Not long after Tufan Al-Aqsa in October, political ecologist Andreas Malm observed in an interview the peculiar temporality of popular revolt in the Arab world. Remarking on the so-called Arab Spring, during which Palestine seemed to experience ‘relative calm’, Malm contrasted it to the current glaciation of popular movements in neighbouring countries as the Palestinian struggle enters perhaps its most decisive moment in recent history. This ‘lack of synchronicity’, says Malm, ‘is one of the biggest tragedies of the Palestine question.’

The non-synchronic and untimely nature of popular revolt has ever vexed the Left in general, and the Western Left in particular. For Lenin, no less, seizing ‘the right moment’ was the decisive, perhaps definitive, act of revolutionary strategy. But workers and peasants have so often moved out of step with history’s forward march; rebels and radicals have either acted too soon, or too late. Time, for better or worse, seems to be ever out of joint.

Time seems also to ever be against us, but never so like now. Amidst total and irreversible ecological collapse on a planetary scale, the abyssal carnage in Gaza portends a future too bleak to fathom, but all too present to ignore. In its impunity and brazen disregard for every principle of legal and human conduct, Israel has enthusiastically plumbed the depths of depravity and barbarism, and in doing so has set new precedents for a global elite anxious to maintain business-as-usual in a dying world. Ever the exemplar for despots and fascists everywhere, the Occupation has, at the very least, demonstrated the Left’s relative powerlessness in the face of highly televised and widely opposed ethnic cleansing and forced displacement. As vast swathes of the planet stand on the precipice of desertification or inundation, and others prepare for extensive and systematic militarisation, the erasure of Gaza threatens to become an object lesson in ‘capitalist catastrophism’.

A new generation of activists has been born, and not just in Egypt.

This perhaps explains the urgency, as well as frustration, with which Left intellectuals issue their reproval of poor timing. Nor is it only the Arab masses who appear to be guilty of the latter. In a more recent essay, for instance, Anton Jäger takes issue with what he calls the ‘hyperpolitics’ of the global Palestine solidarity movement, alongside other recent waves of popular mobilisation, including Black Lives Matter, the gilets jaunes, and, curiously, MAGA republicans. What thematises this unruly selection, according to Jäger, is ‘a form of politicization without clear political consequences.’ If Occupy and the Arab revolts exploded the ‘post-political’ moment at the turn of the century, they seem to have inaugurated a hyperpolitical moment wherein mobilisation is short-term and characterised by ‘low-cost, low-entry, low-duration, and all too often, low value.’ In this way, it is also distinct from the ‘superpolitics’ of formalised, mass membership organisations of a century ago, which are of course the normative standard against which the former are judged here.

This provocation, and the peculiar comparisons it makes possible, is perhaps justified by its concern with temporality. Accordingly, and no more or less than the pairing of BLM and MAGA, its equation between Nazis, Soviets, and Maoists makes sense when we consider their shared temporal imaginaries. Political projects measured in centuries and even millenia sit in stark contrast to a political horizon which appears to mimic the ‘business cycle’ of the market or the lifespan of a viral tweet. The problem is that this is not so much a distinction between different forms of politics as it is between protest movements and their ideological basis. Virtually any wave of revolt can appear ephemeral – ‘as fleeting as market transactions’ – when its historical conditions and antecedents are obscured. The important point is that the market is not a temporal metaphor in this scenario, but rather the main cause of time’s disappearance. The reality of BLM, and Palestine solidarity for that matter, would look a lot less ephemeral were it not primarily consumed through market dominated mediums, social media being the most obvious of these.

Adjusted appropriately, the timescale of Arab revolts would reveal a striking pattern, and one which is instructive for the Left elsewhere. Malm himself, being a student of historical ‘long wave’ theories, might have noted this had he waited a month or two. In Jordan, Yemen, Egypt, and even Syria, revolutionaries have once again taken to the streets in numbers and strength which haven’t been seen in a decade. Since the heady days of the Spring, when ruling autocrats were overthrown within weeks, a brutal counter-revolution has entirely swept away the old movements and coalitions – or so it seemed. It now appears as though a resurgence is at hand, all too ‘synchronous’ with a beleaguered West Bank and a besieged Gaza.

The question of timing and duration assumes a different character when its object is the wider terrain of struggle as a dialectical whole.

