In They Eat Our Sweat, Daniel Agbiboa engages the road transport sector in Lagos, Nigeria, to reveal how corruption operates through a dialectical “double capture” of state and society. Ethnographic encounters in the bustle and bottleneck of urban thoroughfares expose the precarity of informal transport workers who operate minibuses and drive motorbike taxis. Their everyday survival demands acts of petty corruption: bribery, fraud, and patronage. Daily confrontations with transport associations and unions, such as the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW), law enforcement agents, and government officials ensure endemic compliance with their extractive practices. Simultaneously, these intermediaries entangle street-level with state-level corruption. The latter includes extortion, embezzlement, and grafts characteristic of grand corruption in a political economy dominated by trickle and surge of oil wealth.

In They Eat Our Sweat, Daniel Agbiboa engages the road transport sector in Lagos, Nigeria, to reveal how corruption operates through a dialectical “double capture” of state and society. Ethnographic encounters in the bustle and bottleneck of urban thoroughfares expose the precarity of informal transport workers who operate minibuses and drive motorbike taxis. Their everyday survival demands acts of petty corruption: bribery, fraud, and patronage. Daily confrontations with transport associations and unions, such as the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW), law enforcement agents, and government officials ensure endemic compliance with their extractive practices. Simultaneously, these intermediaries entangle street-level with state-level corruption. The latter includes extortion, embezzlement, and grafts characteristic of grand corruption in a political economy dominated by trickle and surge of oil wealth.

Documenting the inseparability of petty and grand forms of corruption allows the book to transcend a standard celebratory evaluation of the informal economy and its praise of entrepreneurial actors. Instead, the book offers a sobering account of paired predation. Indeed, personal and archival accounts support new analytical approaches attentive to the “mutuality” of corruption. Corruption is perpetrated not just by government officials who exploit public office for private gain. It is also deployed by citizens who might criticise corruption but are complicit in its perpetuation for daily survival. Yet, “the logic of mutuality has yet to penetrate the existent literature on corruption in Africa” (Agbiboa 2020: 16). Without reservation, this book corrects the chronic myopia in development literature that sees the state as the source and solution of corruption, while obscuring the role of ordinary citizens.

By collapsing the supposed distance between street- and state-level corruption, Agbiboa joins the ranks of anthropologists, such as Daniel Jordan Smith (2010, 2022) in demonstrating two key points about corruption in Africa. First, average citizens may not be the willing accomplices of corruption but are wilful in their participation. Repeatedly, the stakes of refusal trump moral condemnation. Second, the paradox of supposed “weak states” is laid bare. Corruption strengthens rather than undermines state power. Here, informalization is often mis-characterised. Perceived as the state’s retreat from ordinary citizens, informalization represents a mode of recruitment by the state to further entrench corruption in everyday lives.

Agbiboa’s investigation into the mutuality of corruption between state and society picks up where Daniel Jordan Smith left off in his seminal account. In “Culture of Corruption,” Smith addresses the discursive and narrative aspects of “Nigerians’ experiences and understandings of the state,” (201: 15) rather than the state per se. Moreover, Smith traces the downward and outward siphoning of money to fulfil kin and community obligations by those in positions of relative power. Conversely, Agbiboa traces the upward distribution of financial flows. Money moves up a chain of collusion. To illustrate, drivers “settle” motor park touts (abgeros). They, in turn, pool the money to pay-out association chairmen. Then, money lines the pockets of local politicians and police chiefs. Trapped in inexhaustible circuits, the multiple practices of state actors and informal workers highlight the banality rather than the exceptionality of corruption. Consequently, readers will appreciate this portrayal of state corruption inhabited by identifiable actors and dirtied hands, as opposed to shadowy figures of political power. Overall, these tentacled transactions show how money greases everyday access, protection, and mobility on Lagos’ roads.

Agbiboa’s investigation into the mutuality of corruption between state and society picks up where Daniel Jordan Smith left off in his seminal account.

Together, these accounts deepen our collective knowledge of corruption in practice and in excess of the Weberian bureaucratic ideal for how modern democracies ought to function. However, a position that contests the abstract neutrality is not an immediate appeal to human relationality. Agbiboa writes against what he perceives to be an over-prioritisation of neo-patrimonialism in studies of corruption within international development studies, political science, and economics. These disciplinary defaults to essentialist, culturalist, and functionalist rationalisations curtail more fruitful explanations. In contrast, the book advocates for anthropological approaches that eschew definitive distinctions between state and society, much like the misleading divisions between formality and informality, or illegality and legality. To assert that distinctions are overdrawn is not equivalent to stating differences do not exist. A critical message from the book is that people’s relationship with them are inconsistent, rather than deterministic.

The uncomfortable colonial inheritance of political structures, bureaucratic ideologies, and legal frameworks invites studies of actual order and operation in Africa. Shifting the scholarly gaze “from government to governance in the developing world” (Agbiboa 2020: 23), the author explains how statist aspirations can paradoxically escalate both precarity and corruption. For example, the transformation of Lagos into a “global city” foremost involved purging informal workers from its environs under the aegis of law and order. Conversely, informal workers also sought legal recourse. Drivers and associations took Lagos State government to court to claim their collective ‘right to the city’. Underscoring ordinary people and elites’ use of the legal system challenges prevailing analysis that enshrines African nations as lawless or outside of the law. In a similar vein, Samuel Fury Childs Daly (2020) provides an account of law and crime during the Biafra-Nigeria civil war. Daly attributes fraud, duplicity, and forgery–the polysemic grammar of corruption–to the constellation of “martial skills” (Daly 2020) necessary for survival. Whereas Biafra disappeared in the aftermath of war, these “skills,” on the other hand, outlasted their rogue purpose. Fraud for survival was thereafter criminalised in favour of reconciliation and order. What is clear, however, is that malfeasance is enabled through intimacy with the ‘proper’ functions of bureaucracy and legality, rather than its removal. Intriguingly, today’s mutuality of corruption features as a distant and distorted artefact of these wartime tactics. Incorporating the antecedents of law and crime could strengthen the book’s argument against neopatrimonialism and its essentialising tendencies.

