The African continent has been at the forefront of experiments with transitional justice. There have been amnesties, truth commissions, criminal trials and supposedly localized institutions such as the gacaca courts in Rwanda all with the objective of ensuring accountability for atrocities and contributing to peaceful and democratic new beginnings.

The new volume Transition and Justice: Negotiating the Terms of New Beginnings in Africa examines a series of new beginnings in Sierra Leone, Uganda, Rwanda, Mauritania, Kenya and South Africa. One characteristic feature of the debates about justice and transition in these situations is the contradiction between the official condemnation of violence, on the one hand, and the multifarious ways in which violence actually shapes the new beginnings, on the other.

Transitional justice mechanisms such as truth commissions and criminal trials have become part and parcel of attempts to achieve transitions to democracy and the rule of law in countries affected by systematic human rights violations committed by functionaries of the state and civil war. Truth commissions and courts are manifestations of a reformist and legalistic approach to effecting new beginnings; they have their foundation in legal documents including national legislation, international law or peace agreements between warring factions. For instance, the South African truth commission is based on the South African interim constitution of 1993 and the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act; the Special Court for Sierra Leone on an agreement between the UN and the Government of Sierra Leone authorized by the UN Security Council; the international criminal tribunal in Arusha on several Security Council Resolutions; and the International Criminal Court on an international treaty.

Liberal constitutionalism, rule of law and human rights are the ultimate objectives of fact-finding by truth commissions and criminal tribunals. For instance, the preamble of the South African Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act of 1995 establishing the truth commission invokes ‘a future founded on the recognition of human rights, democracy and peaceful co-existence for all South Africans, irrespective of colour, race, class, belief or sex’. Similarly, representatives of international criminal courts have highlighted the importance of criminal trials beyond the mere punishment of individuals who have committed crimes. In 2000, for instance, the UN Secretary General stated in his report to the UN Security Council that the Special Court for Sierra Leone ‘would contribute to the process of national reconciliation and to the restoration and maintenance of peace in that country’.

Truth commissions, trials and other initiatives clearly eschew the use of violence as a means to effect political new beginnings. In fact, they are often established with the explicit aim of avoiding violence by striking a political compromise between holding accountable the perpetrators of crimes and ensuring the cooperation of the remnants of the old regime. In the debate about transitional justice this political pragmatism has been framed in the opposition between truth, i.e. accountability through means or public truth-telling, and justice, accountability by punishing perpetrators. In any case, transitional justice is aimed at breaking with a violent past and realizing a new beginning – peaceful and democratic.

The explicit rejection of violence as a means to effect political and social change is difficult to reconcile with criminal trials as transitional justice mechanism. Trials are often seen as problematic because those who fear retribution may threaten to resort to violence thereby jeopardizing fragile political compromises. It should also not be overlooked that criminal trials themselves constitute violence due to the violent nature of punishment meted out as retribution, a point to which I will return in more detail.

The rejection of violence is in striking contrast to conceptions of new beginnings that have often been associated with violence. According to Arendt:

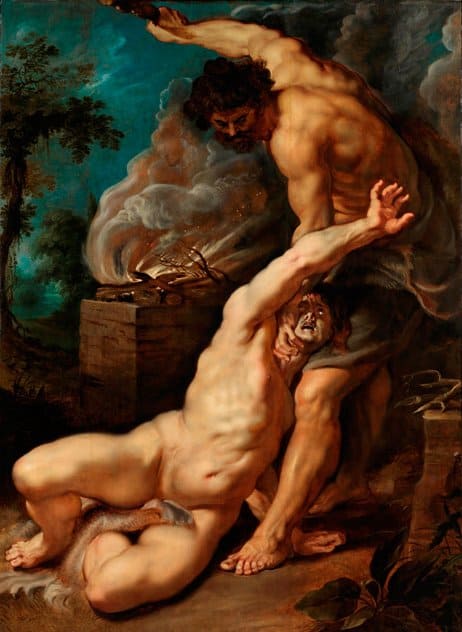

The relevance of the problem of beginning to the phenomenon of revolution is obvious. That such a beginning must be intimately connected with violence seems to be vouched for by the legendary beginnings of our history as both biblical and classical antiquity report it: Cain slew Abel, and Romulus slew Remus; violence was the beginning and, by the same token, no beginning could be made without using violence, without violating. (Arendt 1990/1963:20)

