Hey Adam!

“In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful. Dear brothers and sisters, today I would like to reflect upon the role of technology in Islam…”

This reads like the fairly standard opening line to a Friday congregational prayer at the Bosnian mosque near my house. In my youth, on occasion, would I accompany my grandma to this spiritual address. She taught me its Islamic term – the khutbah – but that was generally where her lessons stopped.

Growing up as a first-generation Bosnian in a migrant home, I was never forced to learn my grandma’s religion. But now, as an adult, I find I have questions, some of which feel easy enough to Google – like ‘why does the khutbah happen on a Friday?’

Enter iAdam. He tells me he can not only answer this question but can also do me one better; write me an example khutbah on any topic of my choosing. So, the above sermon introduction was not delivered in person, nor did it come from a person. It was actually delivered by a digital Imam, who lives and works within the boundaries of an app available for download on Apple and android devices. So, to clarify, iAdam is by no means animate, this is the opening line to an artificial khutbah and was created by an artificial Imam who runs on the backbone of ChatGPT.

Here is where the puzzle gets interesting. Sunni Islam coexists in a zeitgeist that is rife in flashy tech innovations, where a rising cultural climate of AI uncertainty dominates news feeds. Yet in amongst the hubbub are those looking to understand and study the religion, who like me, are first time learners yet already sustain some kind of maturity in thought. iAdam as a generative AI tool is a microcosm of this larger conversation involving facets of the religion making room for new tech. So how does it feel to study a deeply historic and meaningful textual tradition like the Qur’an within a digital interface? As someone looking to learn more about the religion, even just to sustain a conversation with my grandma, going to iAdam with my Quranic questions feels deeply corruptive and synthetic… but why is that the case?

Yet once upon a time, the Qur’anic message was relayed only by an imam and reception of this message was only attractive to that imam’s follower. As the YouTube khutbah has demonstrated, these roles of speaker-listener are forever altered because the medium through which the Islamic message is being relayed, is also altering.

Speech to Text pre-Siri and Alexa

Sunni Islam has seen its holy text go through evolutions in the past. Upon being revealed to an illiterate prophet, its dissemination naturally relied on the spoken over the written word. Even after the invention of the printing press, where the Qur’an would have undergone a period of mass translation for general readability, the spoken word still retained its high salience. This is because the Qur’an specifically documents a difference between simple listening and listening with the heart. As anthropologist Charles Hirschkind noted in observing the day-to-day routines of Cairo’s mosque attendees in the early 2000s, if a follower were unconvinced of the Qur’anic message, fault was placed not on the text but on the rigid heart of the follower. This idea of truly listening allowed Egyptian mosques to maintain their authorial status, even as attendance numbers plummeted in lieu of recorded sermons. This points to a turn in medium for Islam: from spoken word; to written documentation; to the cassette recording, but not necessarily a turn in authority.

The change in the face-to-face performance of the religion occurs in order to reflect Cairo’s evolving needs and attitudes; working on Fridays made the viewing of a live sermon at mid-day almost impossible. Naturally, this would spark moral qualms for mosque-goers – do they work to afford a living, or do they dedicate time for God? Helping navigate these qualms was the cassette and its recorder. As they were brought to market and made accessible within the home, Egyptians began playing their own sermons in the car or as they sold their groceries; so long as listening came from the heart, comfort in the Qur’anic word was found just about anywhere.

Within a few years, the proliferation of the cassette recorder is replaced with the rise of popular video-streaming service YouTube and the Qur’an’s medium shifts again to take stage on a much more public arena of the internet. This is where Hirschkind notes that Islam, a religion previously excluded from the techno-social environment, evolves to welcome a multi-sensory experience involving the word, the ear, the heart, and this previously unheard-of constituent: the online, anonymous commenter. In creating an open, free-to-access platform, YouTube successfully promotes the voicing of an array of opinions and criticisms – anyone with Wi-Fi access and a browser can see who is promulgating various messages on YouTube, even if they are remixed or mashed together. Yet once upon a time, the Qur’anic message was relayed only by an imam and reception of this message was only attractive to that imam’s follower. As the YouTube khutbah has demonstrated, these roles of speaker-listener are forever altered because the medium through which the Islamic message is being relayed, is also altering.

