Chimit, a Buryat professional in his late 20s, had been considering moving to Europe for at least a decade, but this plan proved hardly feasible with his low income and thousands of kilometres of distance to cross. Chimit and I had been friends ever since I started fieldwork in Ulan-Ude, in the Russian Republic of Buryatia, a little over seven years previously. In October 2022 we were having lunch in Ulaanbaatar, the vibrant capital of Mongolia. Like thousands of others, Chimit fled Russia to avoid the military call-up for Russia’s war in Ukraine. Having already served in the army, he was a likely draft target, but his family was very close-knit, so the decision to leave was difficult. In fact, it was his parents who eventually made the decision for him. Being used to family life and a fulfilling job, Chimit did not feel well in Ulaanbaatar, where he was sad and lonely, struggling to find work. Just several weeks later, he was back in Buryatia. I heard a variation of Chimit’s story many times over. People’s deep enmeshment in social and kin relations was an important aspect of their courses of action in the difficult and unusual circumstances they were facing. It is these “sticky” relations where tenacious closeness can guide one to war or save their lives – and those of others – that are at the core of this essay.

Buryatia, war, anthropology: Context

On September 21 2022, Vladimir Putin, the Russian President, announced “partial mobilisation” (Rus. chastichnaya mobilizatsiya). Only men up to the age of 50 with prior combat experience were potential draftees to the “special military operation”, as the war in Ukraine is officially called in Russia. Many groups, like those with close family members fighting in Ukraine, or factory workers, were supposed to be exempt from draft. As it turned out, however, the long list of specifications as to who may be drafted was rather meaningless. In places like Buryatia, a multi-ethnic republic in Southeast Siberia bordering Mongolia, the draft turned out to be “tak-to dazhe i voobshche ne chastichnaya” (“actually, not partial at all”), as my interlocutors put it. In Buryatia, many men with no prior military experience were drafted, as were retirees, single fathers, students, and others. Many felt unsafe and left Russia pre-emptively. Queues of up to one day long lined up on the Russia-Mongolia border during the peak of outward migration, while others waited several days to leave Russia via the Russian-Kazakh border.

In places like Buryatia, a multi-ethnic republic in Southeast Siberia bordering Mongolia, the draft turned out to be “tak-to dazhe i voobshche ne chastichnaya” (“actually, not partial at all”), as my interlocutors put it.

I am an anthropologist and have done research in Buryatia since 2015, exploring the post-Soviet Buddhist resurgence. In October 2022, I was in Ulaanbaatar for a pilot research project, looking at how the war is shaping Russia’s ethnic minorities’ lives and identities. Above all, having done research in Buryatia for years, I felt like I owed it to my friends and colleagues in Buryatia to try to understand the difficult position they were in – as well as its broader implications for Russia, Eastern Europe and the world. Buryats appeared simultaneously as perpetrators of Russia’s crimes and its victims, a group disproportionately represented in the Russian army but even more disproportionately represented in discussions about the war, be it in Russian or international outlets and social media. [i]

The motivation for leaving Russia was shared by everyone I talked to – they did not want to take part in the war. The reasons behind this shared motivation, however, varied. Most of my interlocutors did not support Russia’s invasion into Ukraine. Some thought that the situation was “complicated”, but felt that “things had to be solved on a different level.” They mentioned economic sanctions or nuclear intimidation as examples of “how things are done in the 21st century”, rather than open warfare, especially involving a draft of regular citizens. Others mentioned the state of the Russian army as an important factor in their considerations, as the newly mobilised were not provided adequate gear. Yet others wanted to avoid pointless deaths, sensing they would have no control over their own fate in the war zone. I heard of avid supporters of the war fleeing the draft too, reportedly not willing to fight the war themselves but blaming Ukraine for the ‘inconvenience’ caused.

It is not like I did not know the “sociological facts” about why men from Buryatia were joining the Russian army. Buryatia is a relatively poor region with few career prospects or ways to make a dignified living, say, for a head of a family with multiple kids. Due to both the socioeconomic conditions and patriarchal expectations, it is typically men who have to provide the bulk of the family’s income. As a region in Russia’s Far East, bordering Mongolia and with China nearby, military service and contract employment is a normalised job and relatively common. Other factors like the extreme censorship of the public sphere play into the situation too, as there are few alternative voices to the official Russian propaganda. Support for the war and Russian patriotism is widely represented, whereas any critical opinions are quickly silenced.

