As if he was, for the occasion of Halloween, joyfully embracing the figure of the grotesque, Hubert Aiwanger, former as well as designated minister of the economy in the Free State of Bavaria, went on record on public radio on October 31st, to denounce recent public demonstrations throughout Germany as antisemitic and critical or hostile towards Israel. Performing as a heroic member of a chorus of the brave to finally speak out loud what had too long been silenced (yet, in fact, spoken about ad nauseum), he repeated the well-rehearsed trope that anti-Semitism had been imported to Germany and that migration policies of the last years were to blame for these worrisome developments. Germany was handing ‘our passports’ to these people who then went to the streets to attack the police, attack Israel, and attack shops. In case his listeners had forgotten, his words thereby served as a reminder of what was to count and matter as sacred elements of Germany’s raison d’état: security forces as embodiment of the state, capital, and Israel as fetishised embodiment of – as well as limits to – Germany’s atonement for past genocidal crimes. Unsurprisingly for any right-populist politician of moderate ambition, his demands were equally predictable: restriction of immigration and stricter policies of deportation.

The obscenity of this statement was not missed on social media. Aiwanger had been at the centre of a scandal, indeed a tectonic shift in German domestic politics, several weeks prior. Ahead of the regional elections, a national newspaper had revealed that Aiwanger had carried, and most likely authored, a most vile anti-Semitic pamphlet in his school days. While his brother came out in an attempt to rescue his innocence by taking the blame upon himself, the allegations continued and expanded to Aiwanger practicing speeches by Hitler-him-very-self in front of the mirror and other horrific details. In populist manner, he toured Bavaria’s beer tents declaring himself the victim of a left-driven witch hunt ahead of the elections. Bavaria’s prime minister Söder of the Christian Social Union (CSU) eventually backed him up. Aiwanger’s party was able to expand its share of electoral votes by about 4% and will continue to govern in a coalition with the CSU.

Anti-Semitism, so we learn in 2023, is permissible when committed by a Bavarian white man.

It should have been the end of Aiwanger’s political career and, indeed, about ten years ago, the fact that it wasn’t would have been utterly unimaginable. He would have had to step down. What we witnessed in late summer was a tectonic shift of the terms of domestic politics. Aiwanger excused himself, i.e. the act of carrying the pamphlets in his school bag, something he could not deny, by declaring it a sin of his youth. Anti-Semitism, so we learn in 2023, is permissible when committed by a Bavarian white man. We learn that it is nothing more than a coming-of-age confusion. In fact, it is not anti-Semitism at all, but an unfounded witch-hunt by a left-liberal media elite bent on destroying this politician’s career.

But there is more to this tectonic shift: quieter, more marginal scenes. In late September, the local branch of the Christian Democratic Party (CDU) in eastern Westphalia joined electoral forces with the extreme right-wing AfD to scrap the funding that had been demanded, promised, and allocated for the long-term financing of a National Socialist prisoner of war camp memorial site in Stukenbrock-Senne near Bielefeld. This has followed a number of other instances where the CDU, as one of Germany’s major parties, has succeeded to push political decisions by more or less tacitly relying on the votes of the party most closely acting as a revenant of the Nazi-era NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ Party). Their quiet co-operation now extends towards the sphere of memorial politics.

No, in the name of Germany’s responsibility for the past, [our] energies must be routed, we are told, towards the condemnation not only of Hamas, but of people who are claiming and exercising their democratic right to protest against Israel’s war crimes.

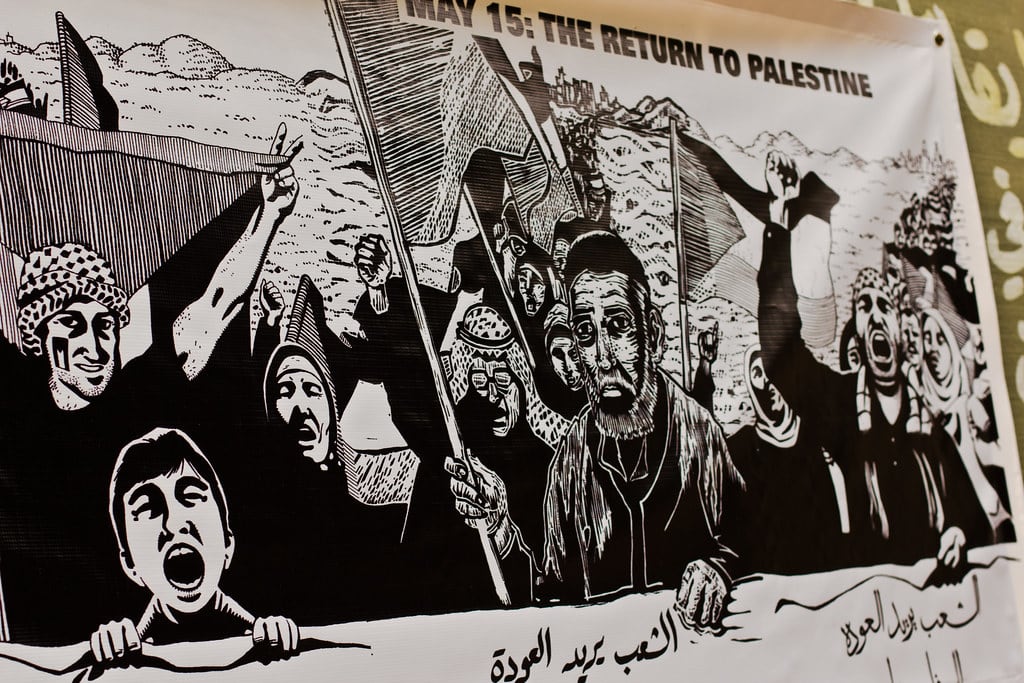

But yet, in this day and age where politics is being reduced to the incessant call for and the repeated performances of condemnation, our energies of condemnation are not even channelled towards Aiwanger and all those who allow him to spurt his unbearable nonsense on public radio. No, in the name of Germany’s responsibility for the past, these energies must be routed, we are told, towards the condemnation not only of Hamas, but of people who are claiming and exercising their democratic right to protest against Israel’s war crimes. This happens as these war crimes are openly backed by the German federal government which could not even bring itself to vote in favour of a UN resolution demanding a humanitarian ceasefire because, as the German foreign minister explained, Hamas’s terrorist crimes had not been condemned enough. All this in the name of the Holocaust.

This degree of historical perversion, or indeed irony, demands levels of political, mental, emotional, and ethical contortionism that are testing our limits of the possible. While the very real anti-Semitism of political leaders is reduced to the irrelevant status of childish games, the conservative party is joining forces with the harbinger of twenty-first century fascism in order to prevent the institutionalisation of a Nazi memorial site. Meanwhile, ‘responsibility for the past’ has been evacuated to the ethically and politically hollow gesture of ‘unconditional’ solidarity with a state whose officials have left no doubt that they are determined to disregard international law and kill thousands of civilians in their eliminationist drive for revenge. I so very much agree with Michael Rothberg and Candice Breitz, who had planned a conference on (responses to) the entangled histories of violence under the title: We still need to talk. We need to defend and craft a political space of debate and analysis that is not entirely colonised by demands and gestures of condemnation (and accusation), but that allows us to not lose sight of the tectonic shifts that take place in the shadow of the glaring violence of killings, kidnappings, and bombs. Yet, irony reigns: the Federal Agency for Civic Education, a child of that post-war political order of ‘never again’ and whose very responsibility it is to support and facilitate public debate, has decided to cancel its funding and support for the conference. The lesson of Germany’s past in 2023? We shall no longer talk. Only condemn.