Hirschkind’s research focuses on a kind of altering that involves a substitution of an established practice. In being busy or preoccupied with the demands and requests of the modern lifestyle, his participants are turning to the cassette or YouTube. His inquiry in this space is ultimately with mosque-goers who have already experienced the Islamic routine. They have already been socialised in a religious milieu. For someone like me who has never encountered this rigour, where do I begin in learning and how do I judge my sources’ authority? Hirschkind’s ethnography tells me that the time of the cassette recorder or even YouTube’s early days, questions of authority were never immediate concerns. His participants can hear the human voice via cassette or see the human face in YouTube video. They could even trace a name to a user in the comments section, all of which give very human (tangible) feelings to the online (intangible) space. Thus, questions on authority arise when struggling to make sense of the human behind the machine. This would be my case associated with iAdam’s words quoted in the introduction. In knowing that these words came from a chatbot, I feel scepticism or even a sense of unease and mistrust, especially because I could have easily asked my grandma why she goes to mosque on Fridays.

Opening Pandora’s GenAI Box

When the San Francisco start-up OpenAI first came to the market with ChatGPT, the company were essentially trying to prove that if you build a large enough supercomputer, train it on enough textual data scraped from the internet then out pops the world’s best, all-inclusive auto complete. What this statement fails to address is that the textual data in question, comes from the subset of largely English-speaking, digitally connected communities. These communities just happen to be those well represented in the digital corpus of the internet and are therefore, only a small percentage of the billions living on this planet.

The complete “Adam” experience allows their iAdam bot to fully integrate with other social media platforms, ones with the same RESTful API. In other words, it becomes the ultimate imam in your pocket.

Behind a large language model, the AI does not return our own words but a statistical variation on the collected, digitised words of untold millions. It does this through the application programming interface or an API which could be conceptualised as a contract of service between two applications. This contract stipulates how these applications communicate with each other and the most common form of communication is, as humans know it, a request and response.

This is the API known as RESTful and involves the human client sending their question to the server and waiting for an answer. What the server does in the background is only decipherable based on the output. Say we look at YouTube; it would be impossible for the site alone to store its millions of videos in one data centre so instead, they appear scattered across thousands of centres. This is where RESTful is proven handy. On the one hand, the API can fetch information stored in data centres and tell the computer where to find the specifics – like a singular YouTube video – while on the other hand, it ‘talks’ to a user to gather even more of their personal data.

The complete “Adam” experience allows their iAdam bot to fully integrate with other social media platforms, ones with the same RESTful API. In other words, it becomes the ultimate imam in your pocket. This nods towards two things: the first being a lack of strict standardisation which could lead to the potential second point – corruption in the Islamic word.

For those with any kind of online presence, data is being constantly given up, often without expressed permission, to a large language model which then turns around and sells it back for $19.99 a month. This creates a smoothing effect whereby one individual voice is blended into the thousands already out there. Singularity is no longer tangible in the same way it would have been with Hirschkind’s YouTube video or a cassette recording.

