Introduction: Understanding as Resonance

Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård

In this third section of the thread, Understanding as Resonance, the essays explore that which happens when words are approached as sounds – be it the sounds we may share with a crow, an old cantata or the sound of speedily throbbing heartbeats, evoking the feel of fearful and much too hasty running. They ask what thinking may be and, with it, understanding, if we take the notion of resonance literally. Resonance was the term which Unni Wikan in 1992 famously employed to conceptualise a recognition of sameness in the face of diversity. A recognition which, in order to manifest, demands something of both parties, namely, “an effort at feeling-thought; a willingness to engage with another world, life, or idea; an ability to use one’s experience” (ibid, 463). More recently, the sociologist Hartmut Rosa has used the Latin etymology of the word, re-sound, to conceptualise resonance as a relationship between subject and world; “between two vibratory bodies whereby the vibration of one body […] stimulates the other to produce its own frequency” (2016, 165; italics original). While Wikan focuses on resonance as a yielding into the context of the other, and Rosa approaches resonance as a bodily sustained capacity, neither of them addresses the question of how to acquire (or not to lose) such a capacity.

In this section, knitting, listening to music while walking, and giving form to sounds through movement are ways of vibrating, respectively the pain of tragic rape, the listening of another time and the message from a crow, in one’s own frequency. Each writer uses his or her specially tuned capacities to enable experiences of resonance to form in their own bodies, allowing them to approach other bodies with attuned sensitivities. Mark Tatlow has a background as a classically trained musician. His Ph.D. project experiments with the performance of early vocal music and looks at how this repertoire might speak into a world facing a possibly catastrophic future. Mona Nicolaysen’s background as a Reggio Emilia-inspired kindergarten teacher draws art and activism into her Ph.D. work, in which she tries to grasp other ways of knowing the world. And besides being an anthropologist, the last writer Stine Puri is trained as a dancer and teacher of eurythmy. They bring these sensibilities into their work and show, each in their way, how their own experience of resonance provides an embodied understanding of phenomena inseparable from an acute sense of responsibility towards a body different from one’s own and inherently, always, unknowable. There is no mergence here then between researcher and subject, as the reviewer Çiçek Ilengiz ponders, but rather texts that in themselves may be experienced as “new vibratory bodies”, as Illengiz so precisely puts it; vibratory textual bodies produced in the in-between of “researcher and the subject of research”.

In a reflection of and paying respect to the collective nature of thinking, we have chosen to cite central aspects of the reviewers comments in each section. We hope that this openness shall inspire conversations to continue beyond the thread – beyond this present thinking.

Cite this article as: Smith, Aja and Anne Line Dalsgård. June 2023. “Introduction: Whose Thinking?”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Theorising the Then and the Now Through an Old Cantata

Mark Tatlow

In a recent ethnography workshop I decided to explore what kind of thing the performance of an eighteenth-century cantata by George Frideric Handel might be [1]. In his book “Enacting Musical Time” Mariusz Kozak writes: “I propose that an active, bodily engagement with musical sounds offers a window into a pre-linguistic, non-representational significance, which discloses music as a temporal object by retaining the dynamical nature of time.” (2020, 10) He goes on to suggest that this “implicates both the listening body and the musical temporal objects as the co-creators of time.” (Ibid.) I decided to use these ideas as the basis for an investigation of the musical sounds of the Handel cantata, as experienced in performance by my listening body.

Touching. A finger touches and depresses a key. Flesh against wood. Wood against plastic against metal. Metal against molecules of air… There is sound.

A piece of music from an earlier time can be considered, almost by definition, to have lost much of its original context. It can no longer be played or heard as it was at the time of its composition. Like an old path, it is now surrounded by what Robert Macfarlane terms the debris and phenomena of today (2012, 33). I was interested in finding out how performing the cantata might relate to walking an old path. I therefore chose a path that my body knew well, one that I had walked regularly as an undergraduate student, supposing that if I re-walked it now, I could attend to the debris and phenomena that had accumulated during the intervening years. My experimental programme was simple:

1. Re-walk the walk from outside my college room to the University Library, while

• listening to my body,

• attending to today’s debris and phenomena, and

• documenting the experience by taking photos on my iPhone.

