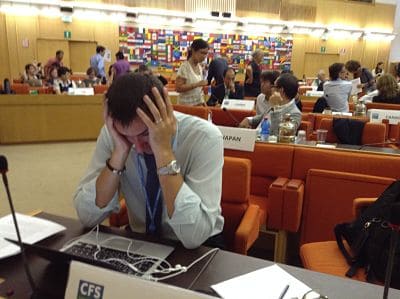

How to govern the “global land rush” was at issue in the final negotiations on Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems at the Committee for World Food Security (CFS) in Rome from the 4th to the 8th of August 2014. For a week, a policy drama unfolded. On stage were private sector organisations clearly supported by the United States, Canada, Japan and Russia who wanted to prevent any regulation of investments. Opposing them were civil society organisations supported by Brazil, Ecuador, the Philippines and to some extent and on particular issues, Indonesia, Pakistan, Egypt, Iran and Sudan who wanted commitments from the governments that they would assume their obligations to govern investments in such a way as to realise the right to food as a national priority. China and India were conspicuously invisible and the EU was unable to hold on to any principled positions. To the disappointment of civil society organisations most Africa countries were ultimately swayed to endorse the US position.

Food producers and land and water users have experienced a long-simmering crisis: over several decades governments (with IMF/World Bank pressure) and corporate markets have undermined or destabilized their production systems, investors and states have seized land, wetlands and forests, and farm/plantation/food workers have suffered declining wages and exploitative working conditions. Altogether, these deteriorating conditions triggered, over the last quarter century, a vast range of struggle, mobilization, and development of alternatives in all regions. By the first decade of the 21st century the crisis came to a head, as financial speculation and monopoly pricing of agro-inputs combined with rising energy costs of industrial foods and use of cropland for agro-fuel production triggered a spike in food prices worldwide.

In June 2008, the Terra Preta Forum, organised by civil society alongside FAO’s Food Summit, noted:

The serious and urgent food and climate crisis are being used by political and economic elites as opportunities to entrench corporate control of world agriculture and the ecological commons.

Crisis conditions provided cover for political and economic elites to impose their will. Transnational and domestic corporate investors, governments, and local elites took control over large quantities of land (and its minerals and water) to produce food, feed, biofuel, and other industrial commodities for the international or domestic markets. The WorldBank entered into an alliance with the G8 and corporate philanthropists like the Gates Foundation, feeding the world the idea that private agricultural investment was the solution to crisis. Conversely, the obvious crisis in multilateral governance also made the reform of the Committee on World Food Security possible. The restructuring of the CFS in 2009 opened up a space for the food insecure populations themselves, among them small producers from all over the world. For the first time in UN history, civil society organisations and private sector organisations were sitting with representatives of governments around the table to discuss and make proposals about food policy issues.

In parallel and behind closed doors, the World Bank, along with IFAD, FAO and UNCTAD crafted Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment (PRAI). Following the rationale of self-regulation of the private sector, the Bank’s PRAI principles do not include any reference to binding legal instruments, for example, national laws and regulations, or international human rights law; rather, they build on corporate social responsibility frameworks such as the Equator Principles, the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), Santiago Principles, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and numerous commodity or theme specific schemes. The Bank’s PRAI principles were never submitted for approval to the governing bodies of the four institutions that advanced them.

At the plenary session of the CFS in October 2010 civil society organisations led the charge to reject the Bank’s PRAI and support a CFS-based process for developing responsible agricultural investment principles (rai), which would recognize the overwhelming role of small-scale producers in feeding the majority world and working the land and the right to food.

Normative framework

However institutional memory is wanting. In May 2014 when the First Draft of the CFS Principles for responsible investment in Agriculture and Food Systems was negotiated after lengthy preparations and consultations all over the world and over the internet the urgencies from hunger riots in the cities and starving rural populations seemed already somewhat forgotten and the First Draft was largely devoid of detail and concrete commitments. The major tension in the CFS deliberations was between a rights based approach defended by civil society organisations that tried to imbue the notion of investment with a moral and normative dimension, and a capital based approach asserted by the private sector, that emphasized that rights based language was the wrong idiom to talk about investments. Quoting the Webster dictionary private sector spokespersons defined investment narrowly as “investing money for profit, the action or processes of capital formation”. The member states of the CFS assumed positions that covered the whole range of positions between these two positions, or rights versus profits.

Whenever civil society suggested “negative” verbs such as “prevent” they were immediately reminded to use positive language. However private sector representatives were also reluctant to include constraining verbs such as “ensure” in the principles that would firmly commit investments to a positive impact. They preferred formulations such as “promote”, “contribute” or “encourage”. It became apparent that many governments, most conspicuously the US, Canada and Russia countered any attempt to introduce words like “regulate” or even “govern”.Proposals to add concrete policy suggestions such as public procurement, public food stocks and distribution were immediately countered by remarks made Canada and the US “to keep it simple, keep it short”.

The distinctiveness of small-scale production

In the negotiation everybody from the private sector and the most liberal of governments to civil society were formally in agreement that investments by “smallholders” were important However, to determine who actually was a smallholder was difficult.The PSM and government allies routinely lumped “smallholders” with “large-holders” as if they practiced the same kind of agriculture, and in the name of “balance”.

This artificial balancing of different “stakeholders” pervaded the CFS dialogue.The PSM and its allies claimed to be simultaneously “pro-poor” and “pro-growth,” and yet “pro-growth’ policies have, by the World Bank’s own admission, regularly discriminated against the poor in the name of “trickle-down” capital growth, prioritizing large investors whose market horizons do not include majority needs. This claim stems from an unproblematic assumption that any increase in investment is positive.

