Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the science of masks has become hotly debated by epidemiologists, public health officials, and the public at large. The possible positive effects of masking the general public has been a particularly contested subject.

Having previously tried to dissuade the general public from wearing masks, the European and the United States Centres for Disease Control started recommending the use of cloth face coverings in early April. The World Health Organisation followed suit on the 6th of June, recommending medical-grade masks for healthcare professionals, caretakers and the sick, and ‘three-layered fabric masks’ for the public. The political response to the expert advice has also varied across the globe. In countries with an established tradition of mask- wearing, such as South Korea and Taiwan, public health authorities quickly recommended citizens cover their nose and mouth when out in public. For most Europeans, however, masking has accompanied the lifting of quarantine measures. In Austria, Germany, Poland, France, and the United Kingdom, fabric face coverings are now mandatory on public transport, in schools, and in retail spaces.

Discussions about how, when, and whether to mask the public are not as novel as they might seem.

Discussions about how, when, and whether to mask the public are not as novel as they might seem. Face masks have been used by medical professionals since the 16th century, initially for purposes of personal protection and later also to prevent cross-contamination between patients (Spooner 1967). The idea they be might be used by the general public, however, was first introduced with the advent of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. That year, a number of cities in the United States issued legislation – known as the ‘mask order’ – requiring all citizens to cover their faces in public places (Crosby 2003, Blakely 2006). The order was met with widespread protests and civil disobedience, citizens flaunting the order by refusing to wear masks or deliberately wearing them improperly. The wearing of masks was also recommended in the United Kingdom (Loeb 2005) and in Japan, where the National Public Health Bureau encouraged masking on public transport, as well as in theatres, cinemas, and other places of entertainment (Burgess and Horii, 2012). While the ‘mask order’ was met with resistance by the American public, the recommendation was more positively received by the Japanese public who came to see mask-wearing as ‘the embodiment and the symbol of national defence against the invisible threat of the influenza’ (Horii 2014).

Despite lacking any precedent, citizens in the Czech and Slovak Republics widely accepted a legal requirement to cover ones’ nose and mouth as part of nation-wide lockdowns in both countries in March.

Public reactions to contemporary masking orders have been similarly varied. Despite lacking any precedent, citizens in the Czech and Slovak Republics. widely accepted a legal requirement to cover ones’ nose and mouth as part of nation-wide lockdowns in both countries in March. Indeed, the Czech masking order was followed by a grass roots mobilization of citizens voluntarily producing and distributing fabric masks for medical personnel, frontline workers, and fellow citizens unable to make their own. Wearing a mask became a visible sign of participation in a collective effort to combat the virus, helping to strengthen the national community inwardly and defined it outwardly. In contrast, masking orders have been met with ambivalence, or even resistance in other countries. In the United States, face masks have become a point of contention amongst cititzens demonstrating against lockdown measures and the subject of partisan arguments about the balance between individual liberty and collective responsibility. Protesters in Texas and Virginia have been photographed brandishing signs painted with the pro-choice slogan ‘My Body, My Choice’ and crossed-out pictures of surgical masks. Others have linked masking orders to communism, citing a perceived constitutional right to freely choose whether or not to cover up.

Accross Europe, masking orders have also sparked debates about the nature and limits of liberal citizenship. Despite lacking any cultural precedent, the legal requirement to cover ones’ nose and mouth has been widely accepted by citizens in the Czech and Slovak Republics. Sociologist Michal Vašečka has speculated that such conformism may be a legacy of the collectivism of the Communist past. In France, governement officials were initially reluctatn to mandate the wearing of masks in public space. A ban on Islamic face veils (niqab) in 2011 and of face masks at public demonstrations in 2019, cemented a cultural and legal imperative that citizens uncover their face in public sphere. Adopting face masks, the French anthropologist Frédéric Keck has argued, would not merely be contrary to existing cultural practice, but would require a ‘revolution of civility’. Interestingly, both Keck and Vašečka see these divergent reactions as grounded not merely in cultural differences between Slovakia and France, but in a differential embrace of liberal notions of sovereignty and bodily autonomy. Invoking ideas of (Communist) collectivism and (Enlightenment) civic virtues, they frame masking as incompatible not so much with local traditions of medical practice or social comportment, but with the exercise of liberal citizenship itself.

Invoking ideas of (Communist) collectivism and (Enlightenment) civic virtues, they frame masking as incompatible not so much with local traditions of medical practice or social comportment, but with the exercise of liberal citizenship itself.