2. Once outside the library, write some notes.

3. Return to my room by the same route.

I located the debris and phenomena in the many closed gates and grilles: barriers erected since my undergraduate days. My attention turned to the question of accessibility; who was denied access to the university then? who is denied access now?

Reading my notes and looking at the photos, I wrote, and later revised, several hundreds to help me reflect upon, contextualise, and theorise the experiment. In my mind I placed the bodily experience of playing the cantata accompaniment on the harpsichord alongside the insights I gained while walking to the library:

Touching. A finger touches and depresses a key. Flesh against wood. Wood against plastic against metal. Metal against molecules of air… There is sound. More fingers touch more keys… There is music, which touches ears and gets into bodies, and is said to be touching. Mariusz Kozak proposes that music be considered a temporal object. But can sound materialise in this way: appearing, disappearing, and reappearing? Seemingly. If a body is touched, and the touching leaves traces in the memory, something has done the touching. Is this kind of touching encompassed by François Couperin’s phrase “L’art de toucher le clavecin?” [2]

Listening. I listen, and I hear music. Now. Today. Viola da gambist Jordi Savall plays “early music;” although he insists he plays only “contemporary music.” [3] I listen, and I hear music. Now. Today. But I am touched by music that has been touched by another time, another place, another world. The past. A past that was once present, in which people grappled, as we do, with existential questions. Robert Macfarlane says that we read old paths in the then, but walk them in the now… surrounded by the debris and phenomena of today. Is this how to play earlier music?

Walking. Playing is like walking. I am a playing, walking, listening body. I walk from my old university room to my library desk, re-walking a path I first walked years ago. Then, the path was new to me. It did not reveal its memories, nor exhibit any disturbing debris, or extraneous phenomena. Now, years later, I notice all of them. I’m surrounded by gates, grilles, and barriers constructed then, experienced now. Who was denied access then? Who is denied access now? If playing earlier music is like walking an old path, shouldn’t I change how I play, how I touch?

I used two sets of keywords to help me negotiate the shift in time and relate it to the question of access to the cantata today. Starting in 1709 I followed an associative route across the centuries, only to find that in 2022 the keywords had scarcely changed

1709 keywords — war | famine | climate change | refugee crisis | plague

in 1709 mr Handel wrote a cantata about love and separation

we find it in the archive | a monodrama for

reciting | lamenting | improvising | performing

“dear walls | since I now wander around you | in vain

if once you held my Love | hold now my Faith”

which walls | bearing the traces of past togetherness

which storytelling singer | which musicians

wandering | in vain | holding faith | searching solace

was it only mr Handel’s music they sang | and played

from their store of embodied memories

(Eleonora Fabião dreams up programs

she programs herself to act them out

historiographer and performance artist in one body)

was mr Handel’s cantata first a dream | for us to re-dream | as a program |

is it OK thus to actualise an archival remnant | unsealing a reservoir of tears

once the outpouring of an earlier wanderer | may we

can we follow Robert Macfarlane

along old ways | covered with the debris and phenomena of the present

catching reflected memories | not representing | but being | delinking

ourselves | as Walter Mignolo suggests | from colonial masters

neither seen nor heard | but still holding us in their grip

This is an archival entry I wandered with, wrestled with, in my studio; closed in by walls—lovingly listening, but cruelly separating—while a screen veiled the precarity of faith in an archival future, in which dreams may perhaps be re-membered, and solace found, despite

pandemic | refugee crisis | climate change | famine | war — keywords 2022

While walking the inescapable realities of their now, Handel and his anonymous poet point to a brighter future; the beauty of the cantata’s words and music jarring with the harsh realities of its context. We cannot know if poet or composer ever dreamt the story of this cantata, not whether such dreaming may in part have been a nostalgic longing for the peacefulness of Arcadia. When you or I re-dream the story, however, we can choose to engage not with the past, but with the future; and in performing the cantata now, we can encourage the emergence of the very future we dream of.

