g. Braukmann, Haug, Metzmacher, Stolz 2020). I could have explained at length how my last research in Chile, a two-years fieldwork experience with my then new-born son, allowed me to encounter aspects of everyday life more intensely, as when I realised the stark contrasts between private and public sectors of healthcare and education. Colleagues at a local university told me that enrolling us into the public system would be ‘absolutely reckless’ and would put my baby’s life at risk. The deep anxiety I felt in the face of what constituted both a political and an affective decision made me feel in my guts why Chile is labelled one of the most unequal countries in the region.

Or I could have just coolly pointed out that the question was rather inappropriate. But none of this came to my mind. Instead, I rambled about the arrangements myself and my partner had in place, briefly mentioning that my family could come with me on fieldwork for a short period – only to immediately add ‘at my own expense, of course’. I think that she did then, in light of my confusion, smile. To my relief, the interview concluded shortly after. I did not get the job, but this is not my point here. I want to reflect, instead, on my own embarrassment and incapability of putting together a proper answer to an improper question, unable to stand up to the challenge that I was not apt to undertake academic research, and more specifically anthropological fieldwork, because I am a mother. And just to be perfectly clear: the job in question was at one of the leading universities in Northern Europe, in one of those countries that are considered progressive and ‘family friendly’. Why was I unable to say anything of relevance, listing instead family arrangements and private issues I did not have any need to explain? And why did I feel inappropriate, why those feelings of guilt and shame?

I remember a similar feeling, but in a very different situation, when I was about to start my Marie Curie fellowship. I had had my first son three months before the planned starting date of my research, and one of the administrative people at the research office at my university was quite surprised that I was going to start such a big project, and on the other side of the world, with a little baby. She very kindly and warmly pointed out that I could have requested, and easily obtained, a later start due to family reasons. No problem really, especially because there were no additional costs involved in this decision, either for the funder or for the university. Feeling like a terrible mother, I politely declined, for the simple reason that I lacked the economic conditions to cope with further months without a salary. I had already gone without a salary during my whole pregnancy and immediately after giving birth – for there is no maternity leave for precarious project-related employment and even less for ‘informal’ roles (unpaid labour) at universities.

Again, my reply contained a guilty silence.

During the first months of fieldwork, similar emotions were diligently recorded in my field notes, as I struggled with being a new and inexperienced mother, and the starting of my research project – which thankfully was in a country I already knew well, but still a few thousand miles away from family and support networks. I remember I also felt uncomfortable with my own drama, finding absolutely no relief in the obsessive reading of advices about paediatricians, ointments, and natural remedies in the WhatsApp mums’ support group from my home country. That was, needless to say, close to useless in the completely new reality I was trying to navigate with my newborn baby and supportive partner. Feeling deeply sorry for Malinowski, but more so for myself, I couldn’t help thinking how embarrassing it would have been if someone had read my field notes on the relentless and desperate search for the right nappies after a bad skin rash on my baby’s bum.

Recalibrations

The writer Hanya Yanagihara, in her book ‘A Little Life’, writes beautifully of what she calls ‘recalibration’: adjusting to another human being that is not there to fulfil our dreams and expectations, or to reassure and confirm the images we have of ourselves, others, and the world. Of how things should be. Her words resonate with my own experience of motherhood, especially in a context in which the ability to ‘recalibrate’ was shaped by the peculiar kind of ‘heroism’ and ‘sacrifice’ required by both classic fieldwork and neoliberal academia.

The first time I left my baby during the evening he was ten months old. I had to go to a meeting with a Mapuche organisation in Santiago I had been trying to contact for weeks, to discuss their participation in the collaborative research on urban indigenous migration I was leading. Their only availability was at seven in the evening. I hoped to be back home by nine, in time to breastfeed my son and put him to bed, as I always did. But I miscalculated the length of the meeting. With time passing, I started to become very anxious. I wasn’t able to focus on the conversation at all, and felt increasingly frustrated and guilty. When I finally arrived home it was late, almost ten, and my partner had already put our son to bed. He was proud to have managed this all alone, giving him a bottle and lulling him to sleep. But when he told me, I got very upset. I yelled at him, and then burst into tears. It was the first time my son had gone to bed without me. Which did not seem a big issue for my baby, but it was for me. Especially because, I later realised, I had not planned it: it just happened. This was, for me, the hardest part of motherhood: how many things you cannot control—they ‘just happen’, and there is nothing you can do about it. With time, I learnt: to let him climb and run at the playground, to try new food even if it wasn’t ‘properly’ prepared or cut, and later to ask never-ending questions of my collaborators and colleagues in the field. It is a sort of ‘letting go’, not only in terms of the freedom of doing stuff, but also, at a deeper level, in terms of embracing what does not respond to our expectations as parents. This is what Yanagihara refers to when she writes about ‘recalibration’, and what I learnt with the tiny person that was in front of me. The recognition of otherness that leaves one in a vulnerable position of fragility; the continuous negotiations of expectations and reality; the heart-breaking openness of (child-)care.