However, I was still struggling to make sense of the decisions that people in Buryatia were making, especially after mobilisation began. Why would so many choose to go fight in Ukraine after they received a draft notice? Yes, most people early on didn’t know they could decline the notice and only get an administrative fine, but seemingly even if one thought jail was the alternative, it was still a reasonable option compared to risking one’s life in a war one isn’t particularly interested in. Especially so since many were drafted despite not having any military experience. I heard from many personal and media accounts from Buryatia that most locals were not actively supportive of the war, and there was more quiet dissidence or neutrality than one sees from afar.

Relational enmeshment

As an anthropologist, I should have known better than try to comprehend choices individuals make in tumultuous times. It is not like people don’t have a choice as to whether to go to war or not. They do. Otherwise, I would not have met so many Russian citizens in Mongolia. Some of them were all on their own, with little savings, no knowledge of foreign languages and no contacts to rely on, yet they still chose to leave their stable livelihoods behind, refusing to fight a war they did not support. But people don’t make such choices as individuals, reasonably considering all the pros and cons for themselves. They are enmeshed in their social and kin circles, with responsibilities extending far beyond the self as an isolated unit. The pressure, shame, or even perceived judgement is a substantial part of the considerations that go into important decisions.

One of my interlocutors was glad he had happened to install an automated heating system in their house just a few months prior. After he left, his wife had to look after their detached house on her own, while also caring for a newborn and another child. The weather was getting cold and all household chores now lay on the shoulders of the women whose husbands left, including physically demanding ones like heating and maintenance – sometimes without running water. Pressure from wives left alone to look after households was a common reason for men returning to Russia despite the risk of draft. Some bought basic military gear before returning to Russia where they are sold out, just in case.

The pressure, shame, or even perceived judgement is a substantial part of the considerations that go into important decisions.

Badma, a Buryat man in his mid-20s, was a very likely draft target. Not only had he served in the army, he also had recent combat experience. While he managed to flee the country before receiving a draft notice, his family was pressuring him to return to Buryatia and submit to the call-up. Badma had sufficient experience in the army to strongly oppose the war and do his best to avoid going to Ukraine. Many of his former military friends had already died in this war. But his father in particular was insistent on the Russian position and condemned Badma’s fleeing. When I asked Badma how he felt about this family disagreement, he offered a loving smile, saying that his dad was watching too much TV: ‘It’s okay, I’m working on it. He’ll come to understand me. He is a good father after all.’ In our conversation, Badma expressed anxiety over his uncertain future plans, but also hope that familial love and care will overcome political disagreements in the family. Two weeks later, I learnt that Badma was back in Buryatia, having given in to his parents’ pressure.

Familial entanglements can work in different ways. A Buryat man in his late 30s, Dorzhi, had fled his home in Russia several weeks prior, in an attempt to avoid military draft. Our long interview was trying – he insisted that ‘things were complicated’ in Ukraine and that we shouldn’t be ‘asking for it’ in the Baltics, too, with Lithuania’s, my home country’s, ‘aggressive’ policies towards Russia. Dorzhi had supported the war up until very recently. He was never enthusiastic about it, he claimed, but thought that those in power had sufficient reason for launching the offensive, which the population could not know. The media in Russia, too, supplied plentiful arguments supporting the offensive, so there was little reason to doubt the “operation”. In the summer, however, a close relative of Dorzhi’s died in Ukraine. He was a contract soldier, a young man in his early 20s. The grief of losing a family member led him to rethink the need for the war and Russia’s strategies. Many blogs and videos later, he now was certain the war was a crime on both Ukraine and the population of Russia. Many of Dorzhi’s relatives were in the military, so this was a marginal political position in the family.Despite not having openly shared with them his reasons for leaving, he felt the heavy weight of their judgement and pressure. Shame, betrayal and emasculation were common threads in his narrative, as in those of many other men whose relatives felt they had to submit to the draft. Dorzhi had sufficient savings, and the experience of having lost someone close in the war had strongly affected him, so he did not seem likely to return. But it was clear that the judgement and solitude were weighing heavily on him.

Sticky relationships

It is an emblematic anthropological move to highlight interpersonal relations as a key factor in a field where other motivations may appear more dominant: be it in critiquing the homo economicus model in economic transactions or a purely biomedical focus in the process of healing. It seems to me that interpersonal relationships are similarly neglected in discussions of the war in Ukraine, especially as pertains to the Russian side. Remote observers try to empathise with people by putting themselves “in their shoes” – but not “in their relationships”. Many headlines over the months of the war have asked what the Russians ‘think’ and ‘feel’ about the war, how they ‘make sense’ of it or ‘support’ it, and it is easy to imagine individuals undertaking these acts. It is often either bird’s-eye-view of socioeconomic facts and geopolitics, or the fragmented insights of journalists on the move who come to dominate narratives of the lived worlds of Russians, as they become increasingly distant to outside observers.