This workshop experiment suggests that walking through an old eighteenth-century cantata can engage an audience today, if performers develop an awareness of the barriers to its accessibility. If in consequence they adapt their way of touching the audience, they can create a pathway to a brighter future

Cite this article as: Tatlow, Mark. June 2023. “Theorising the Then and the Now Through an Old Cantata”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

Knitting Heartbeats, Crafting Theory

Mona Nicolaysen

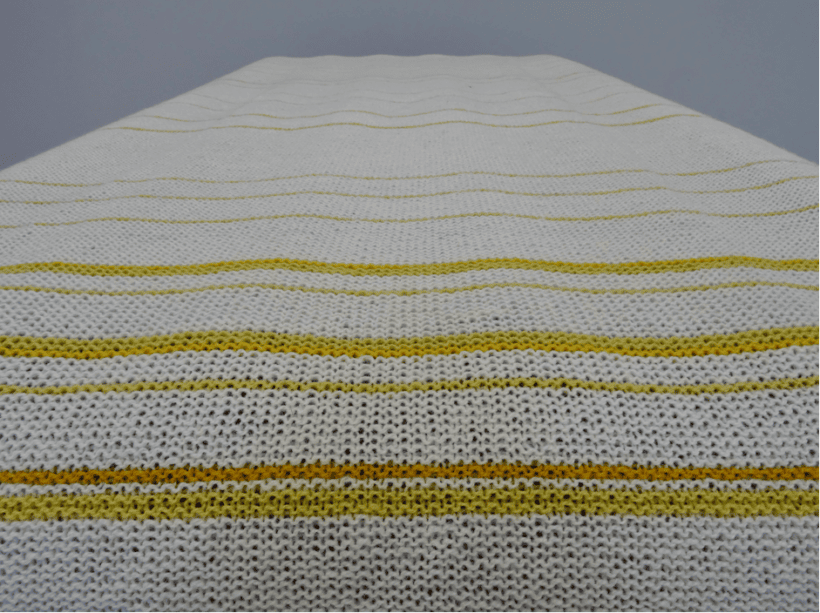

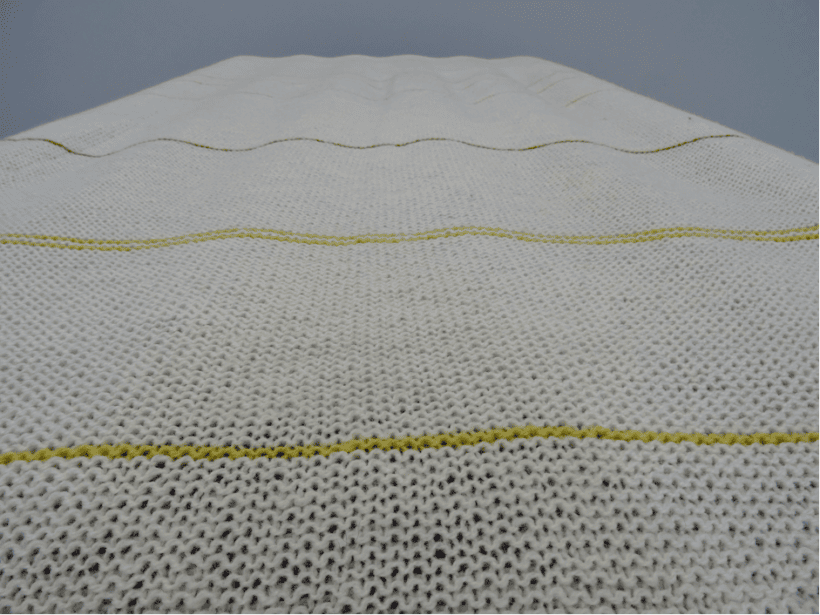

In a PhD course at the University of Gothenburg the participants were asked to bring an object from their research. I chose a stitch marker [4] shaped as a heart, and from this hundreds were written. The following three sets of hundreds and all the other words in this paper are written with ethical struggles. They arise from an artistic practice developed to grasp my field of research. My research explores spaces of aesthetic expressions and utterances for young children in Gaza. Coming to this Ph.D. research from a background as a kindergarten teacher in Norway, it was important to find a path to better understand the context in which this research is positioned. I developed the artistic practice of knitting annual statistics of people being killed by someone from the other side in Palestine and Israel, crafting throws showing each country’s loss. Before you continue reading, I invite you to get to know the knitting through the website knittingstatistics.

