Around the world, countries have imposed lockdowns, to varying degrees of severity, in attempts to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Graduate students (and other researchers) have had to leave the field, pause their research, or restructure it to online, physically-distant modes. As a PhD candidate “in the field” in Peruvian Amazonia, I, too, have had to grapple with how I will need to reconsider my research project in light of pandemic restrictions. My Canadian university told students abroad to return home; I received the notice on March 16, the same day Peru’s national lockdown and closed borders took effect. Peru has now been in lockdown for over 90 days. One person at a time may leave their home to buy food, go to the bank, or to the pharmacy. Although originally the lockdown was set to end on March 31, the government has extended it several times – it is now set to end on June 30. (Although some businesses are starting to be allowed to open, in a limited capacity – and honestly, people here can’t afford to be locked in their homes anymore, if they ever could.)

As people in other places are re-gaining mobility, and universities are slowly considering how they will allow in-person research to resume in socially-distant ways, I was forced to grapple with the disjointedness that I’ve felt throughout lockdown. This feeling of disconnect can permeate all of sociocultural anthropological fieldwork – although our research strives to move beyond and learn from these sometimes-awkward moments. But in times of collective trauma, I was forcefully reminded that the current ordeal can exacerbate past suffering.

For me, the fearful murkiness of the unknown has made the air, at times, heavy; my family, my in-laws, and I take turns worrying about all that we do not know about what is happening in the world outside.

Of the terror and violence of the Amazonian rubber boom of the late 1800s (1879-1912), Taussig writes about “the power of epistemic murk in the politics of representations” (1987: 36). The stories of violence, their exaggerations, and the violent acts themselves swirled and enveloped Amazonia with the affective experience of threat. Taussig starts with the rubber boom, but he explores how the murky threat of danger seeps through stories of sickness, death, and healing in Amazonia in his (then) contemporary fieldwork of the 1970s and 1980s. Today, the murky terror in the age of COVID-19 is spread through and alongside conspiracy theories, miracle cures, and news reports of death and dying. Around the world, there are competing stories and explanations of what COVID-19 is, where it came from, and what to do about it. For me, the fearful murkiness of the unknown has made the air, at times, heavy; my family, my in-laws, and I take turns worrying about all that we do not know about what is happening in the world outside.

The fear is amplified by the memory of violent histories. On March 18, the government imposed a curfew (toque de queda). President Vizcarra did not call it a curfew (although the media called it what it was), because he didn’t want to evoke the “bad times of the past”. Instead, he called it “obligatory social immobility.” Regardless of what it was called, the curfew-that-was-not-a-curfew inevitably reminded my in-laws of the darker times they lived through in recent past.

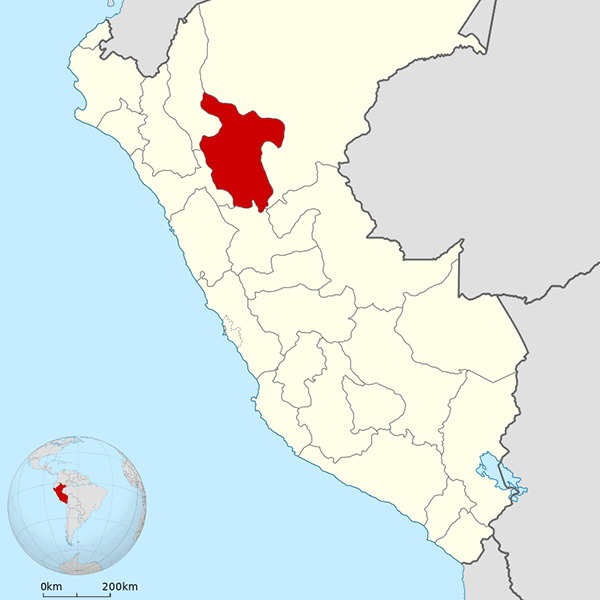

In the 1980s and 1990s, Peru was embroiled in armed conflict. The infamous Shining Path began its uprising in Ayacucho, but the violence spread across the country. Meanwhile, in the region of San Martín, where I am based, coca production was booming. The US estimates 40% of the world’s coca supply in 1990 was grown along the Huallaga watershed (a tributary to the Amazon) in San Martín and Huánuco (Kawell 2005). Coca profits in the Huallaga funded not only the Shining Path, but also the MRTA (Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru), a competing insurgency group with a stronghold in San Martín. These groups fought against one another, and also against state police and military forces. Everyone else was caught in the crossfire. In the immediate aftermath of the Huallaga coca boom, Kernaghan discusses the sense of danger, the “sensorial atmosphere felt by some(one’s) body and a sensibility or affective disposition, but also a direction or good sense that foresees as well as a faculty of judgement or common sense” (2009: 5, original emphasis). The threat of real violence is remembered and held in the bodies of those who lived through the troubled times.

The curfew-that-was-not-a-curfew brought back the sense of danger, filling the air and the body with apprehension. The first few nights, my in-laws reflected on the silence. It was so quiet.

My in-laws, too, have this sense. I notice it in the way the door was barricaded and locked at night, and in other, more subtle cues. The way the body is held, the fleeting expressions of worry. The curfew-that-was-not-a-curfew brought back the sense of danger, filling the air and the body with apprehension. The first few nights, my in-laws reflected on the silence. It was so quiet.