Remote observers try to empathise with people by putting themselves “in their shoes” – but not “in their relationships”.

I was already struck by the presence of close others in people’s narratives of their fleeing Russia. In one story, a man’s sister convinced him to leave Russia, but his wife made him return. In another, a spouse convinced the man to flee, arguing that he would be of no use to the family if he died at war. Some Buryats have relatives in Mongolia who provide support settling in in Mongolia – an important factor enabling them to flee mobilisation (see also Humphrey 2022). Yet I also heard stories about an interlocutor’s home village in Buryatia that was now split in two opposing “camps”: those whose relatives were at war were fighting those whose relatives had fled.

But the stickiness of relationships became most obvious several weeks after I had left. Chimit and Badma were back in Buryatia due to family pressure. Semyon, a Russian from Buryatia in his late 30s, was back too. In Ulaanbaatar, we had talked for hours about his hopeful plan to migrate westward, ideally to the US, to “learn about how democracy works” before returning to Buryatia one day and contribute to its democratic future. He was missing his daughter and wife, and just getting by in Ulaanbaatar was tough, but there was a spark of hope for a better, if distant, future in his eyes. Semyon had had conflicts with his wife about the war in Ukraine and she did not support his leaving the country, but he was confident she would come around. Two weeks later, he was back in Ulan-Ude.

Relationships can be sticky – especially so in trying times. What previously appeared as a sustaining net of mutual help and care may now lead to family pressure and condemnation – or it may help people flee the draft. As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues, these sticky relations can mean going to war that one does not care much about. The broader implications of this are bleak both for Ukraine and for the future of Russia. They are also dire for Buryatia, as ethnic minorities die disproportionately on the Russian side compared to the Russian majority (Vyushkova & Sherkhonov, forthc.). Understanding the motivations of people at war beyond individuals and ethics is therefore an important task at hand.

All names in the text are pseudonyms.

[i] For a discussion on this overrepresentation in Russian, see “Мы отбиваемся и от Кремля, и от украинцев“, “Как бурят сделали ответственными за войну в Украине“, in English: “The ‘Savage Warriors’ of Siberia: How an ethnic minority in Russia came to be unfairly blamed for the worst war crimes in Ukraine“.

Bibliography

Humphrey, Caroline. 2022. “The Military Call-Up and the Flight of Buryat Men to Mongolia.” Russia.Post, October 10, 2022. (accessed on December 22, 2022).

Vyushkova, Mariya & Sherkhonov, Evgeny. Forthcoming. Russia’s Ethnic Minority Casualties of the 2022 Invasion of Ukraine: A Data Story from the Free Buryatia Foundation. Inner Asia.

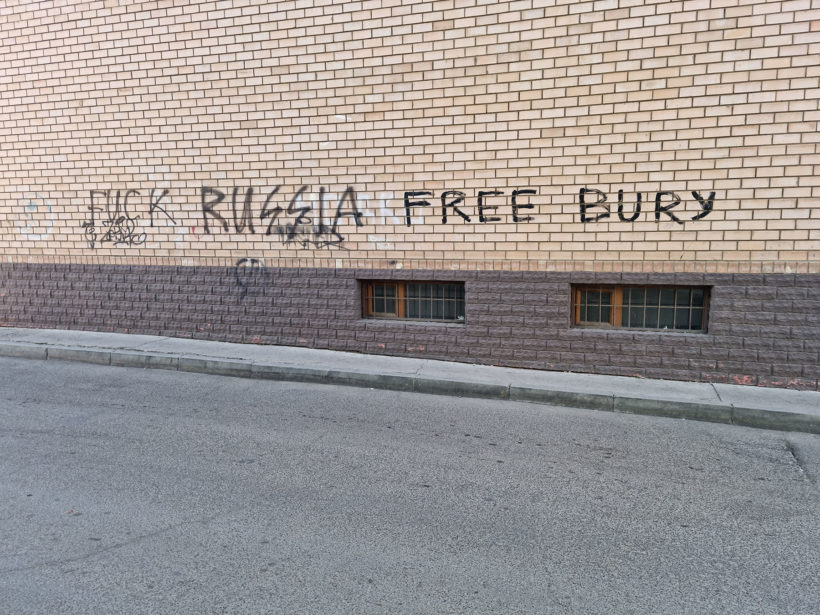

Featured image by the author.