On Monday, May 25th, 2020, Cuba’s new president, Miguel Diaz-Canél, involuntarily found himself in the spotlight. Diaz-Canél had become the Cuban head of state two years before, and was widely seen as an uncharismatic successor to Fidel and Raúl Castro. That day, Diaz-Canél made an improvised statement during a meeting with government ministers, which will forever stick to his public image like a red nose. Seated in a leather chair on stage, the president gazed into the air and began to muse. “We have to have lemons in this country,” said the leader. Government officials scribbled notes as he continued, “…Lemonade is the basis of everything. You can enhance any soda with a lemon soda base, and it becomes … a super nice soda, super good! … We no longer have lemons [in Cuba]. We have to look into that.”

To Diaz-Canél’s misfortune, the clip was broadcast as a part of Cuba’s nightly news. Soon, mocking memes began circulating on Facebook and in WhatsApp groups, poking fun at the leader’s sudden nostalgia for a time when lemonade was available across the country. On one level, though, he had a point. Lemons, like other basic food items, had become scarce. (In Cuba, there are seasons not just for avocados and mangos but also “seasons” for toilet paper, matches, eggs, and just about everything else.) However, many Cubans found it twisted to witness Diaz-Canél professing his love for lemonade while vaguely suggesting, “we have to look into” ways of bringing it back. Unlike Cuban government officials, who attribute the island’s shortages to the United States’ economic sanctions, Cubans tend to hold their own leaders accountable for the country’s problems, including the rampant food crisis. Cuba, a Caribbean island close to the equator, imports 70 to 80 percent of its domestic food requirements. Given the Cuban government’s failure to secure basic food production, the president’s longing for lemonade seemed outlandish, even absurd.