Hundreds of beating hearts written at the PhD course:

You know, when you’ve run so fast that your heart is thumping in your chest and others only see your chest rise and fall. When you’ve run so fast that you hear with your entire body; your pulse so loud it challenges your blood vessels and becomes a rush in your ears. And if someone puts an ear against your back, they will hear the heartbeats, but not sense the loud rhythmic pounding, the rushing and the thumping. They won’t know how this experience of running enters your bodily archives. And then, you’re not even scared. You’ve just been running.

During the kindergarten’s annual theme-week about the body, we realized that the boys used a range of words to describe their tissen while the girls simply said tissen. [5] With loud voices, words, laughter, humorous glances, and smiles exposing their teeth, the boys’ bodies extended into the room. The girls’ bodies folded back, as if into a secret unknown. They looked at the boys, at one another, their smiles inside their mouths. Afterwards we asked them, “If girls’ tissen were to have a name of its own what would that be?” “The flower”, one girl suggested. “The heart”, another one said.

In 2018 The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad “for their efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict”. In February 2019 a young Israeli woman was raped and killed in the Jerusalem forest by a man from Palestine. She was registered in the statistics I craft into my knitting. The database on which I draw, is made by a Jerusalem-based non-profit human rights organization. According to its webpage, it includes statistics on all persons – Palestinians, Israelis and foreign nationals – killed as a result of the armed conflict between Israel and Palestine since the second intifada broke out in September 2000,. Searching for the right kind of stitch marker to represent her and others who might be raped and killed took weeks. When eventually I found it, I had to imagine the number of this kind of killings for the years to come. I bought forty, and when I got the small, triangle-folded paper bag in my hand, my body spoke through tears.

The stitch markers cling together. As chains and clusters. Never rows. Never structured or systematized. They tangle, entangle, and untangle. As tiny rhizomatic networks stretching across generations and national borders, as transections of time, as transcending rights, violated by transgressive acts. Hidden but still tensely present in the bodily reservoir as a capacity to feel. To hold back, push forward, hold tight around the line of flight is taxing. She who was lost is marked. In the bodies of the families. In the softness of the forest floor. In the statistics. And the seasons covers the traces that once were.

Knitting the annual statistics into throws for more than four years has become a personal research practice of “staying with the trouble” (Haraway 2016). The ongoing knitting of numbers, ages and stories of victims has created relational networks, entangling information and affective embodied becomings in unexpected ways. The crafting connects questions of time, space and matter with justice. The language of knitting converts hard facts into soft throws. White rows show days without killings. A light-yellow row talks about the loss of a single person. If this person is a child, the stitch marker is green. If it is someone who was raped and killed, the marker is red, shaped as a heart.

Preparing for the course, I struggled with choosing which object to bring. Would it be more political, less ethical, to bring a stitch marker from the blanket of Israel? After all, the occupation of territory in Palestine violates international humanitarian law. Even the UN recognizes this as fact. Would it be disrespectful to the Palestinians’ collective frustration and sadness to select an atrocity committed by a Palestinian rather than one from the occupying side? And was this even an act of war? The hesitation made me call a Palestinian Muslim friend to discuss the choice and he responded by questioning how this rape and killing could be an act of liberation – or even Jihad. In his eyes it was clearly a sexually motivated act. Why should a Palestinian, Muslim or not, rape and kill a girl from Israel, Jew or not? Should this rape and killing then really figure in these statistics, figure in my knitting?

I decided not to bring the marker shaped as a heart to the workshop. Yet somehow this was the object I ended up bringing.

Searching for it (2019), choosing it, using it in knitting, choosing it for a PhD course (2021), talking about it with a Palestinian Muslim friend, deciding not to bring it, deciding to bring it, thinking it was a “dead” object, considering a change of object, keeping the object, pushing myself through the writing (2022-2023).

