“Why does it matter if Raia is at home or not?”, the clinic’s flat-manager wondered. “It’s not her apartment but the clinic’s”, she said with a forced smile, and it was strictly forbidden to take pictures of “their” surrogates anyway. As such, it was handy for her that Raia Dimitrovna had medical examinations and would be out on the day the manager had proposed for our photo session. She would be accompanying us, watching our every move, making sure the photographer and I only documented the apartments and the objects in them. And she would be answering all our questions in Raia’s absence. Yes, including any about the surrogate’s personal belongings.

There was an uneasy irony to this situation, for it was precisely the topic of absence that interested the photographer Sarah Hildebrand. Sarah had come to visit me during my fieldwork time at the Altra Vita IVF-Clinic in Moscow to take pictures for our book project hope. The book would narrate the stories of people who crossed emotional, corporeal and geographical boundaries in the hope of finding a better life. Sarah’s photos sought to reflect the traces of these people, while they themselves should not appear on the pictures. It was the presence of an absence the photographer was intrigued by. But we did not want to enter Raia’s flat without her being there. It would have felt like an act of violence, like an intrusion into her private space, despite the approval she had given me and despite the word of caution she had added to this approval:

We would not be able to capture any traces of her in the photographs, Raia had said. Her soul (dusha) was not here, not in this apartment.

Not even in Moscow.

Raia had moved to the capital after life in her hometown, Donetsk, had become too dangerous. The military conflict between Russia and Ukraine in early 2014 had led to several bombings of towns and cities in Eastern Ukraine. Raia had left her family, her flat, her job and her car, and had fled to Moscow to work in one of the many infertility clinics, to carry a child for an unknown couple. She would earn one million roubles for her service as a surrogate – an amount with which she could resettle in the south of Russia and build a secure existence for herself and her five-year-old daughter. She was hoping to buy a flat, so she could have a place “of her own”, as she stressed; a new home, a home that reflected her traces, her soul. The apartment in Moscow was just a temporary home for nine months, for the time of her pregnancy, just as Raia’s womb was a temporary home – or a “little house” (domchik), as some of the surrogates said – for the child she was carrying.

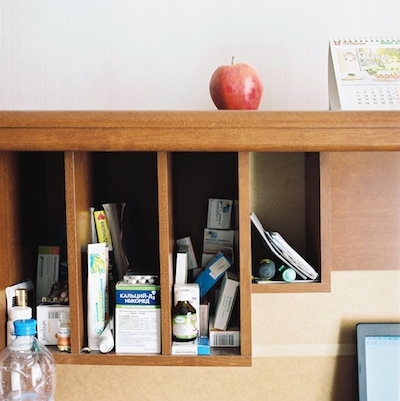

On the afternoon of the photo session, the manager offered us to visit Daria Borisova’s rather than Raia’s flat, as the former would be at home. When we arrived Daria was in the middle of preparing the meat for her dinner. The manager told her to stay in the kitchen and nudged us into the room that functioned as living room and bedroom alike. I had been to this flat a couple of times before, to drink tea and chat with Daria. But being here with Sarah, and being attentive to the traces changed the way I perceived and experienced this space. While Sarah put up the tripod for her Hasselblad, my gaze wandered from the desk with the open laptop, over the remote control lying on one of the pulled-out sofa-beds, the shelf containing the hormonal medication Daria had to take, another shelf with various cosmetic items and an embroidered icon of a saint, to the curtain through which I could vaguely see the birch trees in the yard. The many textile and wallpaper patterns in the room made me feel dizzy.

The manager and Daria, who briefly joined us to inspect the unusual camera, were amused by our “boring” motives.

But for Sarah, as photographer, and for me, as anthropologist, it was precisely the unspectacular and the ordinary that attracted us, that had the potential to tell bigger stories.

One of the objects that caught our attention was a fan. Wrapped in transparent foil and tucked away behind an ironing board, the fan seemed to mirror the standardisation and anonymity of these clinic flats – flats that were all similarly arranged, whose furniture and equipment had little to do with their inhabitants. The few personal belongings that the surrogates brought to Moscow did not fill up the space. The walls were mostly empty but for the occasional painting or laminated sheet of flat instructions the manager must have put up. Raia was right, I thought. These flats were in a decent condition but they did not feel like a “home”; they had no soul. Sarah’s photographs not only captured the traces that people left but also the difficulty of leaving traces in a place that was not meant to be home to these traces.