But the pursuit of “capital formation” often implies the progressive transformation of production models to make farmers dependent on purchased inputs: on seeds they are not allowed to reseed, pesticides and herbicides.Outside of the sanitized arena of the FAO’s Red Room, large-scale investments often involve smallholders in out-grower schemes for agricultural investors offering them grower’s contracts for which they carry the entire responsibility if the harvest fails, incurring debts from buying expensive inputs when they cannot reimburse. Accordingly, investment principles apply neither equally nor similarly across this divide. As a spokesperson of the Via Campesina phrased it: “we do not belong to the private sector.”

Civil Society organisations managed to get a clear distinction between farmers that are smallholders and farmers that are private business inscribed in the paragraphs 47 to 50, but the principles fail to clearly differentiate between regulating corporate investment in land and other resources as value capture, and supporting small scale producers and workers as involved in multifunctional livelihood activities – that is, the right to produce food (rather than the right to commodify food). The overwhelming economistic language regarding investment, privileges financial investment and trivializes small producer culture, livelihood and “natural capital”. While the report of the High Level Panel of Experts on smallholder investments recognized “smallholders as the main investors in agriculture” the rai principles undermine that statement by affirming the truism that they are the main investors only in their own agriculture.

For civil society empowering small-scale producers and workers means to consolidate their knowledge and skills in working the land ecologically and harvesting, processing and marketing foods for domestic consumers, and meeting the needs of public procurement schemes for redistribution and emergencies. These are the basics of “food sovereignty” — a term that found no entry into the principles. “Agro-ecological approaches” are mentioned in Principle 6 but only to be followed immediately by an emphasis on “sustainable intensification”, a euphemism created by the biotechnology industry and its allies to promote genetically modified proprietary seeds as a “package of desirable and appropriate technologies” that would offer solutions to climate challenges, cold, heat and excessive moisture and increase nitrogen uptake through “genetic intensification”.Hidden behind the two terms agro-ecology and sustainable intensification, two opposing models for the future of agriculture thus get amalgamated, a corporate led model of high-tech agriculture and a model building on the creativity and ingenuity of small-scale producers supported by participatory agronomic research, as the states, unable to take clear decisions, manouvred in between these two models.

For civil society empowering small-scale producers and workers means to consolidate their knowledge and skills in working the land ecologically and harvesting, processing and marketing foods for domestic consumers, and meeting the needs of public procurement schemes for redistribution and emergencies. These are the basics of “food sovereignty” — a term that found no entry into the principles. “Agro-ecological approaches” are mentioned in Principle 6 but only to be followed immediately by an emphasis on “sustainable intensification”, a euphemism created by the biotechnology industry and its allies to promote genetically modified proprietary seeds as a “package of desirable and appropriate technologies” that would offer solutions to climate challenges, cold, heat and excessive moisture and increase nitrogen uptake through “genetic intensification”.Hidden behind the two terms agro-ecology and sustainable intensification, two opposing models for the future of agriculture thus get amalgamated, a corporate led model of high-tech agriculture and a model building on the creativity and ingenuity of small-scale producers supported by participatory agronomic research, as the states, unable to take clear decisions, manouvred in between these two models.

What Role for the State?

One of the most heated but at the same time diplomatically disguised debates occurred about the inclusion of the imperative “do no harm,” taken from the multilaterally endorsed Ruggie Principles which make business enterprises responsible for protecting and respecting human rights and for providing remedy in case of infringement. These principles endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011were in many respects precursors of the rai principles that stressed States’ human rights obligations when they legislate for business enterprise. As Marc Edelman shows in an earlier focaal blog, discussions are just beginning in Geneva to make these principles compulsory.

In spite of this fact, however, the two major global players, the United-States and China supported by the private sector and Canada, resisted including the “do no harm” principle. As one of the spokespersons of the Private Sector phrased it: “It is up to countries in the plenary to decide whether they would want to adopt such absolutist language.”

The final draft of the principles fails to put strong emphasis on regulating investments. While it pays lip service to governance of investments by States in the public interest, it lacks the mention of any concrete strong measures. Effective public policies proposed by civil society are rephrased as extremely general statements of intent or remain anecdotal and ad hoc.CSM has been able (we think quite successfully) to sway the document, which would otherwise have been a monument to market driven development, in the direction of rights based language. However, the phrase “realization of the right to food in context of national food security” rings empty, as it is never systematically addressed – probably because of (dead) WTO think. The document that appears to be about investment, avoids really tackling it – because the less said the better from the PSM/state perspective. At the next CFS Meeting in October 2014, Civil Society Organisations will not endorse the document, if Canada gets its way of eliminating the “free, prior and informed consent under the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples” (principle 9iv) from the document. However the thorny question is: will they endorse it, if Canada cedes on this point?

Implementation and monitoring by both the states and the CFS are promoted half-heartedly in the principles. The watchdog role is handed over to civil society. As the document states in paragraph 53, civil society organisations “are also encouraged to advocate for the appropriate use of the Principles, serve as drivers for transparency and accountability”. How are they supposed to play that role if the principles themselves have no teeth. Will the CSM get caught up in a hegemonic “land-grab trap” standing in for principles, that trade unions, indigenous peoples and other organisations, consulted all over the world, wanted strong and incisive, and that turned out weak and entirely outside of their control?

This article was originally published in Focaalblog. It is reproduced here with the authorisation of the authors.