Whatever assumptions about the incompatibility of face masks and liberal citizenship, however, much of Europe – France included – now seems to be experiencing Keck’s ‘revolution of civility’. Recognizing the possible public prejudice against covering up, politicians and public health authorities across the continent have framed mask-wearing as a pro-social, other-oriented practice, rather than a personal protective measure. Presenting masking as part of the performance of responsible citizenship, they have encouraged individuals to feel responsible not only for their own health, but also that of their fellow citizens. Others have made deliberate efforts to present masks as fashionable – and fashionably patriotic. In the Slovak Republic, the public has been encouraged to share pictures of themselves in masks with the hashtags #ruskoniejehanba (#amaskisnotembarrassing) and #ruskotipristane (#amasksuitsyou). President Zuzanna Čaputová attends official events wearing colourful cloth masks and gloves which match her outfits, and Prime minister Igor Matovič briefs the press in white masks decorated with a small Slovak flag. Facemasks in the colours of the national flag also appear on Italian public health notices, and are regularly used by Italian politicians.

Such political performances mark out practices of masking as part of a wider moral imperative to protect the greater good. However, they also work to define the content and boundaries of this greater good in the form of the national body politic, symbolically reinforcing both postive notions of national solidarity and negative forms of nativism which have led migrant workers and foreign students to be stimgatized as carriers of the disea.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, however, face masks have also performed a particular kind of boundary work; demarcating and negotiating the relationship between the body and the body politic, and the individual citizen and the national whole. They have become practically and symbolically entangled in the (re-)production of power in public space, reinforcing political choices and giving them a visual and material presence in society.

Masks are boundary objects (Fox 2011), mediating between ideas of contamination and containment, purity and pollution, and life and death. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, however, face masks have also performed a particular kind of boundary work; demarcating and negotiating the relationship between the body and the body politic, and the individual citizen and the national whole. They have become practically and symbolically entangled in the (re-)production of power in public space, reinforcing political choices and giving them a visual and material presence in society. As such, masking orders have sparked new discussions about the nature of liberla citizenship and the limits of individual freedom.

During lockdown, their use formed part of a wider reduction of civil liberties given up by the public in exchange for the greater protection of human life. As restrictions begin to be lifted across some parts of the globe, however, covering one’s face has now become the trade-off for greater freedom of movement and a return to some semblance of normal life. In countries where face masks have long been associated with certain religious affiliations, with gender inequality, or with criminal intent, publics are now having to learn to view them as compatible -even key- to public life and notions of civility.

References

Blakely, D. 2006. Mass Mediated Disease: A Case Study Analysis of Three Flu Pandemics and Public Health Policy. London: Lexington Books.

Burgess, A. and Horii, M. 2012. Risk, ritual and health responsibilisation: Japan’s ‘safety blanket’ of surgical face mask‐wearing. Sociology of Health & Illness, 34: 1184-1198.

Crosby, A. 2003. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Fox, N. 2011. Boundary Objects, Social meanings and the Success of New Technologies. Sociology, 45(1): 70.85

Horii, M. 2014. Why Do the Japanese Wear Masks? A short historical review. electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies, 14 (2).

Loeb, Lori. 2005. ‘Beating the Flu: Orthdox and Commercial Responces to Influenza in Britain, 1889- 1919’. Social History of Medicine, 18(2): 103-224.

Spooner, John L. 1967. ‘History of surgical face masks: the myths, the masks, and the men and women behind them,’ AORN 5(1), 76-80.

Images:

Featured Photo: Photo (cropped) by Daniel Tafjord on Unsplash

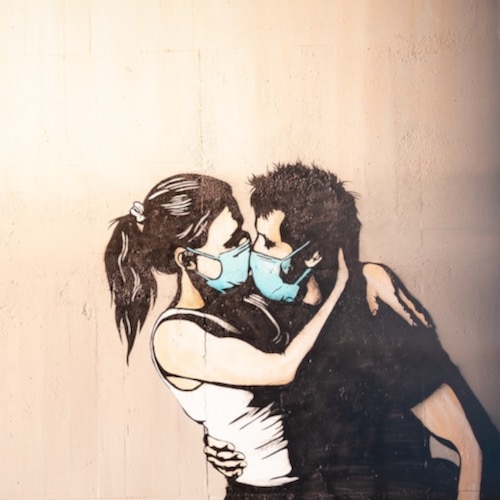

Thank you. Image created by Vanessa Santos. Submitted for United Nations Global Call Out To Creatives – help stop the spread of COVID-19. on Unsplash

Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

Coronavirus screens, Bank Station, London. Photo by Étienne Godiard on Unsplash