The wrapped fan can also be read as a symbol for the anonymity and standardisation of the surrogacy programmes themselves. Like Raia and Daria, most surrogates I met during my fieldwork in Moscow did not know the couples whose children they were carrying. As infertility and surrogacy were highly stigmatised issues and belonged to the sphere of secrecy, many welcomed the opportunity to temporarily move from their towns to the big and anonymous city of Moscow to hide their growing bellies. “I have found work as a babysitter” or “as a maid”: this is the story the women told their neighbours, friends and family, the story Daria had told her parents and her son, whom she had not seen in six months. She was also hoping to provide her family with a home of their own after the surrogacy; but she did not want anybody to know how she had earned this money.

Moscow’s size and anonymity were also reasons why many surrogates disliked the city. While Raia was grateful for a temporary refuge, she also felt lonely most of the time. The fact that she had no friends in Moscow, that she worried about getting lost in the noisy and congested streets, and that she was afraid of sudden complications concerning the pregnancy bound her to the surroundings of the clinic and to the everyday dullness of pregnant waiting.

The flat was relief and confinement at the same time.

From the clinic’s perspective, the flats provided an opportunity for increased control. They perceived the surrogate body as dangerous, for a poor pregnant woman was imagined to be unpredictable: not only was she full of hormones but she could also make use of her powerful position as child-bearer in order to bribe the clinic or the intended parents. A common way of preventing such potential abuse was to inhibit direct contact between the two parties, between the surrogates and the intended parents. This further promoted anonymous and standardised all-inclusive programmes that were mediated and overseen by surrogacy agencies and clinics. Their measures of control took many forms. Raia and Daria both had to expect surprise visits from the manager, who would check on cleanliness or fridge contents, among other things. The control visits decreased after surveillance cameras were installed in the entrance halls of all flats. The clinic hoped to discipline the women’s bodies by regulating their movements in and out of the flats. The women were not supposed to stay out late, not allowed to welcome men, and even female visitors – like me – sometimes aroused suspicion.

I could not help but notice the contradictory ways in which privacy was evaluated in the field of surrogacy.

On the one hand, many surrogates had to subject themselves to a form of control that severely intruded into their private sphere. On the other hand, I was often denied access to this field with the argument that it was unethical to do ethnographic research on such a delicate and hidden issue. Knowledge about surrogacy should be protected, not shared, and my scholarly interest was devalued as improper “nosiness” (lyubopitstvo). Lack of trust was a big issue for many of my research participants and it was this aspect I brought up in my conversation with Daria and the manager on the afternoon of the photo session. After realising that the photographer needed more time than expected, the two women had lost interest in controlling her moves. While Sarah was hovering around in the kitchen, they started questioning me about the differences between life in Russia and life in “Europe” (which, to them, clearly did not include Russia). Russian people had witnessed too much corruption and fraud to trust each other, the manager said. “Where you are from, people are quickly called ‘friends’. But not here. Here, ‘friends’ are basically part of the family.” Family was also what she found among her colleagues at work, she continued, after moving from Belorussia to Moscow. In her case, the clinic had succeeded in creating a place she could call home.

At the end of the day the manager seemed to have understood what Sarah and I were hoping to find in the surrogates’ flats. When leaving Daria’s flat after two hours, she offered us to stop by another apartment. A surrogate just moved out this very morning – “We might still be able to feel her presence despite her absence.”

—

A shorter version of this article, titled “Meine Seele ist nicht hier”, was published in German on Anthroblog, Institut für Sozialanthropologie (4/ 2018).

—

The photo and text book “hope” was published with Christoph Merian (Basel, Switzerland) in March 2018. The three chapters of the publication explore surrogacy in Russia, liver transplantation in Germany as well as migration and death in the Spanish–Moroccan borderlands. The book resulted from the collaboration between photographer Sarah Hildebrand and the social anthropologists Gerhild Perl, Julia Rehsmann und Veronika Siegl.

Featured image by Sarah Hildebrand.