They Eat Our Sweat ably demonstrates the generative capacity of corruption to reproduce its own conditions of survival.

This book shares with scholars the unexamined assumption gleaned from informants that corruption hinders development and prosperity. A recent study by Yuen Yuen Ang (2020) on China challenges conventional wisdom that corruption hampers growth. One limitation of mutuality is that it rehashes the ideological mood of Africa’s corruption as generative of replicating daily life, but ineffective for growth and rather corrosive on development. Yet, Ang (2020) presents China’s nexus of corruption and capitalism as exponentially productive. This commentary is not a call for comparative work but an invitation to avoid reifying Africa as “all that is incomplete, mutilated, and unfinished, its history reduced to a series of setbacks…” (Mbembe 2001: 1). For instance, Nigeria and China are near neighbours on the annual Corruption Perception Index, collected by Transparency International (Ang 2020). Why then, is China corrupt and rich, but Nigeria is corrupt and poor? Africa’s continued exceptionalism can also be a shortcoming in the appraisal of corruption. Integrating its myriad varieties, such as grand and petty corruption, increases the richness of accounts but might also sacrifice analytical specificity. It also strikes at whether corruption ought to be the dominant window on African governance. Nonetheless, the book’s strength is to entice the reader to learn more about how corruption actually works. If China is an outlier in the productivity of its corruption, it is also an analytical lodestar worthy of comparative contemplation. They Eat Our Sweat ably demonstrates the generative capacity of corruption to reproduce its own conditions of survival. What remains unanswered is the effect of corruption on economic growth and development. What can the specificity of corruption in various predatory states reveal if poverty is not inevitable? If corruption is the critical barrier to wealth in Nigeria, what might be learned from “the paradox of prosperity and corruption” in China (Ang 2020: 20)?

Deploying mobile ethnography – moving with people on the go – befits an ethnography of transport. It allows Agbiboa to “experience firsthand the violent and shifting mutualities between law enforcement agents, transport unionists, and mobile individuals” (Agbiboa 2020: 34). A fast pace of prose mimics the urgency of urban life. The reader joins passengers in the sticky heat of crammed buses as they lurch and loiter along the road. The palpable danger of transport work is weaved into the analysis with skilful restraint to avoid descending into a genre of suffering so prolific in studies of survival in the global south.

The reader joins passengers in the sticky heat of crammed buses as they lurch and loiter along the road.

In Lagos, it is a given that everyone is involved in corruption. Few people, however, wish to speak of their own involvement. A proxy method of an “alienation effect” (Agbiboa 2020: 40) is used to elicit depersonalised evaluations of other’s corrupt behaviours. But it leaves the reader wondering how prone such a method is to exaggeration of the distance between evaluation and action. While not limited to this study, but a perennial concern, when people implicate others but excuse themselves. Agbiboa asserts that performance itself is telling. However, we remain unsure of what it purports to expose. Moreover, it has the unintended effect of accentuating a polarised moral valence, as people gleefully highlight the shortcomings of the government while accentuating their own vulnerabilities and struggles.

This book is part of a series to advance theory in international development studies. As such, it targets practitioners, policy makers, scholars and students of a discipline steeped in a pedagogy that views the state as the sole architect of corruption. Furthermore, its patent rejection that corruption in Africa is “sui generis and an indigenous pathology” (Abigboa 2020: 207) encourages and emboldens new interpretations. For anthropologists, however, the arguments in this book are familiar. For this reason, it is a boon to the discipline. The paradox of “criticism and complicity” (Abigboa 2020: 2) is an adept ‘translation’ of anthropology’s canonical ideas of cultural coproduction.

References:

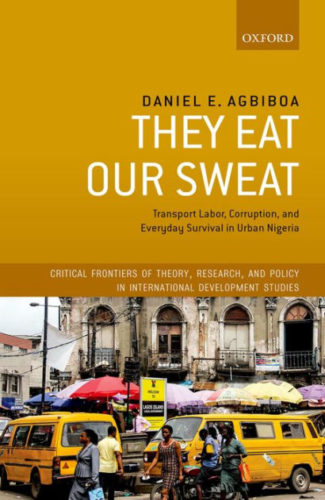

Agbiboa, Daniel E. 2022. They eat our sweat: Transport labor, Corruption, and Everyday Survival in Urban Nigeria. Oxford University Press.

Ang, Yuen Yuen. 2020. China’s Gilded Age: The Paradox of Economic Boom and Vast Corruption. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Daly, Samuel Fury Childs. 2020. A History of the Republic of Biafra: Law, Crime, and the Nigerian Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mbembe, Achille. 2001. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Smith, Daniel Jordan. 2010. A Culture of Corruption: Everyday Deception and Popular Discontent in Nigeria. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Smith, Daniel Jordan. 2022. Every Household Its Own Government: Improvised Infrastructure, Entrepreneurial Citizens, and the State in Nigeria. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Featured picture by Michal Osmenda, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.