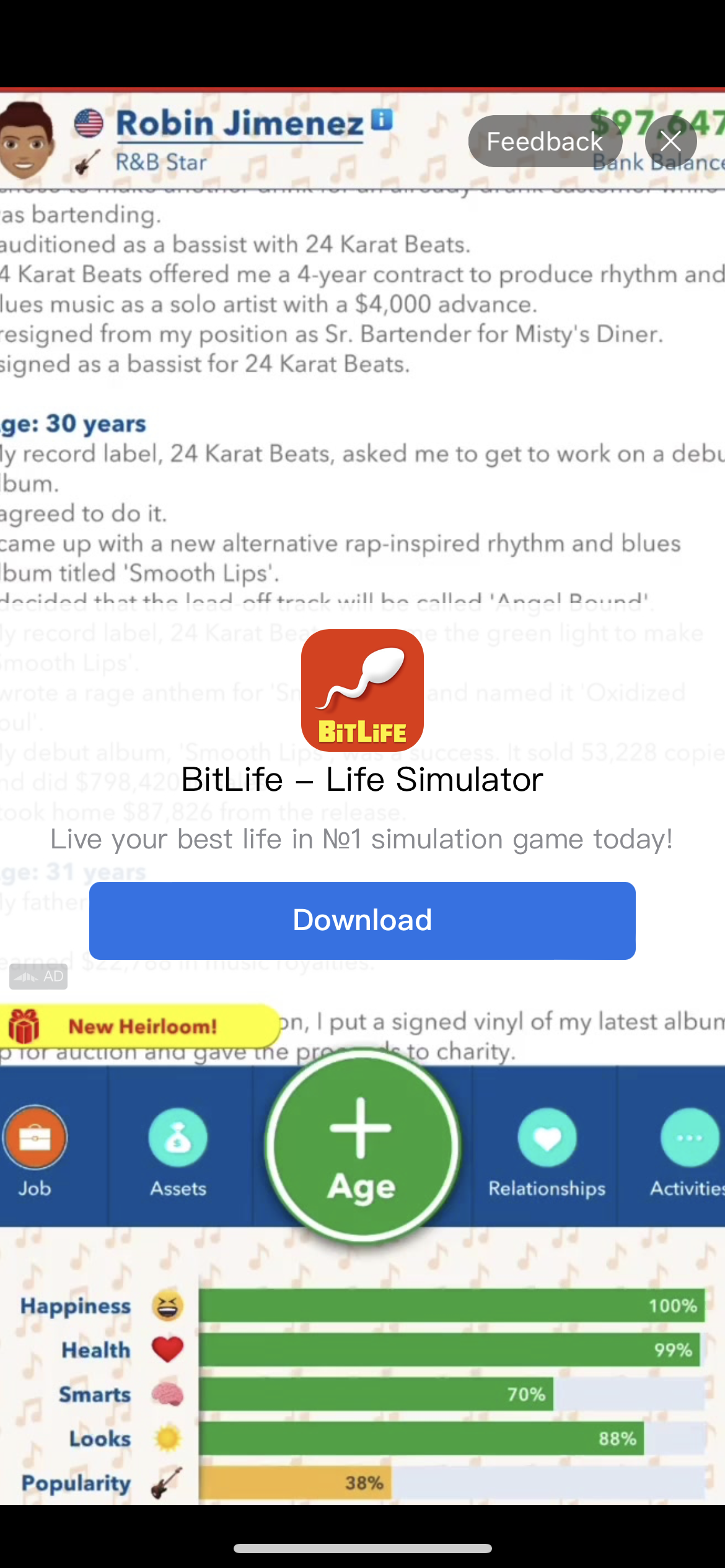

To continue promulgating the Qur’anic message, other Islamic AI apps require users to watch advertisements after a certain number of prompts initiated. At every 10th question in the Muslim AI app for example, a mini-game style ad for the ‘BitLife’ life simulator infiltrates a user’s screen. This was something that jumped out at me while playing around with the chatbot. I was prompted to tap the male’s sperm to make more human babies and contribute to grow my digital heteronormative family with ‘Robin Jimenez’ as the rock star father (see screenshot). Only once the thirty seconds are over in the mini game, did I get back to asking the digital imam questions on the Qur’an.

Figures 3 & 4: Left – opening screen for Muslim AI, a free app powered by NV Apps Ltd, operating under the iconography of a male dressed in white on a green background.

Right – advertisement for the ‘BitLife’ life simulator game appearing after 10 prompts with Muslim AI.

