“Lena, you can turn on the camera now.” The view of the space station changes from monitor to film image. The opening scene of Andrei Ujică’s film Out of the Present (1997) narrates the arrival of a 35 mm film camera at space station Mir. To the best of our knowledge, this camera is still orbiting Earth (Zielinski 2006: 2). However, Mir, as its original destination and temporary home, is no longer in orbit. The station burst into pieces over the South Pacific Ocean after re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere in 2001. There are other remains of Mir though. The cosmonauts took almost three hundred hours of video footage and sent the tapes back to Earth. Ujică used this footage to tell the story of Sergei Krikalev: the cosmonaut and flight engineer who started his mission in 1991 from the Soviet Union and landed ten months later in independent Kazakhstan. In this article, I explore the representation of Mir in Ujică’s film in order to think through the infrastructure of outer space. I argue that his use of past cinematographic records challenges the understanding of infrastructure as fixed in space-time.

Archives exert a strong gravitational pull on those caught in their orbits.

After Ujică got hold of the cosmonauts’ video, he shut himself up in his apartment in Moscow. The tapes are most extraordinary, belonging to the rare category of objects that have travelled from Earth into space and back again. Moreover, they hold nothing less than the cinematic record of seeing Earth from space. Ujică’s immersion in the images created a peculiar sensation: “I had the feeling I was experiencing the flight myself and arrived at the realization that being in space had something elemental about it” (Ujică and Virilio 2003: 62). The sensation of being in space by force of these images must have been very powerful. Ujică kept this detachment from Earth in check by bringing the emerging Out of the Present into conversation with the two most influential science-fiction films of the twentieth century: Stanley Kubrik’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972). Science fiction became his only attachment to the world outside the archive (Ujică and Virilio 2003: 69).

Out of the Present directs our gaze firmly towards Earth – as do Blue Marble and Earthrise, the iconic images produced from Apollo photographs. But Ujică’s view of Earth from space is different. This is no longer the famous “god trick” (Haraway 1988) of a disembodied and transcendent gaze from nowhere. Rather, it comes from a hazard-prone metallic insectoid creature with solar panels for wings, marking the apogee of Soviet scientific-technological progress, which hosted humans dubbed cosmonauts by virtue of their ability to survive in outer space.

Through the eye of the camera, we experience the cosmonauts’ continuous search for Earth-born(e) spatial orientation and share their vertiginous feelings when looking at Earth from outside the space station.

The camera presents us with a view far enough from Earth’s surface to see its curvature, the thin layer of the atmosphere and the stunning shifts between land, sea and clouds. But not far enough to do away with the feeling of unease about what is going on “down there” at this moment.

Down on Earth, Mir’s superstructure is about to collapse. Halfway through the film, a sudden cut takes us from outer space to Earth. It catapults the viewer into the events of August 1991 in Moscow – tanks, crowds, shouting and high anxiety. Only the solitary figure of an artist sits quietly in the street, painting the revolution unfolding before his eyes. He mirrors the eerie calm of the space station, travelling from horizon to horizon above the events.

The panoptic view from Mir puts the turmoil in Moscow into perspective – the scope is planetary rather than terrestrial.

Earlier on, Out of the Present narrates the phone call the cosmonauts receive from the president. The switchboard operator confirms that this is Moscow speaking, and announces that Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev is on the line. “What are you doing just now?” asks Gorbachev. The crew answers: “We are getting ready for dinner.” Gorbachev laughs and answers: “Oh, if it were a little later, we could have dinner together!” The distance of space allows for a paradoxical intimacy, perhaps creating for Gorbachev a momentary escape from Earth in troubled times.

Mir is not just an outpost of humanity, but also a periphery of Moscow as the center of Soviet power. A military command structure and thin lifeline connects Mir to the spaceport at Baikonur. Formerly leased from the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic by the Soviet Ministry of Defense, Baikonur became part of newly independent Kazakhstan following the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991. Soon after, the Kazakh government began to lay claims to the spaceport, which remained under Russian control. To accommodate Kazakhstan, the Russian flight direction at Baikonur decided to alter the composition of the relief crew for flight engineer Sergei Krikalev and his colleague. They replaced the scheduled Russian flight engineer with research scientist Toktar Aubakirov, the first ethnic Kazakh in space. Tensions arise in Out of the Present when Aubakirov is seen playfully enjoying microgravity with a toy airplane while his colleagues carry out scientific experiments. After a few days, he is ordered to return to Baikonur on the flight scheduled for the relieved crew. Krikalev, however, has to stay on Mir and continue his duties as flight engineer for another six months. Thus, political dealing to secure continued rights to launch from Baikonur clashed with Mir’s requirements for technical expertise.

Mir as infrastructure is also in a state of revolution, albeit of a different character.

The space station rushes around Earth in a relentless cycle, passing Baikonur every 92 minutes. The viewer is able to sense this time span, as the film’s length matches the duration of one complete orbit. Repetition based on physical laws creates its own temporal regime, utterly at odds with the biological rhythm of humans. Life on Mir thus follows the Earth clock. More precisely, it follows Moscow’s clock – the Soviet empire of time expands into space. Through images of landscapes, Out of the Present narrates the change of the seasons on Earth in stark contrast to the absence of any seasonality on Mir itself. These superimposed temporalities subvert orientation in space and time on Mir by suspending earthly frames of reference. Fixes for this blankness include not only the retention of a strict 24-hour schedule, but also the creation of accustomed points of orientation through light and color to simulate floor and ceiling (Ujică and Krikalev 2003: 48). Thereby, the alienation of cosmonauts from their accustomed diurnal and seasonal round is contained within the walls of Mir, provided that they resist the temptation of looking out of the porthole.