None of the usual busy sounds of the street, of the motorcycles and moto-cars passing by. There wasn’t even any of the loud music that can often be heard coming from one or the other of the neighbour’s houses. Silence, both eerie and peaceful. “Before,” my in-laws tell me, “during the curfew all you could hear were balazos (gunshots).” My partner’s childhood home was made of a double layer of cinderblocks, filled with cement. The inner layer was lengthwise, to help make the wall thicker, in an effort to stop stray bullets. Even with their extra-thick walls, when they could hear the gunfire close-by, they hid under their beds until it subsided, or until morning.

The curfew-that-was-not-a-curfew brought the memories of violence and death to the fore, heightening the murky uncertainties of COVID-19. As I sit in my kitchen in the quiet of the evening, after my young children are asleep, my mother or sister-in-law would come and sit with me, to share the memories that inevitably surfaced: of seeing last night’s victims laid out in the town plaza as a child; of their own close calls with death; of the dangerous game of needing to be friendly with all sides. The most I can do is witness their pain, and listen. The news stories mirror the memories: in Ecuador, Guayaquil’s COVID-19 victims rotting in the streets – their system had been too overwhelmed to collect them. In Brazil, Manaus is building trench graves for their dead. In Peru, in Iquitos, people are turning to the black market to find needed oxygen, where prices are unaffordable and rising (the rising prices of medicinal oxygen also affects other parts of Peru).

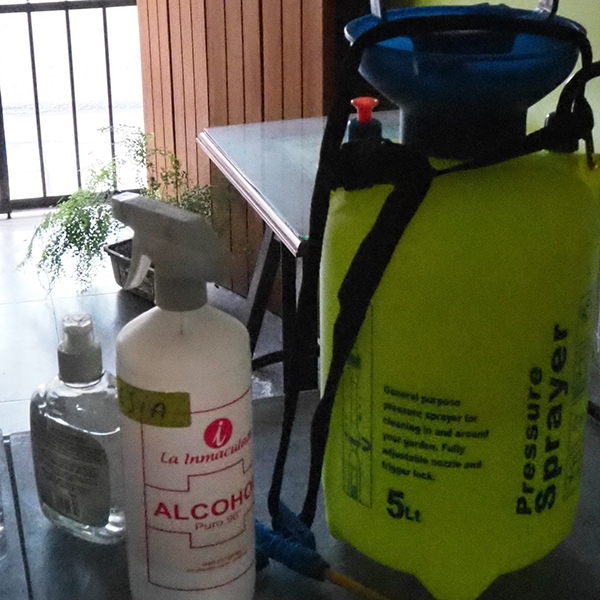

My household implemented a strict protocol for entering the house after going to the market for food (shoes disinfected and off at the door, shower and change clothes, wash everything brought in from outside). These precautions, which may sometimes feel too cautious, come from remembering the real danger of death outside the door, from the sense of threat (Kernaghan 2009).

Meanwhile, friends and family in Europe and in North America are starting to see their restrictions slowly lifted. In Canada, their suggested “shelter-in-place” was largely followed, and largely unenforceable (unlike the lockdown in Peru, which is mandated through legislation and enforced by national police and military). During a recent Zoom meeting, I’ve realised (many, but not all) of my colleagues are finding ways to move their research forward, in some form. I, too, have been reflecting on how I will return to my research – following human-tree relationships across urban and rural spaces – with restricted mobility in a place that has inconsistent access to internet and technology.

Through this crisis, I’ve often considered myself in an enviable position. When COVID-19 was first discovered, named, and eventually declared a pandemic, my doctoral research was already paused because of a parental leave. I can continue to postpone my return to research, giving myself more time to adjust to the changed circumstances of the pandemic. I have the opportunity to reflect – and document – my experience of uncertainty and I have the privilege to wait until some of that uncertainty has had time to settle.

Murkiness continues to breed distrust and suspicion – of the government, of the official numbers, of the capacity for patient care. People are afraid to bring their sick to the hospital, because staff are too busy to keep patients’ families informed and people fear that the sick are brought there to die.

I am thankful I still have that pause button, as life in Peru remains suspended in the murk. Despite taking early action, the lockdown has not worked. In San Martín, we were relatively spared until May, when people began to start leaving their homes more frequently in search of income. The public hospital in Tarapoto, the largest city, is now full, while the designated public COVID hospital remains closed for renovations. Murkiness continues to breed distrust and suspicion – of the government, of the official numbers, of the capacity for patient care. People are afraid to bring their sick to the hospital, because staff are too busy to keep patients’ families informed and people fear that the sick are brought there to die.

Many of those needing critical care are treated at home, and struggle to find oxygen, medicines, and doctors able and willing to do house visits – and the money to pay for it all. Rumours continue to spread, some verifiable, about people dying because of lack of oxygen and about government links with mafia to control the local medicinal oxygen market. While elsewhere people are starting to consider life after lockdown, my family and I have settled into our new reality. South America, according to the WHO, is now the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

References

Kawell, Jo Ann. 2005. “The Cocaine economy.” In The Peru Reader: History, Culture, Politics. 2nd Edition. Edited by Orin Starn, Carlos Iván Degregori, and Robin Kirk. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Pp. 425-437.

Kernaghan, Richard. 2009. Coca’s Gone: Of Might and Right in the Huallaga Post-Boom. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Taussig, Michael. 1987. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. Chicago: The Chicago University Press.