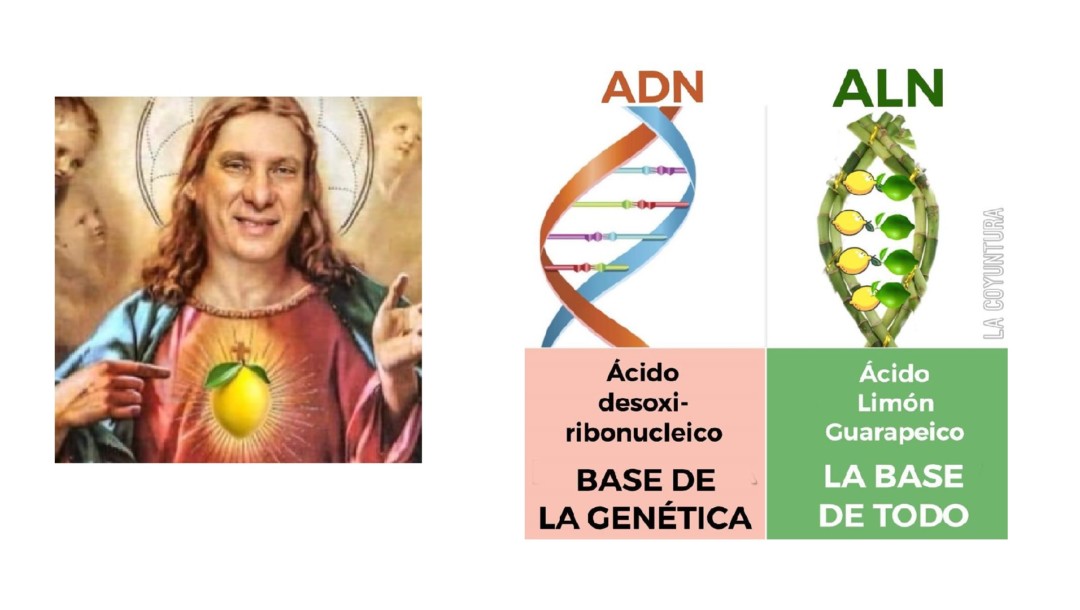

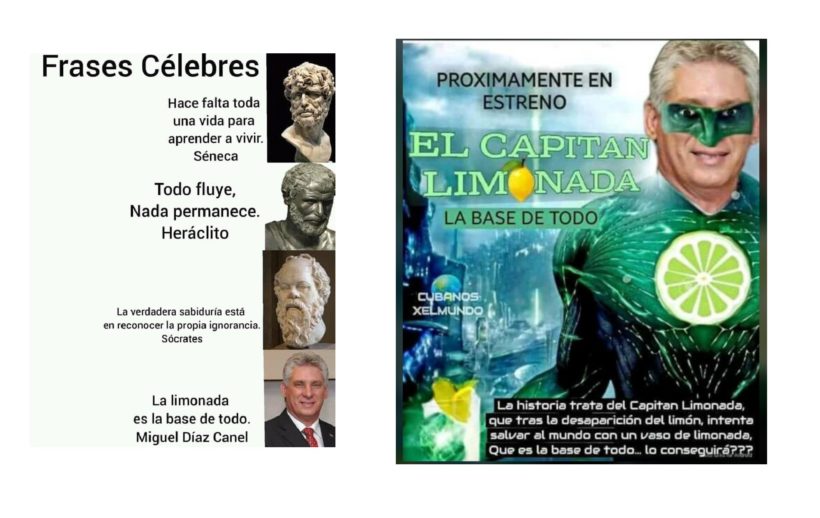

After Diaz-Canél’s reality-defying statements, Cuban humorists wasted no time. One meme juxtaposed the leader’s words, “Lemonade is the basis of everything”, with quotes from ancient Greek philosophers Heraclitus and Socrates. Another showed a DNA model made with limes. A third featured a fictitious movie poster with a new, grey-haired superhero, “Captain Lemonade”, who embarked on a quest to find Cuba’s forgotten lemons. I was in Havana doing field research around this time. At workplaces, bus stops, and around kitchen tables, I heard chatter and jokes about Diaz-Canél and his famed limonada. People recited a new jingle that blended the president’s now-famous words with a reggaeton beat. A satirist uploaded a five-minute video-clip on YouTube of himself asking residents in his neighborhood the same question over and over, “Can you tell me, what is the basis of everything?”

Comedy as epistemology

The spectacle of la limonada would not be the last time Miguel Diaz-Canél provided comedians with cherished material. Yet, this kind of ridicule is far from unique to Cuba. Around the world, political satirists engage in daily races to craft punchlines in response to the statements of politicians, using jokes, memes, or sketches to vie for audience laughter. Clever visuals and wordplay travel far and fast though social media. A memorable example came in February 2022, when the presidents of Russia and France, Vladimir Putin and Emmanuel Macron, met in Moscow to discuss the looming threat of war in Ukraine. With the prospect of another war in Europe in the balance, their somber discussion garnered massive news attention. However, what captivated the global audience was the unusually large white wooden table that kept Putin and Macron apart. It was indeed a curious sight: two world leaders separated by a six-meter-long piece of furniture. Soon, manipulated images began circulating on the internet, mocking the Russian leader’s display of seriousness and power. One image showed Putin and Macron playing tennis on the massive meeting table, while another depicted ice skaters gracefully dancing on its surface. Fake video clips emerged, showing the presidents communicating through megaphones or – my personal favorite – using the table as a seesaw. For a moment, absurdity took center stage in world affairs.

Comedy can serve as a way of understanding the world, especially in settings where people face censorship and self-validating discourse, be it from a Medieval king or a modern-day demagogue. Confronted with authoritarian politics, comedians can become truth-tellers.

Why do these forms of comedy appear to thrive in the realm of politics? What makes them so funny? To answer, it is helpful to recall that politics inherently involves an element of make-believe, which even politicians themselves occasionally acknowledge. During my stint as a journalist in Oslo in 2017, I had the opportunity to accompany Jonas Gahr Støre, the leader of the Norwegian Labor Party and later the Prime Minister of Norway, on the campaign trail. I had written an unauthorized book about Støre a few years earlier (Wig 2014), which may explain his frankness. On one occasion, as we were being driven with armed security to attend a pre-arranged meeting with fishermen in a village in northern Norway, Støre described how the world of politics sometimes felt to him like a “hyperreality”, with its own laws of gravity.

However, not all politicians’ statements are equally ripe for parody. It often seems that the best jokes are cracked in the darkest of times. Arguably, the greatest political parody ever made was Charlie Chaplin’s portrayal of Adolf Hitler as a little dictator, dancing with an inflated globe-shaped balloon. Chaplin’s film was released in 1940, on the eve of the Holocaust. What made Chaplin’s work so brilliant was its ability to show that in all its brutality, fascism is also ridiculous. His comedy reached millions worldwide, exposing the symbolic underpinnings of Nazism while providing, as Mirco Göpfert (2022: 22) describes it, “unparalleled insights into the theatricality of fascism”. Such is the power of the punchline in politics.

Comedy can serve as a way of understanding the world, especially in settings where people face censorship and self-validating discourse, be it from a Medieval king or a modern-day demagogue. Confronted with authoritarian politics, comedians can become truth-tellers. Whether as meme-makers or jokesters on street corners, humorists reveal the inherent absurdity of the political spectacle.

Comedy born of silence

Satire feeds off the sanctity of politics – an atmosphere of gravity and reverence that the punchline subverts. If Hitler had not been so pompous and serious, we would not be laughing at Chaplin’s parody. Something is funny precisely because it upsets the established order. As George Orwell once put it, every joke is a “tiny revolution”, a small attempt at knocking down some authority. “The bigger the fall, the bigger the joke” (Orwell 2002: 781). Sometimes, the smallest of gestures will suffice. In H.C. Andersen’s famous folktale, The Emperor’s New Clothes, it only takes a naïve comment from a child to alert everyone to the awkward fact that yes, the emperor is naked.