In Arendt’s analysis, the problem of beginning is key to the understanding of modern revolutions and the violence with which revolutionary change tends to be brought about. According to Arendt, the modern idea of revolution differs from pre-modern ideas of political change as it envisages the beginning of a new era, a complete break with the past to realize freedom, social equality and justice. When Arendt was writing On Revolution in the early 1960s, many African countries were achieving independence. Prominent African leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah, Sekou Touré and Julius Nyerere framed the strife for national independence in the language of revolution, socialism and Pan-Africanism and did not eschew the use of violence to achieve independence. Theorists such as Fanon explicitly condoned violence to end colonialism and emancipate the colonized populations from deeply entrenched racism and economic exploitation. In contradistinction to Arendt’s analysis of revolutionary new beginnings and the revolutionary spirit of decolonization during the 1960s, current debates about new beginnings in Africa often revolve around transitional justice and explicitly reject revolutionary violence. Transitional justice also seeks a break with the past but by addressing past injustices rather than by violent means.

However, the realities of transitional periods with truth commissions or even criminal trials might be characterized by violence. Even the new social and political order envisaged by transitional justice might rely on violence, as empirical studies show (Anders and Zenker 2014, Branch 2011). These and other studies reveal the contradiction between the rhetoric of reconciliation and justice espoused by the advocates of transitional justice mechanisms and continued violence in regions such as Northern Uganda. The discrepancy between the liberal narrative informing truth commissions, courts and localized, neo-traditional initiatives aimed at reconciliation, on the one hand, and the messy contradictory realities in the regions affected by violence and injustice, on the other hand, need to be addressed by studies of transitional justice.

The unresolved relationship between transitional justice and violence is a forceful reminder of Walter Benjamin’s Critique of Violence. This essay, published in the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik in 1921, explores the relationship between violence, law, and justice. Discussing both, natural law theory and positivism Benjamin sees violence as constitutive of legal order, as the law being latent violence. He distinguishes two forms of what he labels mythical violence. The first one is violence as a means to preserve and maintain the law, rechtserhaltende Gewalt in German, and the second one is lawmaking violence, violence establishing a new social and political order, rechtssetzende Gewalt.

In his reading of Benjamin’s essay, Derrida highlights this ambivalent relationship between law and violence by reflecting on the German word Gewalt, which denotes both legitimate authority and violence.

Paraphrasing Arendt, acts of violence such as slaying Remus and Abel constitute the mythical foundation of legal order. Not less mythical, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 represented a complete break with the past, rejecting the sovereignty of the monarch and introducing popular sovereignty.

In line with the vision of a revolutionary new beginning, there could be no legal foundation for the trial against King Louis XVI, according to Robespierre and Saint-Just, who proposed to kill the king as enemy of the newly established nation.

Arendt’s On Revolution and Benjamin’s Critique of Violence enable us to interrogate both, law-preserving and lawmaking violence in situations where transitional justice institutions are supposed to contribute to peaceful new beginnings. Violence has been a blind spot in the debate on transitional justice and the heavy emphasis on truth-telling, forgiveness, repentance and due process has eclipsed detentions without trial, political show trials, the use of armed force and other forms of violence employed to effect transitions to democracy and the rule of law. The paradox of violence employed to make or preserve law noted by Benjamin highlights the elusiveness of justice in spite of truth commissions, international tribunals and neo-traditional reconciliation ceremonies promoted by international NGOs and African governments.

References:

Anders, G. and O. Zenker, eds. 2014. Transition and Justice: Negotiating the Terms of New

Beginnings in Africa. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Arendt, H. 1990/1963. On Revolution. London: Penguin.

Benjamin, W. 1921. ‘Kritik der Gewalt’, Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik 47: 809-832.

Branch, A. 2011. Displacing Human Rights: War and Intervention in Northern Uganda.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Derrida, J. 1990. ‘Deconstruction and the Possibility of Justice’, Cardozo Law Review 11: 919-1045.

Fanon, F. 2004/1961. The Wretched of the Earth. London: Penguin.