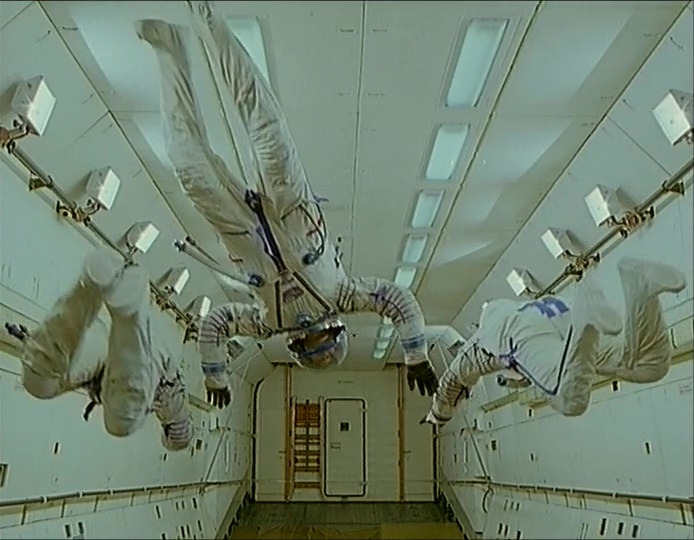

The microgravity environment of Mir creates the experience of weightlessness. Out of the Present embodies this experience: images of weightless cosmonauts taken by a weightless camera. The cosmonauts’ movements in microgravity lose their habitual angularity, becoming smooth and continuous. Their floating bodies appear abstract and insubstantial, contained only by Mir’s metallic hull. Yet when Krikalev is shown working out strapped to a treadmill, his body becomes familiar again. The movements of running, the play of his muscles and the sweating render it earthly in an erotic way.

Actual Earthfall is harsh though. As viewers, we brace ourselves for impact when the charred capsule hanging from a parachute falls out of the sky.

It hits Earth’s surface like a meteorite, leaving a small crater on the arid Kazakh steppe. The helpless cosmonauts have to be lifted out of the capsule, weak, dizzy from descent and struggling to cope with Earth’s gravity. Becoming Earthbound again is a punishing experience.

The Russian word mir is polysemous, translating as ‘“world,” “Earth” and “peace.” In Out of the Present, space station Mir becomes the world – a crowded and cluttered space enfolded by the vast reaches of the Universe, to which newcomers are greeted ritually with bread and salt in the Russian tradition. Yet Mir is also Earth’s companion: it is subject to the latter’s gravitational pull, and its matter is carved out of Earth’s body like the moon billions of years ago. By orbiting, Mir exerts the tiniest bit of gravity of its own on the home planet, yet both infrastructure and cosmonauts age marginally slower than they would on Earth. While all directions are experienced as equal in space, the direction towards Earth represents the emotional and epistemic axis for cosmonauts on Mir. In the absence of terrestrial places of history and attachment, Earth as a whole becomes the frame of reference and embodiment of “our home” (Ujică and Krikalev 2003: 49).

Ujică’s work presents an apparent contradiction: Out of the Present is a documentary science-fiction film, with a riff on conventional understandings of the genre through repeated docking scenes. Ujică narrates Mir in powerful analogy to Tarkovsky’s space station hovering above Solaris’s planetary sea, of which the many cinematic allusions to Solaris are suggestive. The unfathomable Earth sends traumatic memories to Mir, and its inhabitants struggle to make sense of and reconcile these memories with their current condition of existence. At times, they withdraw in joyful regression to childlike play in weightlessness, or stare at Earth through the porthole, transfixed and mesmerized. Yet they also emit cinematographic memories of their struggle back to Earth. By virtue of these memories from the past, the Mir of Out of the Present is an impossible (and yet very real) present. Because of this paradoxical condition, Mir becomes an object of representation that is nonimaginary and yet cognitively estranging (Chu 2010). As cinematographic infrastructure, Mir creates estrangement by subverting our habitual attempts to fix objects in space-time – a taken-for-granted earthly practice that tries to make sense of the world.

“Is the camera still rolling?”

“Yes.”

“All right, let it roll.”

References

Chu, Seo-Young. 2012. Do Metaphors Dream of Literal Sheep? A Science-Fictional Theory of Representation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–99.

Kubrik, Stanley. 1968. 2001: A Space Odyssey. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (film).

Tarkovsky, Andrei. 1972. Solaris. Mosfilm (film).

Ujică, Andrei and Sergei Krikalev. 2003. “Toward the End of Gravity I”, transl. by Sara Ogger. Grey Room 10 (Winter 2003): 46–57.

Ujică, Andrei and Paul Virilio. 2003. “Toward the End of Gravity II”, transl. by Sara Ogger and Branden W. Joseph. Grey Room 10 (Winter 2003): 58–75.

Ujică, Andrei. 1997. Out of the Present. absolutMedien (film).

Zielinski, Siegfried. 2006. Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

To peruse all issues of Roadsides, visit the journal’s website: https://roadsides.net