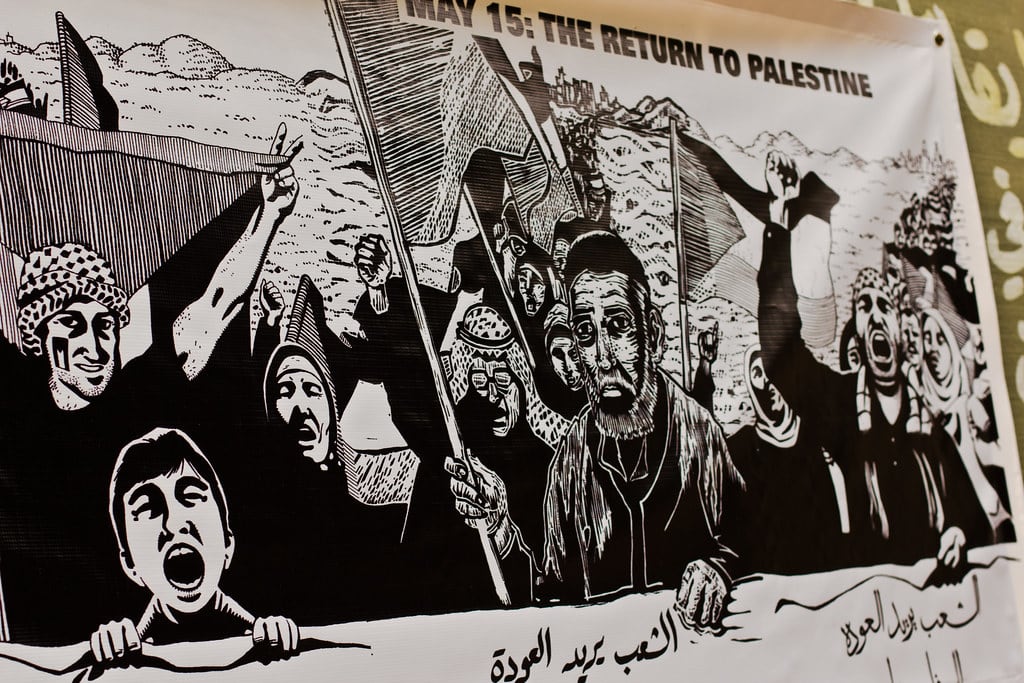

How long and to what extent this resurgence will last (or, namely, withstand state repression) is anyone’s guess, but that’s besides the point here. The question of timing and duration assumes a different character when its object is the wider terrain of struggle as a dialectical whole. From this perspective, the local and regional dimensions of popular revolt are not incidental but rather co-constituted: the former are not just distinct parts of the latter, but in fact bring them into existence. Egypt is certainly exemplary in this regard, though by no means exceptional. The 2011 revolution was helmed by organisations whose main cadres were drawn primarily from earlier movements formed during the Second Intifada and bolstered during the invasion of Iraq. In turn, these coalitions were successors to the last wave of Egyptian communism, itself a beneficiary of anti-Zionism in the wake of the Naksa – or, the Arab world’s 1968. During these successive waves, Palestine was never a mere ideological veneer for the movements, but a condition of their possibility. As Hossam El-Hamalawy recently put it, every new generation of activists in Egypt owes its birth to Palestine.

In this light one may very well ask, as Palestinian scholar Bichara Khader has, whether the Arab Spring itself was actually Palestinian through and through, originating as it arguably did in the First Intifada. Taken seriously, what does this question entail? For starters, and beyond a historicism of origins, it reiterates a basic axiom of radical Arab thought: a liberated Palestine is a precondition of a liberated Mashriq. More specifically though, it also demands that we commit to this struggle on terms adequate and appropriate to its own historical telos. The failure of the Intifada and the Spring to meet in time was a constitutive one, seeing one revolt embrace and carry the promises of the other in a context where victories are short-lived, defeats are long-lasting, and state terror is swift and lethal. That the wider struggle continues to exist at all, and despite all odds, is perhaps a consequence of its supposed ‘non-synchronicity’.

A rendezvous may nevertheless be on the horizon, but in any case, one thing is certain. A new generation of activists has been born, and not just in Egypt. It is everywhere, and while its presence on the streets may seem ephemeral; may ebb and flow, its emergence marks a high point in a historical long wave which will likely transform the terrain of political struggle for decades to come. As in the Arab world, this generation, too, owes its birth to Palestine.