Recently, a series of heated debates around the use and abuse of the buzzword ‘anthropocene’ to qualify our current human epoch have taken place between geologists, environmentalists and anthropologists. According to the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), the professional organization in charge of defining earth’s time scale, we are officially in the Holocene (“entirely recent”) epoch, which began 11,700 years ago after the last major ice age. But that label is outdated, some experts say. They argue for “Anthropocene”—from anthropo, for “man,” and cene, for “new”—because humankind has caused mass extinctions of plant and animal species, polluted the oceans and altered the atmosphere, among other lasting impacts.

For Bruno Latour:

In spite of its pitfalls, the concept of Anthropocene offers a powerful way, if used wisely, to avoid the danger of naturalization while ensuring that the former domain of the social, or that of the “human”, is reconfigured as being the land of the Earthlings or of the Earthbound.(Bruno-latour.fr)

SUSTAINABILITY IN THE AGE OF AUSTERITY – REDUX #economics

By Fiona Murphy

The Four Horsemen, a by now well-known documentary about the global banking crisis, opens with the dramatic statement that ‘we are entering the age of consequence’. In striking intones the opening sequence tells us that the four horsemen are coming, ‘war, conquest, famine and death’. One of the four apocalyptic horsemen that of ecological degradation, while not subject to the same kinds of moral outrage that austerity and the banking crisis have been, nonetheless features large in everyday concerns with the future of the world we live in. Terms like ‘sustainability’, ‘climate change’ and ‘resilience’ have become commonplace, but remain definitionally vague. How we engage with them as citizens, consumers and anthropologists has inflected my recent research on sustainability in Dublin City University.

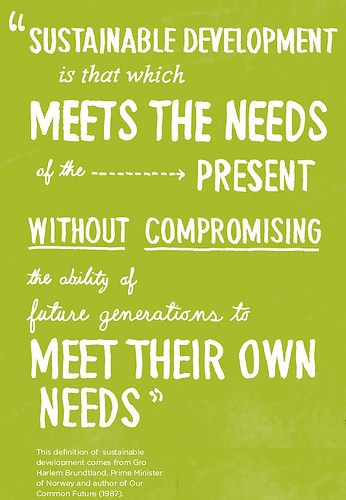

Sustainability, Merle Jacob (1994), points out might well be understood as a ‘metaphysical’ principal with different meanings in differing contexts, its complexity much underscored by varying degrees of contention. The much vaunted Bruntland Commission’s (1987) definition of sustainability as ‘development which meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ remains one of the firmest anchor points in sustainability discourses. Whilst widely cited, it has also been criticized as an attempt to gloss over the role of economic growth and development in ecological collapse. Nonetheless, it began an important conversation, even a new social project, of considering how society might confront the urgency of ecological degradation.

Sustainability, Merle Jacob (1994), points out might well be understood as a ‘metaphysical’ principal with different meanings in differing contexts, its complexity much underscored by varying degrees of contention. The much vaunted Bruntland Commission’s (1987) definition of sustainability as ‘development which meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ remains one of the firmest anchor points in sustainability discourses. Whilst widely cited, it has also been criticized as an attempt to gloss over the role of economic growth and development in ecological collapse. Nonetheless, it began an important conversation, even a new social project, of considering how society might confront the urgency of ecological degradation.

In an academic context, the problematization of sustainability has been engaged with in multi-disciplinary spaces, with research on sustainability taking place in disciplines as diverse as computer science to English literature. Consumption culture and materialism is at the heart of many meditations on sustainability (see Daniel Miller, 2012), especially in an era of widespread anxiety about economic recession. How ordinary consumers might understand the intersectionality of these discourses has been the subject of some of my recent research alongside academics Pierre McDonagh and Sofia Lopez. In an interdisciplinary project examining the impact of austerity on consumption practices and sustainability imaginaries in Ireland, we navigate the existence of multiple ‘sustainabilities,’ thereby mapping a high level of dissonance between how sustainability is imagined, implemented and practiced at different societal levels.

