On March 18th, 2014 Putin delivered a speech to the Russian Duma where he reclaimed Crimea for Russia. The Russian President did not declare a new Cold War, but he made it known that as far as he was concerned, the post-Soviet order of the past 25 years has come to an end. From now on Russia would be prepared to fight back against any perceived interference in the territories that it considers its sphere of influence, or its blizhneye zarubezhye, the ‘near abroad.’ Implicit in Putin’s statements was the ultimate strategic goal of Russian policy towards Ukraine: to transform it into a protectorate of Russia. On April 7th, pro-Russian protesters seized city administration buildings in Donetsk launching a chain of events which may lead to a repeat of the Crimean scenario in the South-East of Ukraine.

With this much clear, we look back at events in Kyiv, where not long ago Ukrainian citizens came out en masse to protest against the then-Ukrainian government’s decision not to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union. Back then, in November of 2013, many observers in the West were puzzled by the protesters’ apparent enthusiasm for the EU. As Euromaidan swelled and turned into an expression of a desire for wholesale political change in Ukraine, the postulate of EU accession receded into the background but never vanished. On the 21st of March in Brussels, four months after the start of the protests and two days after the annexation of Crimea, Arseniy Yatsenyuk and Herman van Rompuy finally signed the political part of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. On April 10, 2014, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe condemned Russia and showed support to the new government of Ukraine by suspending the voting rights of the Russian delegation. It is difficult to see these acts as anything other than merely symbolic support. From this vantage point we revisit the significance of the ‘Euro’ in Euromaidan.

The notes below are record of a dialogue between the two authors of this post. Both of us do research which touches in various ways on the European Union, its bureaucracy and its borders, as well as on Ukraine, its statehood and its place on the map of Europe. These interests inform our conversation.

KSF: A decade ago, on the eve of Poland’s accession to the European Union, in the Journal of Democracy Adam Michnik published a piece called “What Europe Means for Poland.” The article mixes an idealized view of Europe as the beacon of “freedom, normalcy [and] economic rationality” with notes of bitter caution. Michnik writes: “I will never forget a short story by the Polish writer Ksawery Pruszynski, ‘The Shadow of Georgia.’ The narrator encounters in Paris a minister of the Georgian government-in-exile, who warns him: Do not have confidence in Europe, because Europe will not help you, Europe will betray you. You can count only on yourselves.” Michnik’s essay is a poignant reading today, begging the question what does Europe mean for Ukraine?

LK: This is a paradox. In times when many within the Union question the value and real costs of the EU for people, when some consider leaving this over-bureaucratized ‘unidentified political object,’ people outside the Union, especially in Ukraine, have demonstrated that the idea of united Europe can still hold meaning. More than that, it is powerful enough to mobilize people’s mass demonstrations ‘for’ Europe, something that would be rather odd today within the EU-28.

KSF: Exactly. European integration may be seen as a welcome process in some member states more than in some other ones, but it is hardly the subject of political enthusiasm. So what were the hopes that the protesters in Kyiv attached to the idea of Europe?

LK: First, it is all about long-term alternatives. After the Big Bang enlargement of the EU in 2004-2007 and the ‘fatigue’ that followed, Ukraine had no clear prospects of entering the EU club in any foreseeable future. Simultaneously, another Union – the Eurasian one led by Russia – started to emerge, where Ukraine would be very much welcomed and highly encouraged to join.

KSF: Indeed, Ukraine in the Eurasian Union would be a prized possession. It would move the new Russia-led association pretty far west, up to Eastern boundary of the European Union. It would help assert its power, breathe down the EU’s neck. Not an attractive prospect?

LK: For Western-oriented Ukrainians, the contest between the two Unions represented a rather clear-cut choice: either democracy and (maybe) prosperity alongside wealthy Europe, or a dictatorship and misery under the ‘back in the USSR’ umbrella. For many of them, the European Union is intertwined with the more general notion of ‘Europe’. Europe is a myth of a better life, a dream of democracy and justice, a chance for free movement within the continent, an opportunity to change the country stuck for the last 23 years in post-Soviet limbo. In October of 2013 47% of Ukrainians considered the signing of the Association Agreement with the EU as beneficial for Ukraine compared to 34% supporting the Customs Union with Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. With Euromaidan events evolving the difference in views has modestly changed: in mid-March 2014 52% of Ukrainians were supporting joining the EU whereas 25.6% the Customs Union. In the east of Ukraine, in Donetsk, Luhansk and smaller towns like Sloviansk, there are relatively few active pro-Ukrainian citizens. But the center and south of the country, previously largely undecided in their orientation, are becoming more anti-Russian and more pro-Ukrainian, as shown in recent rallies in Odessa and Mykolaiv.