Classic late-night satire, such as The Daily Show in the United States, or Striscia la notizia in Italy, seek to create the same effect: reminding viewers of the hollowness of political discourse (Boyer and Yurchak 2010, Molé 2018). Nevertheless, while these are common characteristics of political satire, the social basis for comedy is not the same everywhere. In certain political environments, official propaganda can become so pervasive that people simply stop paying attention to the actual content of what politicians say. Alexei Yurchak (2006) has written about how, during the late Soviet era, “everyone” knew that state-propaganda was hollow. Bureaucrats and party members repeated the same tired Stalinist rhetoric, not primarily because they were afraid to speak the truth, but because the substance of their speech no longer mattered. They were more concerned about echoing the right words than with the content of their speech. Over time, the gap between official discourse and lived reality became a part of what citizens simply took for granted.

This is certainly the case in Cuba, especially among the younger generations who are acutely aware that most of the official discourse in the media is detached from reality. Thus, they tend to ignore it. Occasionally, however, party officials make statements that are so nonsensical that it grabs people’s attention, making them laugh. After all, there is not much else they can do. Leaders like Miguel Diaz-Canél are not only detached from the everyday lives of ordinary citizens but also immune to popular feedback through voting or public debate. Like the Soviet Union, Cuba largely lacks a functioning critical press that can scrutinise leaders. There are no late-night shows on national television to satirise weird statements about lemonade, or other examples of official absurdity. While mockery may thrive in private conversations and semi-anonymous online sites, the national media keeps trotting out the same nonsensical refrain, further adding to the sensation of living in an absurd political culture (see Wig, under review).

Laughing to live

While authoritarian regimes often produce absurd political declarations, these forms of official unreason also extend beyond one-party regimes. We need not look further than to the United States to find political declarations and initiatives that qualify as absurd. Many will remember former US President Donald Trump, who during the COVID-19 pandemic made the astonishing suggestion that people should drink bleach as a remedy. When Trump riffed at a press conference about how scientists should explore the health benefits of injecting bleach, reporters and virologists in the room were forced to listen to his outlandish suggestions, presumably hiding their shock. Trump’s wild advice evokes parallels to H.C. Andersen’s tale of the naked emperor parading through a public square – the unfortunate difference being that, at The White House press conference, there was no child present to call out this emperor’s bullshit. The Trump spectacle also resembles the improvised reflections of Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canél jazzing on about lemonade being “the basis of everything” while directing his party cadres to “look into” this issue. Whether governing an authoritarian state in Havana or presiding over a broken democracy in Washington, these leaders share the privilege of presenting their views uncritically in the public domain. They are little kings surrounded by flatterers and yes-men.

In some cases, however, one can suspect that absurd gestures and statements are part of a leader’s very ideological strategy. The UK’s former prime minister Boris Johnson is a prime example. Known by some observers as “the clown king”, Johnson was an expert in taking the edge off an otherwise ruthless political agenda though hyperbole and ridiculous behavior.

The ability to laugh in the face of power, even when such laughter is cloaked, may be one of few means of resistance for people living under repressive regimes.

Whether resulting from cunning tactics or authoritarian hubris, the good news is that for every megalomaniac emperor out there, there must be a thousand talented comedians and meme-makers. In the case of authoritarian Cuba, critics may hesitate to voice their concerns openly, but private comedy thrives. The ability to laugh in the face of power, even when such laughter is cloaked, may be one of few means of resistance for people living under repressive regimes. While such “tiny revolutions” are unlikely to bring down an authoritarian regime anytime soon, satire and other forms of comedy make it easier for people to understand and live in them. This was often the perspective that my friends in Havana took when the topic of political satire came up in our conversations. Alejandro, a shoe seller I worked with for my research, described Cubans as a species much like dolphins. He delivered the joke while mimicking water rising to his neck, adding, “You know, we laugh, even though we have water up to here.”

Undoubtedly, comedy is more than just a coping mechanism; it is a way of understanding and navigating the world, giving sense and direction to people’s lives. But Alejandro has a point: comedy also offers relief. At the level of everyday survival, we must make the best of a hostile situation. By cracking jokes and drawing smiles, people turn the lemons of authoritarian rulers into lemonade. In a world of naked emperors, perhaps that is the only way to maintain our sanity.

References

Boyer, Dominic, and Alexi Yurchak. 2010. “American stiob: or, what late‐socialist aesthetics of parody reveal about contemporary political culture in the West”. Cultural Anthropology. 25(2): 179-221.

Göpfert, Mirco. 2022. “On dictators and clowns”. Anthropology Today. 38(3): 22-24.

Molé, Nicole. J. 2013. “Trusted puppets, tarnished politicians: Humor and cynicism in Berlusconi’s Italy”. American Ethnologist. Vol. 40(2): 288–299.

Orwell, George. 2002. “Funny, But Not Vulgar”. In Essays. Everyman’s Library; Second Printing edition.

Yurchak, Alexei. 2006. Everything Was Forever, Until it Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. Princeton University Press.

Wig, Ståle. 2014. Seierherren. En uautorisert biografi om Jonas Gahr Støre [The Victor. An unauthorized biography of Jonas Gahr Støre]. Kagge Publisers.

Wig, Ståle. Under review. “States of fear and laughter. On the politics of absurdity in contemporary Cuba”.