Wherever one looks across the globe today democracy is in decline and trends towards what was once called “totalitarianism” are on the rise. In China 1,000,000 Uighurs are detained in what Chinese state media calls “counter extremism training centers”. Hong Kong’s June 2020 security law has removed basic democratic freedoms and granted extra-legal power to the mainland government. Saudi Arabian authorities are gathering large amounts of data on Saudi citizens abroad by exploiting weaknesses in cell phone tracking location systems. In Russia Putin’s regime orchestrates an assassination attempt on opposition leader Alexei Navalny using the nerve agent Novichok. Belarus’s President Lukashenko cracks down on mass protests against a rigged election on August 9 th, 2020. In Modi’s India, the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019) openly discriminates on the grounds of religion, and state authorities have arrested protesters under draconian anti-terror laws. In the Philippines President Duterte instructs police and vigilantes to kill anyone believed to be connected to the drug trade. In the United States, supported by Fox News and alt-right media platforms, President Trump wages daily assaults against the institutions of liberal democracy including measures to suppress voting in the 2020 election.

Hungary’s President Viktor Orbán openly calls for “illiberal democracy” and passes emergency legislation, under the pretext of fighting Covid-19, allowing him to bypass Parliament and govern unchallenged. In Brazil, three decades after liberal democracy replaced military dictatorship, President Jair Bolsonaro leads a far-right coalition supported by the military, evangelical groups and agri-business that deploys judicial measures against anyone deemed left-wing. In Britain, Boris Johnson’s government in 2019 suspends Parliament in an unconstitutional attempt to prevent scrutiny of its controversial Brexit plans in the weeks before the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union. In all these examples, heads of government and their supporters systematically deploy lies and misleading statements to create false realities.

What makes these trends “totalitarian” rather than “authoritarian” or “tyrannical” is the aspiration to control three key facets of a person’s daily life. The first is the outer life of public interaction, often called “public safety”. This features prominently in authoritarian regimes, and even liberal democracies, seeking to ensure a politically docile and economically productive society. It usually entails marking “others” as enemies who threaten mainstream society: “Mexican rapists” in the US, “poison” refugees in Hungary, or “drug dealers” in the Philippines. The second is government intrusion into people’s private lives. The unparalleled growth in surveillance capabilities exposes private relationships to ever-tighter state scrutiny, eradicating public-private distinctions under the guise of combatting sedition and moral transgressions. In totalitarian regimes such as Erich Honeker’s German Democratic Republic, children would report their parents’ transgressions to the authorities and family members, friends, and lovers sometimes informed on each other. In today’s China, Han officials are dispatched to live in Uighur homes in Xinjiang, a move referred to as “becoming kin.” Hosts are pressured to enthusiastically welcome them, or face repercussions.

What makes these trends “totalitarian” rather than “authoritarian” or “tyrannical” is the aspiration to control three key facets of a person’s daily life.

The third is the inner life of mind, seemingly a space where no one else can enter. This is where we reason, understand ourselves as political beings, and interpret the world we inhabit. George Orwell’s 1984 provided a powerful illustration of totalitarian intrusion into the mind: It wasn’t enough for Winston Smith to simply agree that 2+2=5 to stop O’Brien’s torture. To be a trustworthy citizen, Smith had to genuinely believe it to avoid committing a “thoughtcrime”. Intensified media environments make our interior lives an increasingly viable target of control as alt-right outlets and the algorithmic governance of social media seek to interpolate our own self-understanding. These situations facilitate spreading false histories that present the struggles of the national community in deceptively narrow ways: the revival of the Turkish age-old resistance against Byzantium and westernization, the controversial Polish memorial law rendering accusations of the country’s complicity in the Holocaust a civil offence, the political use of Hindu religious myths as historical evidence to target the country’s Muslims.

Conditions for totalitarianism

To resist or avoid these totalitarian trends we must first understand the historical conditions that enable them. The similarities between the former colonial powers and the formerly colonized are as important as their differences given that both are premised on the nation-

state form and are linked together through transnational public cultures and global institutions of finance, trade, and governance. The formation of mass society, in which people are encouraged to regard themselves as an essentialized, collective, and national whole, began with the French Revolution of 1789. Alongside positive contributions, it also rendered society vulnerable to the demagoguery of charismatic leaders who reframe the reasonable frustrations of citizens into symptoms of existential threats to nation perpetrated by political enemies. Tocqueville warned in Democracy in America (1835), that even liberal societies are not immune because the majority’s sheer force of numbers renders them prone to intellectual hubris, moral conformity, and uniformity in thought. This situation encourages hostility toward minorities.