This felt even more challenging in a context in which there is no family or support network, and in which things are, so to say, less controllable than ‘usual’, risks greater, and stakes higher. No clues about the right nursery for your kids, no reliable information about the paediatrician you found in the neighbourhood, and many other little things that make mothering particularly hard.

Academic precarity and ethnographic fieldwork, both of which are related to images, practices, and claims for sacrifice and heroism, do not fit well with the caring responsibilities involved in being – and especially newly becoming – a mother. There is, here, also a clash with the traditional imagery of ‘motherhood’ in Southern European countries that demands another sort of sacrifice and, more often than not, the choice between being a mother and pursuing a professional career. If on the one side the image of the ‘lone ethnographer’ is ill-suited to describe many fieldwork experiences, characterised by the presence of children, partners and other family members; on the other side, in the specifically culturally informed context I come from, that image if profoundly incompatible with an idea of motherhood invested with similar, but opposite, claims of heroism and sacrifice.

As a result, ‘entangled families’ (Alber 2020) in and out of the field are not easily accommodated within the requirements of neoliberal academia and its job market, characterised by high levels of precarity, mobility, and intensity. In the patchwork of my professional life, both my family and my fieldwork ended up being marked by instability, with our affective relationships with people and places shaped by a contract ending or being extended, a fellowship being awarded, this or that project being granted, and many related relocations. More so lately, I find myself looking at my kids (now two, with the second one born in the UK in 2020) and wondering what they will do of their strong northern English accent or the Chilean modismos that have become part of our family lexicon. ‘Entangled families’ in the field and in the precariousness of academic jobs have to work out their footholds in bits and pieces, on unsteady grounds.

But these are the grounds in which we find the possibility of caring solidarity. In my discontinuous ethnographic practice, shaped by the colonial legacy of the sometimes schizophrenic relationship between ‘being there’ and ‘coming back here’, and by the requirements of neoliberal academia, many of the relationships I have built over the years have become treasured friendships and important political alliances. Through the fragile and partial sharing of spaces and trajectories, shaped by continuous and reciprocal adjustments of distance and proximity, not only my experience of motherhood but also, and parallelly, my experience as an ethnographer have gone through continuous acts of ‘recalibrating’.

I do not wish to make any simplistic parallelism between motherhood, European academic precarity, and the relationships with the Mapuche artists and activists I collaborate with, who are experiencing high levels of job insecurity and a range of other uncertainties. And yet the strong alliances we built through time are also based on the sharing of our different but still commensurable vulnerabilities: the tiring search for jobs and the endless writing of projects and applications; the joys and doubts about parenthood; the critiques of academia and neoliberal forms of producing knowledge. It would be impossible to transcend the givenness of historical and power relations in which we are enmeshed — their intimacies and yet also complicities with systems of oppression have to be acknowledged over and over again. Without equating different positionalities and daily struggles, it is within this history that we need to construct relationships and solidarities that do not erase, but rather inhabit structurally antagonising positions (Jaji 2018). Our vulnerabilities can be mobilised as resources and threads intertwining the patchwork of our personal and professional lives, constantly ‘recalibrating’ our positioning and relationships against the mobile and changing realities we have to confront. This might, if we are brave enough to share our somehow interconnected vulnerabilities, open up new relational and political possibilities to confront the unstableness of differently positioned grounds.

As for the interview question with which I opened, I probably shouldn’t have bothered saying any of this. I could have just exhibited my red-lipstick smile, saying: ‘Oh, I am sure I will manage beautifully. We all do.’

References

Alber, Erdmute. 2020. Afterword: From Tightrope Walks to Entangled Families. In Being a Parent in the Field: Implications and Challenges of Accompanied Fieldwork, edited by Fabienne Braukmann, Michaela Haug, Katja Metzmacher and Rosalie Stolz, pp. 279-286. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Jaji, Tsitsi. 2016. Kutumba Naye: in Search of Anti-racist and Queer Solidarities. In Ties that Bind: Race and the politics of friendship in South Africa edited by Shannon Walsh and Jon Soske, pp. 263–287. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Yanagihara, Hanya. 2015. A Little Life. New York: Doubleday.

Featured illustration by Letizia Bonanno