Ireland is a particularly interesting place to conduct this research given the high levels of unemployment, emigration, and crime experienced here during the economic crisis.

It is a country post affluence (the Celtic Tiger) where non-commensurate ideas of prosperity, religion, and politics have ignited deep debate, one which is in danger of characterizing contemporary Ireland’s struggle as a philosophical postscript to the failings of neo-liberal economics. A general sense of disenchantment and malaise is also part of the current zeitgeist, anchored in a broader crisis of faith, identity, and community. In an ‘age of austerity’, Irish society has been subject to widespread fiscal cuts and ‘moral panics,’ even scapegoating of particular segments of society (in particular migrants, ‘single’ parents, the working class). The myth of austerity has, we believe, created new cultural formations wherein notions of the good life, value, and well-being have accrued a revalorized potency. Our work has shown that in spite of a generalized awareness of sustainability at the corporate level (see the interesting Origin Green Initiative by the Irish Food Board-An Bord Bia), the State (A Framework for Sustainable Development, 2008) and amongst ordinary consumers with the visible emergence of a revitalized thrift culture in the shape of second hand shops, flea markets, community garden networks and so on, a unified approach to the implementation of sustainability does not yet exist in Ireland.

While the project of sustainability (if it is to be implemented) can only ever be an interdisciplinary one, working as part of a multidisciplinary project has forced me to further understand the important role that anthropology can play in the development of sustainability science. Given notions of materialism, belief, perception, and values are at the core of the sustainability vision, then anthropology as a discipline is particularly well placed to explore the challenges encountered by the sustainability movement. Further, an applied anthropology can be central to the implementation of many of these ideas. Charles Redman states it as follows:

We all get, as anthropologists, that it takes lots of different ways to understand why people do what they do and what they’re like. The past, the present, the biology, the language—we’ve always understood that a variety of lines of evidence can help enrich our understanding of something. This is a sustainability message too. We can’t just invent a new hybrid car and not worry about who can use it and who can’t. We can’t just put a solar panel on a roof and think that we’ve saved the world. We need to look at it from all different directions and the impacts. Anthropology is a natural for that. In sustainability, what we have to get across is that there are not only multiple lines of information that we need to incorporate, but there are multiple ways of knowing the same information. (Charles Redman, 2011)

Anthropology is producing a large body of work on sustainability and engaging with it in interesting dynamic ways. At last year’s IUAES conference in Manchester, alongside my colleague Pierre McDonagh, we hosted a panel which examined the contributions that anthropological thinking on sustainability are making. The presentations gathered into a forthcoming volume entitled Envisioning Sustainabilities in Times of Disaster (Cambridge Scholars Press, forthcoming 2015) highlight the diversity and impact of anthropological research on sustainability. Anthropologists are working in radically different geographical settings with topics such as community gardens, disaster management in New Orleans, economic crisis in Bulgaria, on community bread-making projects, urban sustainability in Belfast and New York, and in interdisciplinary projects examining topics such as sustainable architecture and urban planning in the UK, and in Bangladesh on water and sanitization projects. Both the depth and breadth of these projects are indicative of a burgeoning and insightful anthropology of sustainability.

In The Expanding World: Towards a Politics of Microspection (2012), Michael Cronin argues that the green agenda cannot be truly envisioned without recourse to ‘a robust sense of social justice’ (2011: 64). In a world where large corporations are building so called sustainable cities through the use of smart technologies, where a small country such as Andorra claims to be the first ‘smart country’, and big data has become the buzziest of buzz words, anthropologists need to be even more concerned with how ordinary individuals understand and glean meaning from these intersecting, often conflicting sustainability discourses. As a discipline wed to a very particular kind of ‘moral optimism’ (Michel Rolph Trouillot), we also need to more fully consider how the application of anthropological understandings of sustainability might very well make an important difference in a world where ecological degradation is now one of our more urgent concerns.