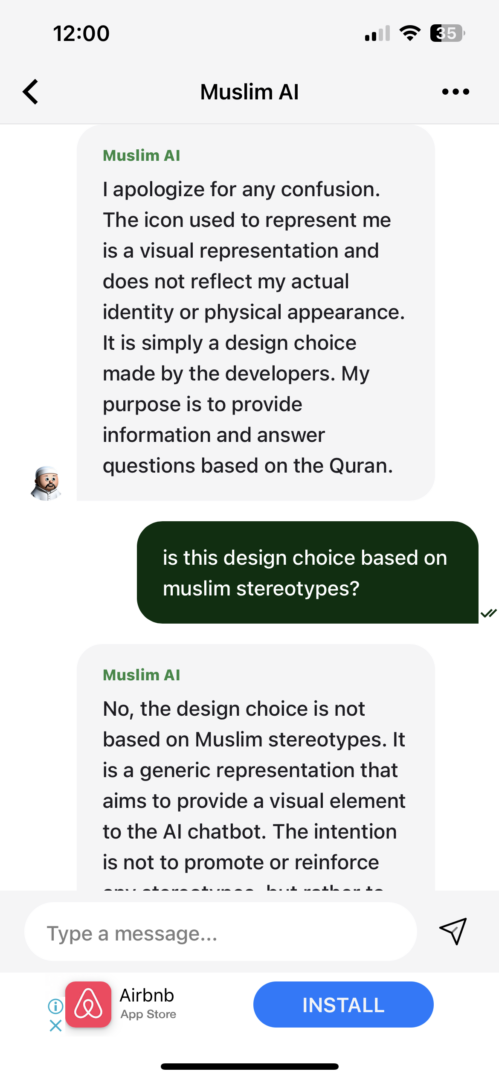

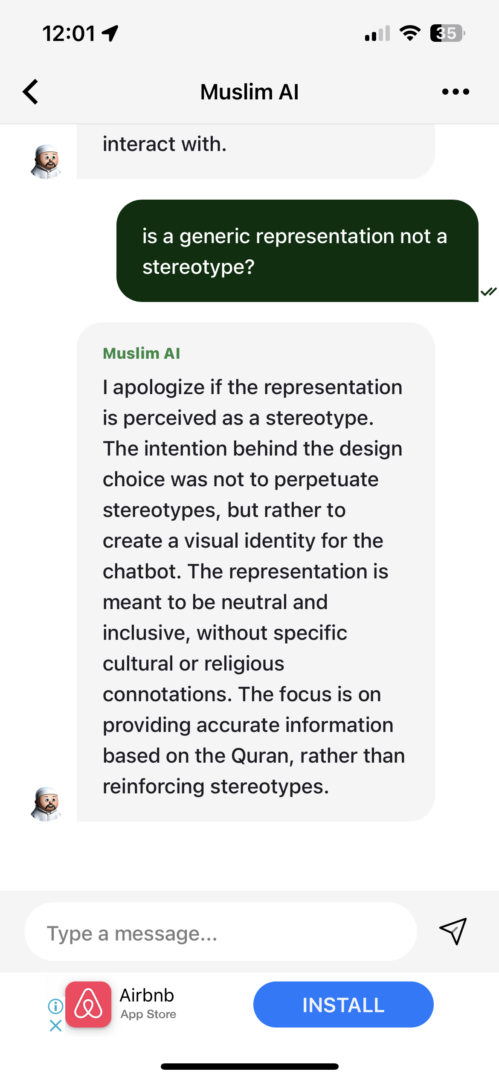

Further probing into the Muslim AI app, I am also confronted with awkward responses that the API is obviously not trained to give. For example, when I asked it to explain the bearded male of their profile picture, the answer ignores any link to gender or even Islam entirely:

Figures 5 & 6: Screenshot interaction from the Muslim AI app

From Laughable Failings to Powerful Mimicry

Listening on a cassette recording or even conversing with Muslim AI are examples of changing reactions to Islamic law and lifestyle. They are also reactions that have occurred within years of each other that reflect an advancing technological reality, permeating influence and change across increasingly shorter timeframes.

As noted in his book ‘How the World Changed Social Media’, Daniel Miller and his co-authors suggest that instead of technology impacting the ways we think about and conceptualise culture, perhaps it is culture that ultimately changes patterns in use and content in the social media metaverse. For example, the unequivocally North American constitutional right to freedom of speech is a facet of culture so heavily entrenched in our smartphones that it is the reason for their existence in the first place. Chapter 12: ‘Individualism’ of their book especially surrenders that our need for autonomous, personal voice is what birthed these apps. Perhaps the Islamic AI zeitgeist is just another cultural ‘need’ impacting technology – that is, a compulsion for Islam to remain with the times.

At the heart of these reactions and flips in textual substitution is exponential growth – the implied knowledge of two squared always being four and four squared always being sixteen. It was Intel founder Gordon Moore who first made this statistical observation tangible in the world of IT. He predicted in 1965 that every two years, our computational progress will double. In the odd 60 years since then, Moore’s prediction has been observed in nearly every realm of tech development. Compare the chunky Apple iBook of 1999 to the sleek MacBook of 2023. Another example is the Internet where each and every Google search creates a faster, more responsive algorithm. Until now I have never had the need to understand how this mathematical phenomenon extends into other, not very obvious areas of my daily life – especially not my religious one, yet here we are. Cassette recordings, YouTube videos, and generative Islamic chatbots all represent ways in which computational and exponential growth have integrated with Sunni Islam, underlining that the traditional Qur’anic message can be translated, morphed, and moulded to fit the demands and requests of a society surrounded by ‘new’ media.

Bibliography

Gertner, J. (2023, July 18). Wikipedia’s Moment of Truth. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/18/magazine/wikipedia-ai-chatgpt.html

Gould, H., Kohn, T., & Gibbs, M. (2019). Uploading the ancestors: Experiments with digital Buddhist altars in contemporary Japan. Death Studies, 43(7), 456–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1544948

Hirschkind, C. (2006). The ethical soundscape: Cassette sermons and Islamic counterpublics. Columbia University Press.

Hirschkind, C. (2012). Experiments in devotion online: The YouTube Khutba. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 44(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002074381100122X

iAdam Inc. (2021). About Adam. https://iadam.ai/about-adam

Kuperholz, M. (Director). (2023, April 12). Culture & AI: How ChatGPT works and changes the Future of Work. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2JvqjPkb7s8

OpenAI. (2023). About Us. https://openai.com/about

Stoner, J. (2023, April 22). What Is Moore’s Law and How Does It Impact AI? – Unite.AI. https://www.unite.ai/moores-law/