Working with Hundreds the association with four-year-olds discussing names for their genitals was surprising. It moved me from the question of rape in times of war, to gender questions in everyday life in kindergarten. The marker and Hundreds triggered relational and erratic networks to occur that tied together affective strings of memory (Massumi, 2015). Hundreds created a web of thoughts that were unavailable before the writing session. In the evening, trying to explore the matter further, I sat on the toilet in the bathroom recording the sound of knitting, suddenly hearing the sound of heartbeats.

Despite the wars, children in Gaza still play at the beach, eat ice-cream, navigate traffic in the busy streets, draw helicopters and go to kindergarten. If there is killing or dying happening, there is also ongoing life (Butler 2016). And I keep on walking, knitting, leaning, sitting, reading, talking to my friend, stretching, pulling the shawl over my shoulders. As if the bodily movements will make this essay easier to write, make the messy awareness easier to deal with, or soften the edge of a man raping and killing a young woman in a forest. As if the fear of nourishing potential pro-Israeli readers will evaporate as I navigate body, statistics, and theory through knitting and stitch markers. Despite the cruelty of rape as a weapon in war, I have caught myself thinking of not submitting this essay. When what was once soft in my hands touches the hardness of the world, a representation of an event may come to count as fact. What do we do when we count atrocities? To submit this essay is to allow this question to stay unanswered.

Cite this article as: Nicolaysen, Mona. June 2023. “Knitting Heartbeats, Crafting Theory”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

The Call of a Crow

Stine Simonsen Puri

I hear only three things. First the birds singing, then clicking keys, followed by a fly. No wait, I hear something else, I hear a crow. A crow doesn’t sing. It tries to speak our language or, tries to teach us to really experience the sound “Craa”. That’s how it gave itself its names; an English Crow, a Danish Krage. That crow’s so devoted to teaching us the CR sound, that it doesn’t want a name for itself, but wants a name together with the other crows trying to teach us to experience this CR sound. Back to the keyboard.

This short text came into being in a state of heightened sense perception. Three days of intensive work with movement, sound, drawing and meditation had left little time for the group of enthusiastic anthropologists to do their normal work of translating experience into concepts. Instead, we were asked to stay with the experience of the present and write in a stream of consciousness on what was around us with the only limitation that we had to stop at 100 words (as proposed by Berlant and Stewart 2019). What the text developing out of that moment revealed to me in words was something primordial about language. Namely that language is first of all sound. Sound shared. With other species. With all that is around us.

The text was not only born out of the exercises given in the workshop. A six-year part-time training program in eurythmy also fed into it. Through the practice of eurythmy, I learned to attune my body to sounds. Eurythmy is a form of movement developed by Rudolf Steiner, which was meant to bring language into movement. The subtle movements of the larynx that we learn to master through speech was enlarged and brought out as movements of the whole body (Steiner [1924]2019). Out of that developed a system of movements for each sound in the alphabet that enabled you to dance with language. It was envisioned that this could be a way of practicing a mode of thinking with language that takes place in the heart and the body. A mode of thinking that could bring new understandings. Understandings based on a cultivation of an embodied listening that was to grasp, not only the material observable world, but also the immaterial world of various forms of energies central to Steiner’s philosophy.

In the workshop titled “Embodying Understanding” we were asked to explore what kind of bodily activity understanding may be. The etymology of “understand” refers to an activity of standing before or in the middle of something. But what is that something which one stands in the middle of? Is it the grappling with language to make sense of experience? As an attempt to investigate words as an experience, I invited the participants to move the word ‘understand’. To try to get into the embodied layers of experience and meaning inherent in the concept. “Try to move your body as an S…use your arms, walk as an S, sense the S while moving”. You may also try it!

The Danish forSTå, German verSTehen have in common with the English word for understanding the ST-sound. The S movement according to Steiner is bringing something in movement into calmness (Steiner 2019, p. 49). Is brining something that is moving into calmness part of a process of understanding for you? The T in eurythmy raises the arms to capture the space above the head, and then brings the hands with a force to a clearly defined point on your head or body. [6] Do you recognise this movement of bringing something in the space above you down into yourself as part of a process of understanding? Or does it involve a more upward moving energy?