Advances in early twentieth century communication technologies, particularly radio, enabled the “Cults of Personality” in the totalitarian systems of Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin and Mao. Personality cults made it easy for people to identify with leaders who cast themselves as independent of the lethargic, bureaucratic state, hamstrung by its need for compromise and cooperation among different social groups and political parties. The twenty-first century also has its personality cults, from President Trump’s “Make America Great Again” Movement and Putin’s displays of Russian machismo to the leader-for-life aspirations of China’s President Xi Jinping and Turkey’s Recep Erdoğan. Relying on social media, these cults similarly deploy essentialist notions of racial, cultural, or national purity supposedly under assault from foreign and domestic threats. While these notions are European inventions, they also condition politics in the former colonies because Europeans institutionalized ethnic categories through their imperial administrations. Post-colonial ethnic leaders could then rely on similar tropes of existential threat in their struggle to control state bureaucracies following the withdrawal of Empire. The tendency to conceive of people as essentialized groups manipulable through demagoguery recalls Herman Göring’s unsettling

insight:

Naturally, the common people don’t want war, but after all, it is the leaders of a country who determine the policy, and it is always a simple matter to drag people along whether it is a democracy, or a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. […] All you have to do is to tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same in every country.

Tocqueville warned in Democracy in America (1835), that even liberal societies are not immune because the majority’s sheer force of numbers renders them prone to intellectual hubris, moral conformity, and uniformity in thought. This situation encourages hostility toward minorities.

Alongside issues of politics and identity, widening inequalities and massive wealth creation since the 1980s have fuelled a growing sense of disempowerment that feeds today’s totalitarianism. In the traditional industrial countries, former leftists feel betrayed by their parties’ accommodation of neoliberalism and embrace alt-right parties believing they will protect their nation. The rise of the precariat has left millions anxious and suspicious of globalization, particularly of finance capitalism and immigration. In post-colonial countries, the shift from 1960s high-modernist development priorities to 1980s Structural Adjustment Programs has exacerbated socio-economic inequality, allowing a small class of capitalists to throw their weight behind right-wing leaders who capitalize on anxieties about a growing un(der)employment crisis and fuel a cultural essentialism that scapegoats “Others” and “outsiders”.

Struggles and resistance

Resistance is everywhere, sometimes manifesting in efforts to restore or expand traditional freedoms of representative democracy (voting rights, impartial judiciaries, racial equality, gender equality etc.) and at other times, calling for a reimagining and restructuring of a social order, which enables exclusion and denials of citizenship. The Black Lives Matter movement has brought these issues to the forefront in the United States, constructing a broad coalition across axes of difference. In India, Muslim women at Shaheen Bagh united thousands across religious, class and caste lines against the CAA and other exclusionary policies of the Modi government. Both these movements model how people can spontaneously organize spaces of direct democratic participation.

The diversity of responses to today’s totalitarianism is an asset. Despite differences among its critics, all agree that these trends must be called out and challenged. Moreover, we must not assume the totality of totalitarianism. While Orwell’s insights will take us far into

understanding today’s disturbing trends, we must recall what Solzhenitsyn, no stranger to totalitarian terrors, allegedly concluded about him: “The man is clever, but he does not understand that there is life even under Big Brother’s heel.”

Today’s Totalitarianism seeks accessible, op-ed style essays that address the broad parameters in our program statement

(https://allegralaboratory.net/todays-totalitarianism/) . Essays should not exceed 1500 words and will be single-blind reviewed. Please

contact Greg Feldman (greg@allegralaboratory.net) for queries and submissions.

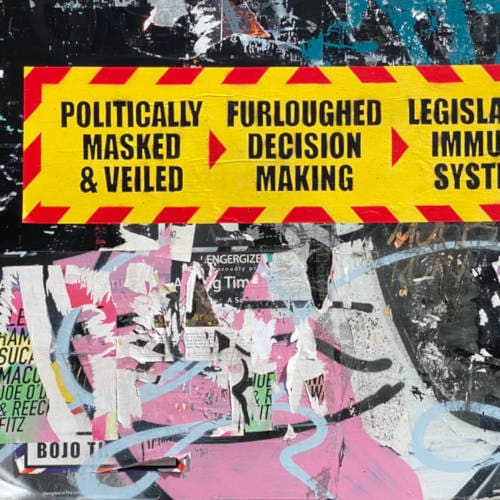

Featured image by John Cameron on Unsplash.