KSF: All of this is not so different, then, from Michnik’s musings about the meaning of Europe for Poland. The difference is, of course, that back in the early 2000s the political commitment to expand the EU eastwards was firmly in place. Not so anymore.

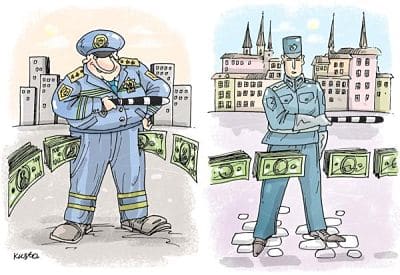

LK: It is true, that the ‘European dream’ is based on images and simplifications than on eye-witnessed reality and economic calculations. The overwhelming majority of Ukrainians (77%) have never been abroad and only 17% of them have ever visited any ‘Western’ country (the EU, the U.S. or Canada), largely because of the ‘Schengen wall’ limiting their mobility. Moreover, political speculations over real ‘costs-benefits’ balance of European integration for ordinary citizens complicate its objective assessment. In September 2013, as part of the campaign supporting the signing of the Association Agreement the World Policy Institute published a series of caricatures. People shared these black-or-white depictions of the West and the East on social media to express support for the Europeanization of Ukraine.

LK: It is true, that the ‘European dream’ is based on images and simplifications than on eye-witnessed reality and economic calculations. The overwhelming majority of Ukrainians (77%) have never been abroad and only 17% of them have ever visited any ‘Western’ country (the EU, the U.S. or Canada), largely because of the ‘Schengen wall’ limiting their mobility. Moreover, political speculations over real ‘costs-benefits’ balance of European integration for ordinary citizens complicate its objective assessment. In September 2013, as part of the campaign supporting the signing of the Association Agreement the World Policy Institute published a series of caricatures. People shared these black-or-white depictions of the West and the East on social media to express support for the Europeanization of Ukraine.

KSF: These cartoons contrast the ‘European’ and ‘the Soviet,’ where the former is neat, plush and orderly, and the latter imposing, corrupt and degrading. The images are quite anachronistic. The West is idealized and the East demonized just like in Cold War propaganda. Has it really come to that? Can’t we think of another way to speak about Ukraine’s perennial place ‘in-between’?

KSF: These cartoons contrast the ‘European’ and ‘the Soviet,’ where the former is neat, plush and orderly, and the latter imposing, corrupt and degrading. The images are quite anachronistic. The West is idealized and the East demonized just like in Cold War propaganda. Has it really come to that? Can’t we think of another way to speak about Ukraine’s perennial place ‘in-between’?

LK: In fact, here ‘the Soviet’ or the demonized side was Ukraine itself as a country drowned in corruption, injustice and inefficiently functioning institutions. The Agreement with its obligations to introduce structural reforms was seen by many people as a turning point. This is why, the sudden U-turn away declared by the Prime Minister Mykola Azarov on November 21st was a shock. People felt disappointed, ignored and deceived. They felt as if their ‘European dream’ was stolen without an explanation or a chance to speak out. People hoped for a ‘a success story’ similar to that of other Eastern European countries which joined the EU ten years ago. That was unacceptable to Putin.

KSF: These tropes of choice between Europe and Russia were current already ten years ago, during the Orange Revolution. But that revolution didn’t deliver, and the disillusionment was powerful. Of course it also didn’t lead to such sharp confrontation with Russia. What was so different this time?

LK: It is all about the new generation born and educated in independent Ukraine which decided that its future in this country is under real threat. The prospects of living for next decades in a society that is falling into authoritarianism, where human rights are not respected and where economy is ruined due to government’s mismanagement and thievery were more than real. Not surprisingly, that students, youth activists and couple of experienced civil society leaders were the first to start a small-scale protest under European and Ukrainian flags with no political affiliation. Their appeals to the President to sign the Association Agreement with the EU and slogans such as ‘Ukraine is Europe’ reflected this ‘European dream’ that seemed to be slipping away. These romantic protests were brought to an end on the night of November 30th, 2013, when students of Euromaidan were beaten by the riot police. The next day, it were their parents who went on streets and the Euromaidan was not primarily about Europe anymore. That however is a different story.

KSF: We shall stay tuned.

Read our previous posts on Ukraine here