Towards the end of the workshop, while seated, we each expressed what understanding as a movement in space and time can be. The only guideline being “now speak”. With my eyes closed I said the following, here edited down to one hundred words:

When something is true, it exists, not just as an idea. Coming to understanding you have to go down, it can hurt a bit, pulling the muscles as it compounds. It feels like spiralling inwards. Then a release outwards, and there you are: in understanding. At that point understanding is easy, you can feel it. But also difficult. You must hold it, as you need to pass it on. When you understand something, it has to be moved. Not like a stone, more like a gathering of energy – of thoughts, feelings and life. That has settled into a tune.

The crow calls again. I hear new nuances in her sound. Have our alphabet and language managed to capture her sound? I try.

C – I respond to the sound with a force of moving swiftly, as if breaking through a point of resistance, and creating space for the reverberations of that force.

R –I start to make rolling movements with my upper body, as if my body is a wheel first lifting and then turning something over – I continue – it moves forward.

AA – As I get to a long A-sound I sense an opening in my whole being. I open my arms to the world, and that openness transforms into a listening to the world. I breathe.

Words are missing, but I know. I have heard her. Has she heard me? I might even recognise a CRAA force in myself as an ability to forcefully get something through to someone in moving from resistance to resounding release. Should I move it out, share it with someone else? How could I say what I experienced and understood through a language understood by peers? I will try:

Understanding something, let’s call it an object, does not just involve thinking but a “tuning into” the object. Capturing its vibrations in such a way that it is grasped as a moving object. Where one can connect with the object through its vibrations that is both movement and sound. Hartmut Rosa (2019) captures the desire for connection through such vibrations in the concept “resonance” but does not unfold its connection to language.

Another way of saying it, limiting my spoken words: words are sounds are movements are shared.

Cite this article as: Puri, Stine Simonsen. June 2023. “The Call of a Crow: Dancing and Writing on the Embodied Phenomenology of Understanding”. Building Bodies for Thought, edited by Aja Smith and Anne Line Dalsgård. Allegra Lab

References:

Barad, Karen. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

Berlant, Lauren and Stewart, Kathleen. 2019. The Hundreds. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Butler, Judith. (2016). “Fragments of lost lives”. In K. Klich (Ed), Gaza Works (p. 148-162). Koenig Books.

Fabião, Eleonora. 2012 “History and Precariousness: In Search of a Performative Historiography”. In Perform, repeat, record: live art in history, edited by Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield. Bristol, Chicago: Intellect.

Gaztambide-Fernández, Rubén. 2014 “Decolonial options and artistic/aestheSic entanglements: An interview with Walter Mignolo”, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3. 1:196-212.

Haraway, Donna. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Harris, Ellen T. 2001. Handel as Orpheus: Voice and Desire in the Chamber Cantatas. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Kozak, Mariusz. 2020. Enacting Musical Time: The Bodily Experience of New Music. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Macfarlane, Robert. 2012. The Old Ways. A Journey on Foot. London, Penguin. 2012.

Massumi, Brian. (2015). Politics of Affect. Polity press. Rosa, Hartmut. 2019. Resonance. A sociology of our Relationship to the World. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Steiner, Rudolf. 2019. Eurythmy as Visible Speech. Fifteen lectures held in Dornach, 24 June to 12 July 1924. With a Companion compiled edited by Alan Scott. Forest Row: Ruldolf Steiner Press.

Wikan, Unni. 1992. “Beyond the Words: The Power of Resonance”. American Ethnologist 19(3): 460-482

[1] A cantata is a musical composition normally for one voice with instrumental accompaniment. The text is often a narrative, told in a mixture of musical styles, each chosen to enhance the storytelling.

[2] François Couperin’s treatise “L’art de toucher le clavecin” was first published in 1716. The French title is best translated as “The art of playing the harpsichord”.

[3] At a Palladium Baroque conference lecture I attended in Malmö in February 2011.

[4] A stitch marker is a small object, often a circle or a pin, used for counting and remembering while knitting.

[5] Tissen is a vernacular Norwegian term for genitals, generally used when talking to children.

[6] see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xOiGetL9AUI